Three months ago, I presented a terminology for codes and nomenclators, based on a workshop that took place at the HistoCrypt conference. After having received some interesting feedback, I can now provide an update.

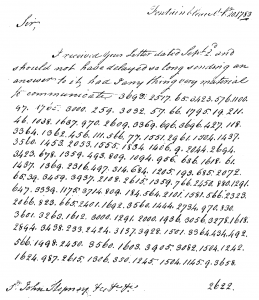

The following cipher message was probably encypted with a nomenclator:

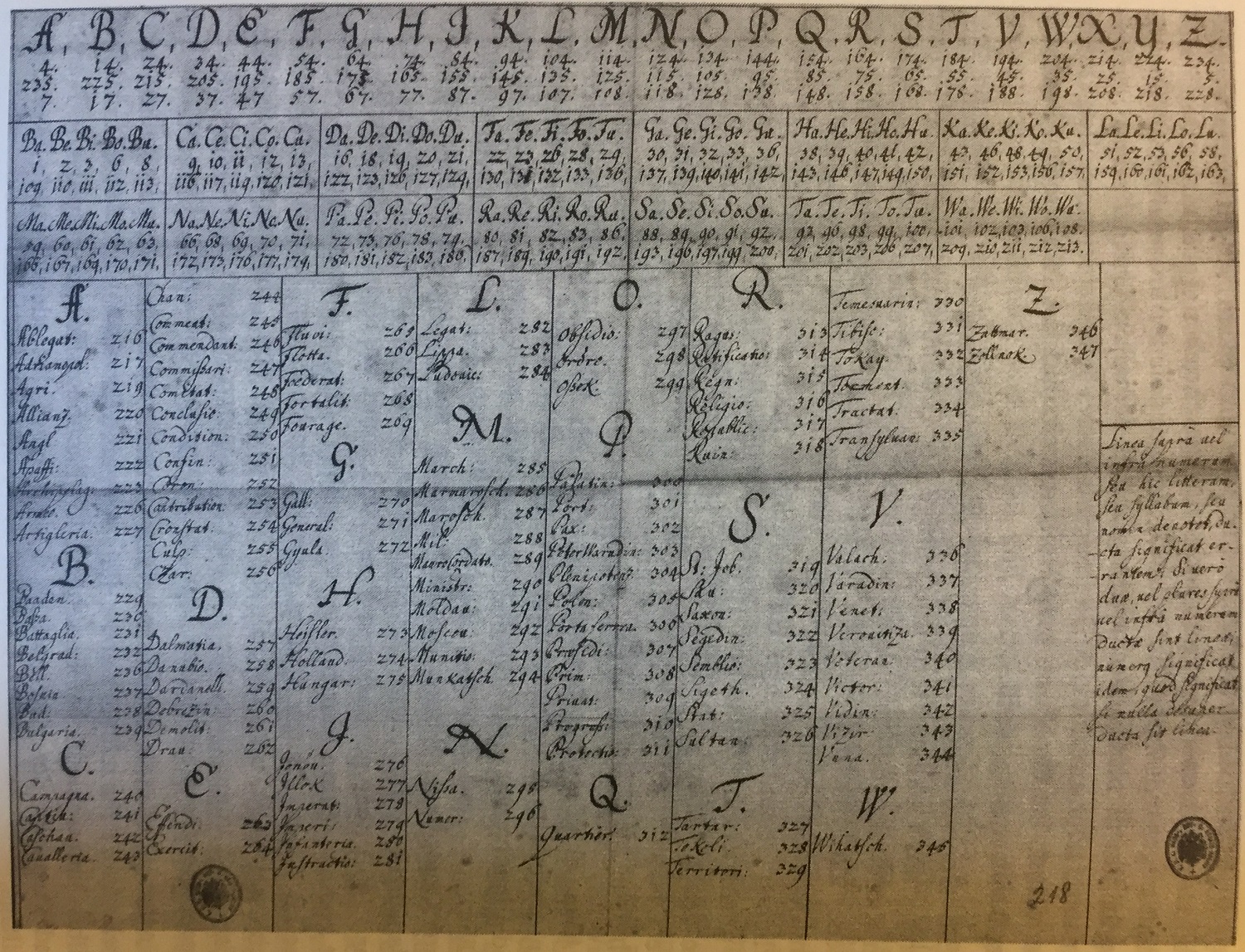

I have introduced this nomenclator message (the Manchester cryptogram from 1783, check here for a transcription) several times on this blog, but nobody has solved it so far. (As Thomas Bosbach pointed out, the letter stems from George Montagu, 4th Duke of Manchester, who in Sept. 1783 not only wrote this letter, but also signed the Treaty of Paris for Great Britain. There is a one-part nomenclator used by his great-grandfather Charles in 1701. Presumably it was a similar system, but with less code groups.)

