An old French magazine mentions an encrypted message that was found in the estate of a 19th century French soldier. Can a reader decipher this cryptogram?

Prof. Dr. Joachim von zur Gathen, a German cryptologist and crypto book author, recently provided me a page scan from a 1954 issue of a French magazine (I don’t know if the word MARS in the top line of the scan refers to the name of the magazine or to the month March).

A cryptogram from 1834

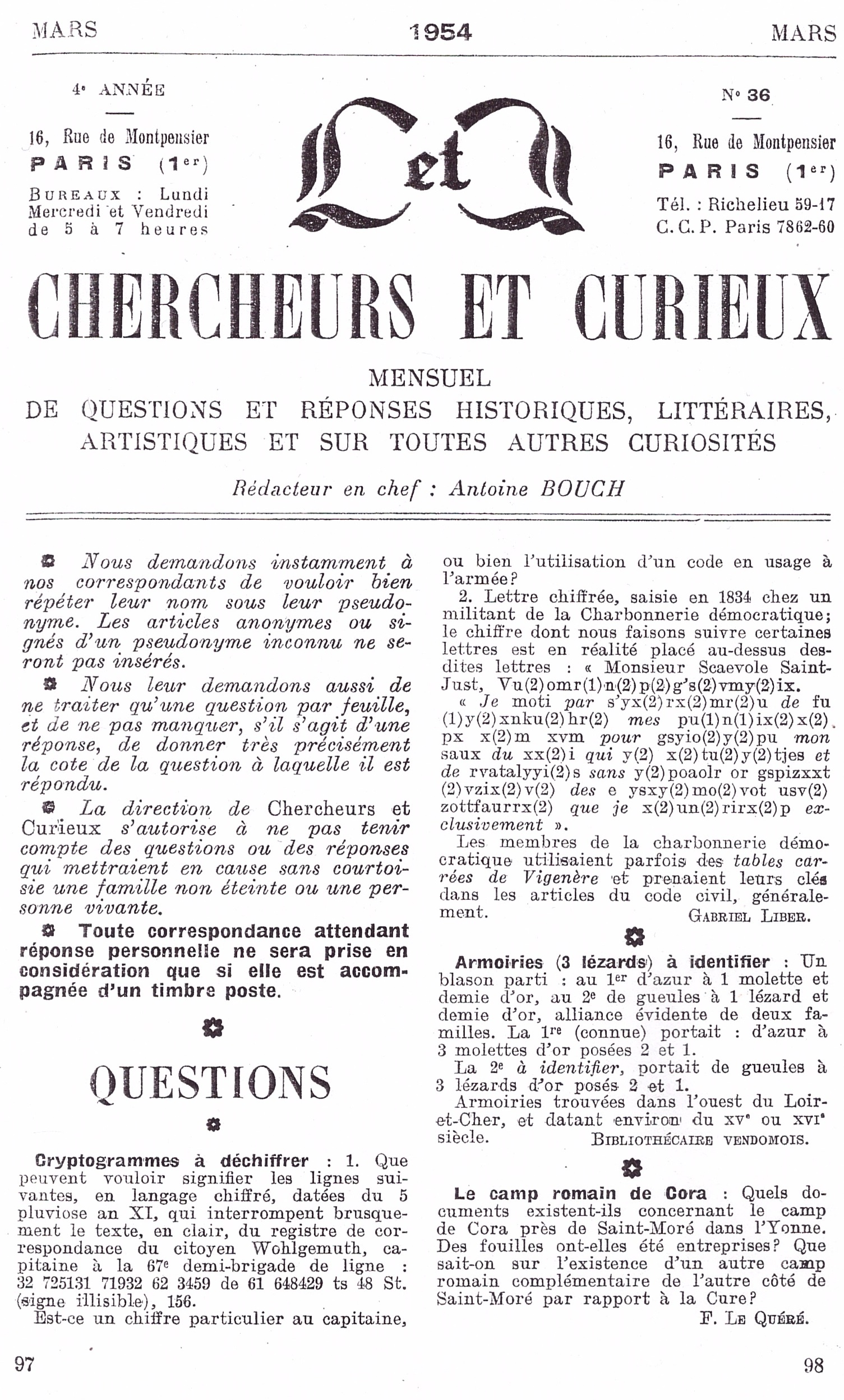

The page in question stems from a magazine column named “Chercheurs et curieux” (“Researchers and Curiousity Seekers”), which covers questions asked by readers. Here’s the scan:

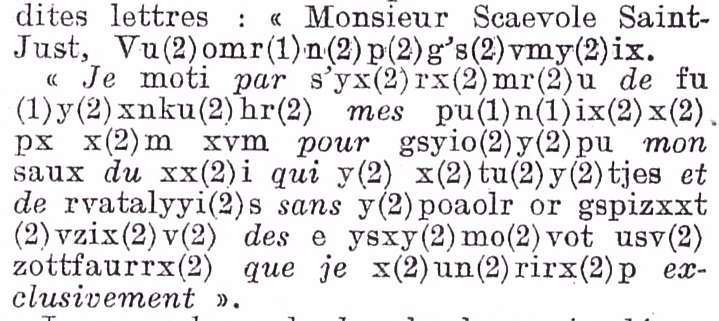

As you see, a reader named Gabriel Liber asks whether somebody can decipher an old encrypted text. This text was found in the estate of a French soldier. It was created in 1834. The following excerpt shows this cryptogram in detail:

As you see, the text contains many French cleartext words (“je”, “qui, “sans”, …), while the rest is encrypted in an unknown cipher. Mr. Liber states that a variant of the Vigenère cipher might have been used. The numbers in brackets might be some key information.

Can a reader break this cryptogram?

A (solved) WW1 cryptogram

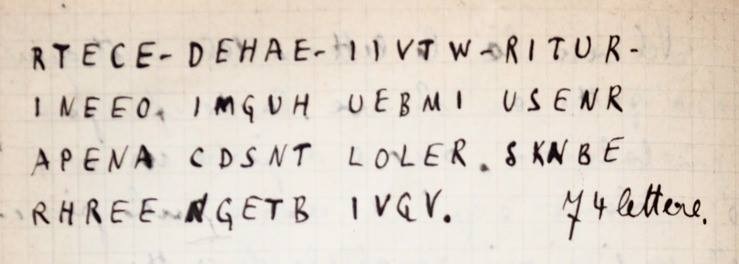

There’s another interesting historical cryptogram that has come to my attention recently. It was published by Paolo Bonavoglia in the Facebook group Cryptograms & Classical Ciphers. Here it is:

This encrypted message stems from World War 1. It was created in October 1916. According to Paolo, the solution is known, but he hasn’t published it yet. So, if you are interested in learning about the solution, you can either try to find it yourself or you should join the Cryptograms & Classical Ciphers group and wait for Paolo to post the solution.

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13501820

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/763282653806483/

Further reading: Who can decrypt this postcard?

Kommentare (4)