A few weeks ago I introduced two unsolved encrypted letters from the Thirty Years’ War. Scientist and blog reader Thomas Ernst has deciphered them now.

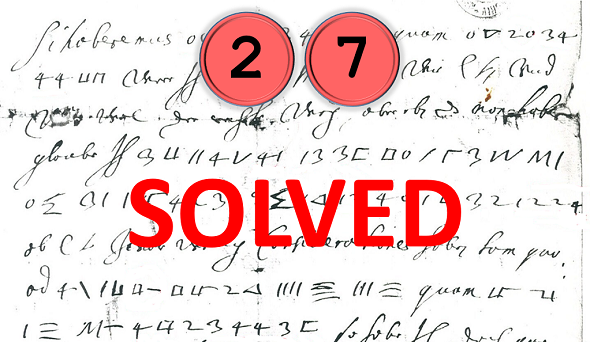

Emperor Ferdinand III (1608-1657) from the house of Habsburg played an important role in the Thirty Years’ War. When researching his life, historians repeatedly encountered encrypted letters. The code consists of numbers and simple geometric symbols arranged in pairs.

In 2014 Prof. Leopold Auer from Vienna told me about these letters. The encrypted passages could not be read. I blogged about these letters and asked my readers to break the code, but to no avail.

Ferdinand’s cipher

In July 2017 I wrote about Ferdinand’s encrypted letters again – as a part of my top 50 unsolved cryptograms series. This time, Prof. Dr. Thomas Ernst, a German scientist who teaches in the USA and is a very active reader of this blog, tried his luck on this mystery. Ernst made a name for himself in the 1990s when he broke the 500-year-old encryption of Johannes Trithemius (1462-1516) in the third book of his Steganographia. This story is covered in my new book Versteckte Botschaften.

In contrast to most other codebreakers, who usually have a computer or engineering background, Ernst is a philologist and historian. He made himself familiar with the world of Ferdinand III very quickly. He also easily learned to read the emperor’s unencrypted letter passages, after the handwriting of Ferdinand III and his use of several languages had created difficulties for many other scholars.

How the cipher was broken

While examining the cipher, Ernst wrote his thoughts as comments below my blog article. Altogether, he posted over 50 comments before the mystery finally was solved. These comments give a fascinating insight into the breaking of a 17th century cipher by a very skilled deciphering expert.

Ernst tested several hypotheses. As an important discovery, he found out that each non-numerical sign represents the number of its lines or semi-circles. For example, four lines stand for the number 4. In one of his many comments Ernst wrote: “From the very beginning, I didn’t like the auxiliary substitution of these signs into letters, as presented early in this thread. It gave me so many false starts! Two days ago, I looked at the signs themselves – again. And there it was, the ‘Eureka-moment’, the same sensation I felt a quarter of a century ago when the numbers of Trithemius’ ‘liber tertius’ unveiled themselves in the flash of a moment. These are good moments: rare, but good!”