A nomenclator is an encryption method based on a substitution table that replaces each letter of the alphabet and some frequent words with a number (or another character sequence). The following is a very simple example:

A=1

B=2

C=3

…

Z=26

London=27

Paris=28

Rome=29

today=30

tomorrow=31

Using this nomenclator the plaintext WILL TRAVEL FROM LONDON TO PARIS TOMORROW encrypts to:

23 9 12 12 / 20 18 1 21 5 12 / 6 18 15 13 / 27 / 20 15 / 28 / 31

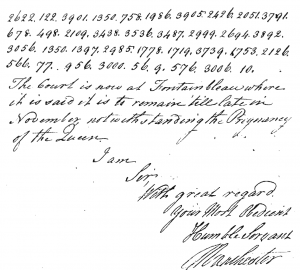

For centuries, nomenclators were by far the most popular encryption method. The following French nomenclator is from the 17th century (it is contained in the paper Briefe durch Feindesland published by Gerhard Kay Birkner in the proceedings of the conference Geheime Post).

In the 18th century nomenclators developped more and more to books (referred to as “codes”) with 50,000 and more entries.

When a code is used, replacing single letters doesn’t play much of a role any more, as for every common word of a language an entry can be found. Codes played a major role in cryptology until the 1930’s, when they were more and more replaced by cipher machines.

Messages encrypted with a nomenclator or code can be found in large number in archives throughout Europe and North America. There must be tens of thousands of them. Only a small fraction has been analyzed so far.

Breaking a nomenclator or code message can be quite difficult. Although cryptograms of this kind are encountered very often, there are only few publications about the systematic breaking of nomenclators and codes. For this reason, Karl de Leeuw …

… invited experts to a workshop about breaking codes and nomenclators at the HistoCrypt in Uppsala. At this workshop I lamented the lack of consistency in the use of terminlogy. There are different, sometimes contradicting definitions of expressions like “code” and “nomenclator”, while other concepts have several names or none at all. As a result of the discussion, I created a terminology I introduced in a blog post earlier this year.

Code and nomenclator terminology

Last change: 2018-10-06

Last change: 2018-10-09 (I replaced “cleartext” with “plaintext”)

Here is a definition of terms related to codes and nomenclators:

- Cipher: encryption method that operates at the level of individual letters (or letter combinations or syllables)

- Code: encryption method that operates at the level of meaning (words and phrases)

- Codebook code: other word for “code” (this term is necessary, as the word “code” has many different meanings, like in “ASCII code” or “postcode”; even in cryptography “code” can mean different things, as the title of David Kahn’s book “The Codebreakers” shows; it therefore makes sense to have an additional word for “code” that can be used for clarification)

- Nomenclator: encryption method that contains elements of both a code and a cipher; this usually means that frequent words, names and locations have their own codegroups, while other words are encoded letter-wise

- Encryption method, encryption algorithm: includes both ciphers and codes (and nomenclators)

- Ciphertext: result of an encryption (cipher or code or nomenclator); (this expression is not consistent, but there is no better word)

- Codebook: book in which a code is noted

- Codegroup: letter/symbol/number or group of letters/symbols/numbers that stands for a word/syllable/expression

- Plaintext unit: word, letter, syllable, or phrase a code replaces with a codegroup

- Wordgroup: codegroup that refers to a word

- Lettergroup: codegroup that refers to a letter

- Syllablegroup: codegroup that refers to a syllable

- Phrasegroup: codegroup that refers to a phrase

- Null: codegroup that has no meaning

- Homophones: different codegroups that have the same meaning (by definition there are always at least two homophones)

- Polyphone: a codegroup that has several meanings (e.g., the singular and the plural of a word)

- Nullifier: codegroup that makes another codegroup meaningless

- Prefix nullifier / postfix nullifier / embraced nullifier / embracing nullifier: nullifier that makes the following / the previous / both / the embraced code group(s) meaningless; expressions like “3-prefix nullifier”, “2-postfix nullifier”, or “2-3-embraced nullifier” may be used if several code groups are made meaningless

- One-part code: code, in which the plaintext units and the codegroups are sorted analogously (e.g., A=1, AM=2, AND=3, ARMY=4, AT=5, …)

- Two-part code: code, in which the plaintext units and the codegroups are not sorted analogously (e.g. A=1523, AM=912, AND=2303, ARMY=809, AT=1825, …)

- One-part / two-part nomenclator: nomenclator, in which the plaintext units and the codegroups are sorted analogously / not analogously

Questions and remarks

Some readers asked questions or left comments:

- The expressions “homophone” and “polyphone” are confusing, as they mean “same sound” or “many sound(s)”.

- Do you have a suggestion for a name for nomenclators that represent 2, 3 or 4 lettered parts?

- What would you call the 4-, 5-, or 6-character blocks that often divide ciphers?

- For transmission, ciphers might have added headers or footers in another cipher or code or plaintext. The composite can be thought of as a “transmission” when it is sent. The word could apply to a bare cipher, as well.

The terminology discussion needs to go on

I hope, this article will help to create a consistent terminology for codes and nomenclators. If you have ideas on how to improve this second version (including answers to the questions asked above), please let me know.

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Further reading: Who can break this enciphered letter written by Albrecht von Wallenstein?

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13501820

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/763282653806483/

Kommentare (1)