Auf diesem Blog habe ich schon mehrfach das ICCH-Forum erwähnt. Dort gibt es alle zwei Wochen samstags um 18 Uhr einen (auf Englisch gehaltenen) Vortrag zu einem Thema der Krypto-Geschichte, der per Webex übertragen wird.

Ich habe selbst schon mehrfach im ICCH-Forum vorgetragen, teilweise zusammen mit Elonka Dunin, der Ko-Autorin meines aktuellen Buchs Codebreaking: A Practical Guide. In den nächsten Wochen gibt es folgende Vorträge:

- 23. Januar 2021: Tom and Dan Perera: The Disassembly, Restoration and Reassembly of a 3-rotor Enigma

- 6. Februar 2021: George Lasry: The Vatican Ciphers

- 20. Februar 2021: Chris Christensen: A general introduction to Japanese cipher machines

- 6. März 2021: Bill Briere: Constructing Recreational Cryptograms

- 20. März 2021: Klaus Schmeh and Jerry McCarthy: The Zschweigert Cryptograph

- 3. April 2021: OPEN MEETING

- 17. April: tbd

- 1. Mai 2021: Bill Briere: Good Vibrations: Surf, Sex, and Spies

Den nächsten Vortrag gibt es also übermorgen. Ich habe meinen nächsten Auftritt am 20. März zusammen mit Jerry McCarthy.

Demnächst soll es eine ICCH-Webseite geben. Die Teilnahme-Links werden aus Sicherheitsgründen bisher nicht im Internet veröffentlicht, was sich aber ändern soll. Jeder ist zu den Vorträgen willkommen, und die Teilnahme ist kostenlos. Wer dabei sein will, kann mir gerne eine Mail schicken.

Patrick Hayes

Über das ICCH-Forum habe ich letztes Jahr Patrick Hayes …

… kennen gelernt. Patrick, der eine interessante Webseite zum Thema Verschlüsselungsmaschinen betreibt, hat mir folgendes über sich mitgeteilt:

Patrick Hayes is a specialist and collector of cryptologic artefacts. He also brokers cryptologic artefacts linked to the Enigma, T-52 Geheimschreiber and other cipher machines to museums, dealers and collectors across Europe and North America. He is director of the Chiffriermaschine Museum, a virtual crypto history museum available at www.chiffriermaschine.com and is a member of the International Conference of Cryptologic History (ICCH). He is also currently studying History at Durham University, in the UK.

