Here’s my latest publication: a free brochure about cryptography and codebreaking especially for school children. Thanks to a great graphic artist it looks very professional.

Last year in fall, the German non-profit organisation Stiftung Lesen contacted me. Stiftung Lesen (Reading Foundation) acts as an advocate for reading and media competency in Germany to ensure that every child and adult develops crucial reading and media skills.

One of Stiftung Lesen’s recent projects is a brochure about cryptography and codebreaking for children, connected to the German edition of a book named William Wenton and the Luridium Thief written by Bobbie Peers. Stiftung Lesen hired me to write the text and select the pictures for this brochure, which I consider a great honor. Graphic artist Harald Walitzek did a great job in layouting my input. The result looks absolutely marvelous and very professional. I want to express my thanks to Stiftung Lesen’s Petra Petzhold and Silke Schuster for managing this project.

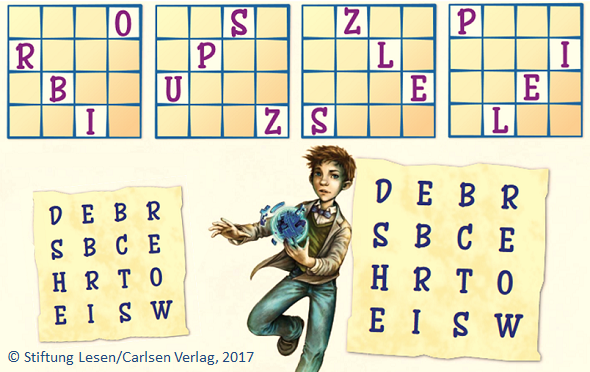

Today the brochure has been published. It can be downloaded for free as a PDF document. Here is a page scan (© Stiftung Lesen/Carlsen Verlag, 2017):

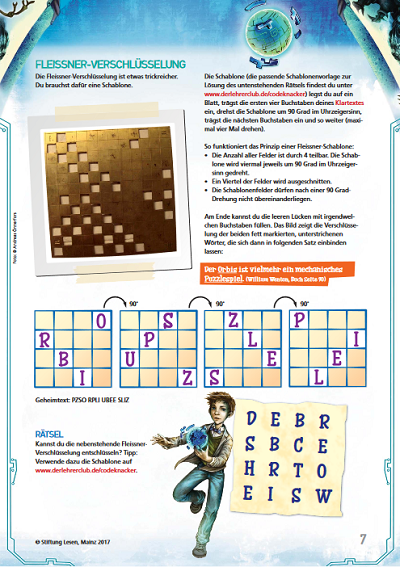

Here’s another one:

The brochure is meant to support teachers to teach cryptography to their pupils. It focusses on classical cryptography, including the Caesar cipher, steganography, the Voynich manuscript and the Enigma. The software CrypTool and the crypto puzzle page Mystery Twister C3 are introduced. Several simple crypto challenges are posed. Frequent readers of Klausis Krypto Kolumne will recognize many of the pictures and cryptograms.

Stiftung Lesen has also started a cryptologic prize puzzle for school classes. The first prize is a class trip to the Deutsches Museum in Munich.

To my regret, this brochure is only available in German. If you can’t read German, you still can try to solve the challenges. The content would certainly be interesting for English-speaking school children, too, but as Stiftung Lesen is a German foundation, no English edition is planned. If anybody is interested in translating the brochure, please contact Petra Petzhold or Silke Schuster.

I hope, many teachers will use this brochure in their classes. I’m sure, many children will love it.

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Further reading: Who can solve these encrypted Christmas cards from the 1920s and 1930s

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13501820

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/763282653806483/

Kommentare (15)