Nathan Allen from Maryland died from a bomb that exploded in his car. The murderer was found with the help of a steganographic technique.

On May 10, 1979, at about 10 pm, 45-year-old Nathan Allen got into his car at the end of his shift in a steel factory in Maryland.

Shortly after he had started the engine, a bomb in his car exploded. Allen died, his front-seat passenger was injured.

My talk at the HAM Radio

The Nathan Allen murder case is interesting for encryption enthusiasts because it was solved with steganography (i.e., the science of hidden messages). This is the reason why I included this story in my latest book Versteckte Botschaften, which covers the history of steganography.

On Friday this week, I will cover the Nathan Allen murder in a presentation I will give at the HAM Radio, a radio amateur exhibition taking place in Friedrichshafen , Germany. If you plan to attend this event (I know that there are many radio amateurs among my blog readers), you might want to meet me at the Enigma booth operated by US professor and Enigma expert Tom Perera.

Tom Perera’s presentation slot, which includes my steganography talk, will start at 1600. As it seems, I will also give a second presentation as a substitute for a talk that has been canceled.

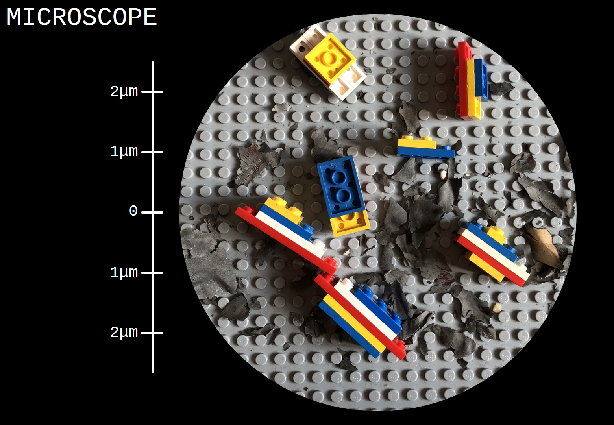

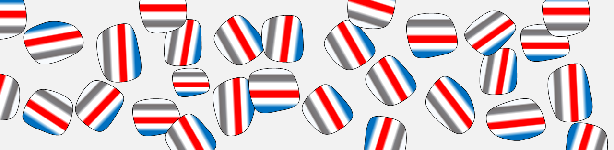

As I couldn’t find many pictures of the Nathan Allen case, I decided to create a few myself. For this purpose, I used a method that has proven quite successful in the past – I built Lego brick models and took photographs of them. In this blog post, I am publishing these pictures for the first time. So, here is my report on the Nathan Allen murder illustrated with Lego scenes.

The Allen case

After Nathan Allen had been killed by a bomb placed in his car in 1979, the police was quite clueless about the murderer.

However, when a forensics expert looked at crime scene traces under the microscope, he discovered something very interesting. He saw thousands of micrometer-sized plastic grains consisting of layers of different thickness and color.

The expert immediately recognized, that he had discovered so-called microtaggants. Each color layer of a microtaggant encodes a letter or a number. In this case, the character string encoded was 8DEO2A146.

The purpose of microtaggants is to make explosives or other materials identifiable. In the case of Nathan Allen, this worked surprisingly well.

Using the identification string 8DEO2A146, the forensics expert could easily determine that the explosive used was of the brand Tovex 220, produced by DuPont. As every batch had a different identification string, the manufacturer could even see in its records that the explosive in question had been manufactured at the Martinsburg (West Virginia) plant on December 2, 1978. A part of this batch went to a retailer named Lawrence Jenkins, also based in Martinsburg. As required by law, Jenkins had noted the names and addresses of his explosive customers. It turned out that his list included a certain James McFillin, who was the uncle of the murder victim.

After having McFillin identified as the prime suspect, Police had little trouble to solve the murder case. McFillin was convicted and sentenced to life in prison.

Microtaggants

From a cryptologist’s point of view, microtaggants are an example of steganography. The police were very lucky to find microtaggants in the explosive that killed Allen – this technology was only applied as a part of a pilot project at the time. Only about one percent of the civil explosives sold on the US market in the late 1970s contained microtaggants.

Despite this success, microtaggants have never become a standard. Only in Switzerland are they mandatory today. In other countries, regulations of this kind were waived because the effort of including microtaggants in explosives was considered too great compared to the benefit (of course, lobbying by the manufacturers played an important role).

Nevertheless, microtaggants and similar technologies are still in use. Several vendors are on the market, having names like Secutag or Microtrace. Microtaggants can be used for a large variety of materials, including explosives, ammunition, metal, plastic, ink, and paint. In addition to solving murders, microtaggants are used to fight fraud and product piracy.

Microtaggants once again show that steganographic techniques are of use in many different areas. Nevertheless, many who use steganography do not even know what steganography is. If you want to know more about this fascinating technique, read my book Versteckte Botschaften. Or come to my presentation on Friday.

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Further reading: Masked Man reveals his passwords after five years

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13501820

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/763282653806483/

Letzte Kommentare