Ein weiteres D-Day-Kryptogramm

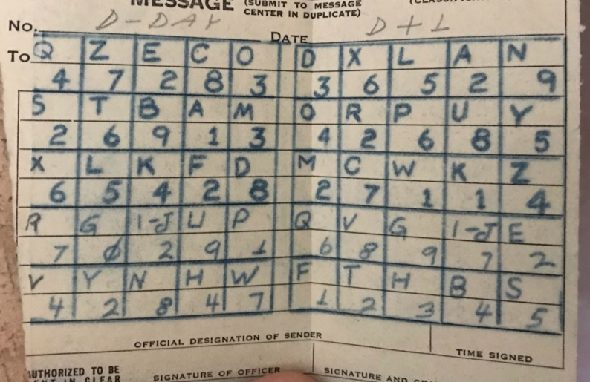

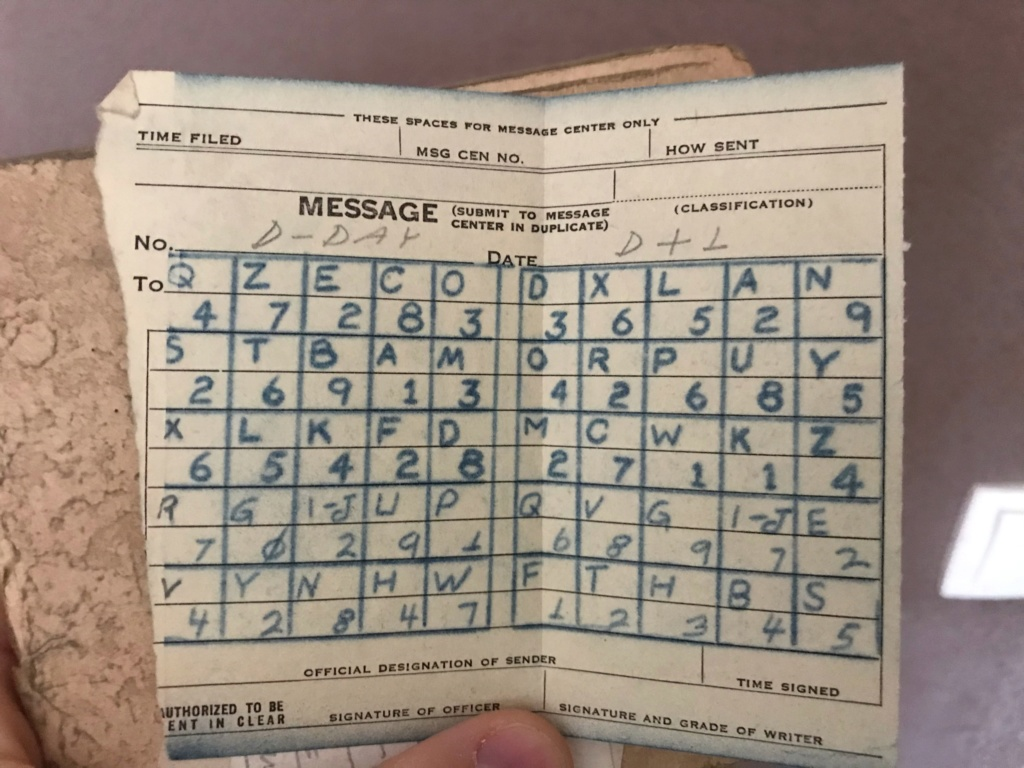

Patrick hat mir vor ein paar Tagen einen verschlüsselten Text aus dem Zweiten Weltkrieg zugeschickt:

Die Aufschrift “D-Day” deutet darauf hin, dass diese Nachricht etwas mit dem 6. Juni 1944, dem D-Day, zu tun hat. Leser dieses Blogs werden sich vielleicht daran erinnern, dass es bereits ein bekanntes ungelöstes Krypto-Rätsel gibt, das mit diesem Tag verbunden ist: das Brieftauben-Kryptogramm.

Leider ist über den Hintergrund dieser zweiten D-Day-Nachricht kaum etwas bekannt. Patrick hat mir folgendes dazu geschrieben:

The message paper is probably from a M-210-A message pad and is in five letter groups. Unusually, the words “D-Day” are written on the form and the writing on the message form is in cipher, rather than the usual transcribed clear. The date looks like “D+L”, but I think it may perhaps be “D+1” (D-Day + 1), a term used by the Allied forces for the day after D-Day. The rest of the form is not filled out. There are also numbers corresponding to each of the letters. There is also “I-J” used twice.

Die Nachricht wurde also wohl am Tag nach dem D-Day (D-Day +1) versendet. Das von Patrick erwähnte “Message Book M-210” wird beispielsweise auf der Cryptomuseum-Webseite von Paul Reuvers und Marc Simons beschrieben:

This small message book was used for writing down encrypted or decrypted messages. It is small enough to be stowed inside one of the pockets of the canvas carrying bag. Carbon paper is used to create a duplicate when writing down a message. The duplicate page is thinner than the primary one, so that it can be fitted inside a pigeon capsule more easily. Note that the duplicate pages of the M-210A book are thinner that those of an M-210 book.

Es könnte also sein, dass auch die “D-Day+1”-Nachricht mit einer Brieftaube transportiert wurde. Allerdings war das “Message Book M-210” bei den US-Amerikanern in Gebrauch, während das seit Lngerem bekannte Brieftauben-Kryptogramm von den Briten verschickt wurde.

Lösungsansätze

Die “D-Day +1”-Nachricht lässt sich als Folge von Buchstabe-Zahl-Paaren lesen:

Q4 Z7 E2 C8 O3 D3 …

Dies spricht für ein Verfahren, bei dem eine Tabelle zum Einsatz kam, deren Spalten mit Zahlen und deren Zeilen mit Buchstaben (order umgekehrt) markiert waren. Auffällig ist, dass I und J anscheinend eine Einheit bildeten. Es gab also 25 Buchstaben und 10 Zahlen (0-9) zur Auswahl. Mir ist leider kein Verschlüsselungsverfahren bekannt, das hierzu passt. Aber vielleicht wissen meine Leser mehr.

Vielen Dank an Patrick Hayes für dieses spannende Krypto-Rätsel! Wer etwas dazu sagen kann, möge sich melden.

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Further reading: An encrypted letter from World War 2

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13501820

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/763282653806483/

Kommentare (18)