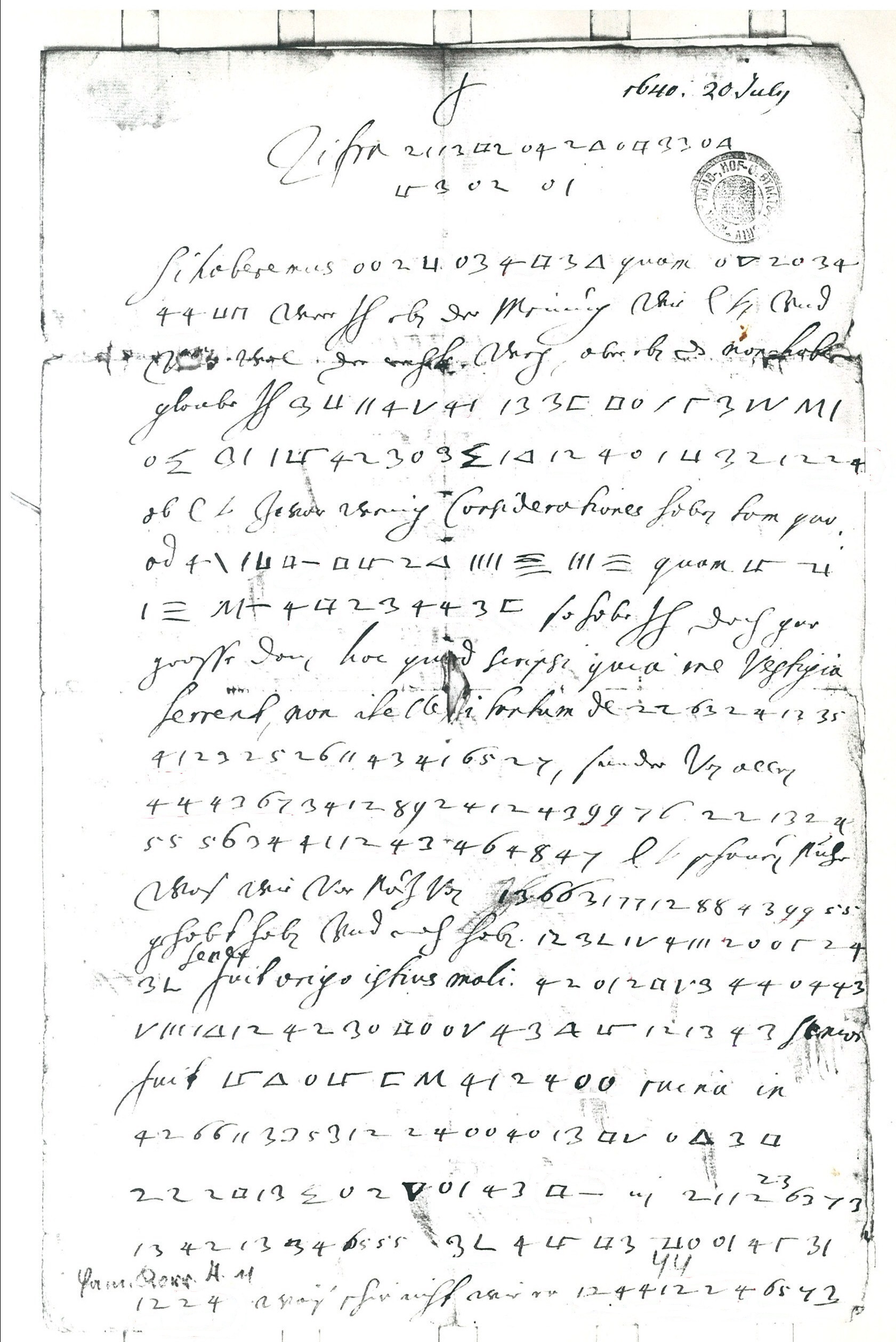

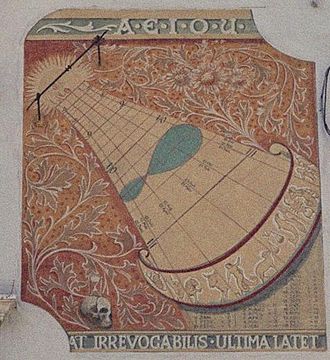

As all non-numerical signs could now be replaced, from now on Ernst had to deal with number pairs only. Based on frequency analysis and probable words, he tried to guess some of the cleartext letters. Another break-through occured when he realised that the Habsburg motto AEIOU played a role in the cipher. AEIOU inscriptions (one out of many interpretations is Austria erit in orbe ultima) can today still be found on some Habsburg buildings, as can be seen on the following picture.

Ernst realised that in Ferdinand’s cipher 01/02 stands for A, 02/12 for E, 03/13 for I, and 04/14 for O – this was derived from the AEIOU motto. When he looked at the phrase “Zifra 21 13 42 04 23 04 33 03 43 02 01” at the start of the letter, he identified the following vowels: “Zifra – I – O – O – I – E A”. The word spelled out here could only be PIC[C]OLOMINEA. As Ernst knew, Piccolomini is the name of a family Ferdinand corresponded with (Piccolominea is the corresponding adjective).

Apparently, the cipher used here was named “Zifra Piccolominea”. Ernst wrote: “The name of the cipher implies that it was also used in correspondence with Piccolomini. My assumption that it was constructed around the Imperial motto AEIOU was correct.”

Next, Ernst guessed the missing word in “fuit 43 04 34 41 24 00 ruina” as NOSTRA. The cipher almost solved now. The remaining letters could be derived easily. Here’s the substitution table:

A: 00, 01, 11

E: 02, 12

I/J: 03, 13

O: 04, 14

10 = Z | 20 = B | 21 = P | 22 = F | 23 = L | 24 = R

30 = K | 31 = H | 32 = G | 33 = M | 34 = S |

40, 41 = T | 42 = C | 43 = N | 44 = U/ V

In one of his comments Ernst wrote: “Terminology-wise, the ‘Zifra Piccolominea’ constitutes neither a code, nor does it contain a nomenclator. It is but a cipher, plain and simple. I am guessing that double consonants were to be enciphered as singles. However, if you follow the letter from 1640, you will notice Ferdinand’s increased laziness in that matter.”

Here’s the cleartext of the first part of the letter shown above, according to Ernst’s decryption:

Zifra PICOLOMINEA

Si haberemus ALIUM quam IPSUM were Ich eben der Meinung wie E L Vnd Were Wol der rehte Weg, aber eben das [na…tes] glaube Ich MAC[H]T IM DESTO HOCHSIEDIGER ob E L Gewar wenig Considerationes haben fore quoad TITULUM quam UITULUM so habe Ich doch gar grosse danen[.] hoc quoad scripsi quia me Vestigia serrent, non rite E Li sortum de F 63 RI 35 TL 2526 ANT 6527, sunder Von allen UN 67 SE 89 REN 9976 FIR 5556 STEN 464847 E L schonen Muhe Was wie Vorstuß Von I 66 H[R] 77 E 88 N 9955 gehabt haben Vnd noch haben. EGENPERG senex fuit origo istius mali. CARL UON LIECHDENSEIN senior fuit NOSTRA ruina in C 66 AM 53 HERADICIS FRIDLANT in PEL 6373 ICIS 6555[.]

An ingenious act of codebreaking

It goes without saying that I am absolutely impressed by Thomas Ernst’s codebreaking work. This is one of the greatest achievements in historical codebreaking I have ever reported on. I am extremely proud, that my blog served as a platform for achieving this success.

Prof. Leopold Auer from Vienna was impressed, too. He wrote: “A very fascinating achievement, which is, of course, of great importance for the history of Ferdinand III” Other readers of my blog posted similar comments.

Thomas Ernst is now planning a publication, in which Ferdinand III’s letters are presented in the clear and the background is explained. Many others letters written in the same cipher by Ferdinand III, his brother Leopold or the Piccolomini family are known to exist. I am sure, it’s going to be a highly interesting publication.

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Further reading: The Top 50 unsolved encrypted messages: 38. The Sufi Fiddle mystery

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13501820

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/763282653806483/

Kommentare (1)