Endlich gibt es wieder eine HistoCrypt. Schon die ersten beiden Tage waren einen Besuch wert.

English version (translated with DeepL)

Zum ersten Mal seit Beginn der Corona-Epidemie findet momentan wieder eine HistoCrypt-Konferenz als Präsenz-Veranstaltung statt. Ort des Geschehens ist Amsterdam, wo der “Local Chair” Karl de Leeuw das Trippenhuis als Veranstaltungsort gemietet hat.

Viele bekannte Gesichter

Die HistoCrypt ist die wichtigste europäische Veranstaltung zur Krypto-Geschichte. Nachdem die letzte Ausgabe 2019 in Mons (Belgien) abgehalten wurde, fiel die für 2020 in Budapest geplante HistoCrypt wegen Corona aus, woraufhin 2021 eine Online-Version stattfand. Vom 19. bis 21. Juni gibt es nun die Ausgabe 2022 in Amsterdam. 48 Teilnehmer sind dabei.

Wie immer, stehen zahlreiche Vorträge zur Krypto-Geschichte auf dem Programm. Viele der Teilnehmer dürften Cipherbrain-Lesern bekannt sein, darunter Paolo Bonavoglia, Marek Grajek, Karl de Leeuw, Magnus Ekhall …

… , David Scheers, Gerhard Strasser, Benedek Láng, George Lasry (letzterer gab seine beiden Vorträge per Videokonferenz, da er nicht persönlich kommen konnte) und Dermot Turing. Besonders gefreut habe ich mich, dass der Australier Richard Bean dabei ist, den ich noch nie persönlich getroffen haben:

Richard hielt einen Vortrag über die “Kryptos”-Skulptur. Bei Joachim von zur Gathen ging es um den Zodiac-Killer und die Z340-Nachricht. George Lasry sprach zunächst über die Sicherheit des Schlüsselgeräts 41 (Hitlermühle), deren Funktionsweise erst sein Kurzem im Detail bekannt ist. Später trug er über die Dechiffrierung dreier verschlüsselter Dokumente vor. Paul Reuvers und Marc Simons erhielten für ihre Keynote-Präsentation über die Operation Rubikon viel Beifall. Magnus Ekhall berichtete über die Desch-Bombe, eine US-Enigma-Knack-Maschine, über die auch Dermot Turing vortrug. Nils Kopal und Michelle Waldispühl zeigten, wie sie zwei verschlüsselte Briefe aus dem 16. Jahrhundert gelöst hatten. Nino Fürthauer referierte zum Doppelwürfel, der auf diesem Blog auch schon öfters eine Rolle gespielt hat.

Nils Kopal führte in der Poster-Session die Software CrypTool vor, die immer mehr Funktionen aufweist. Auch Paolo Bonavoglia zeigte ein Poster.

Morgen gibt es weitere Vorträge. Der Konferenzband ist online zugänglich. Ich selbst muss als “Steering Comittee Chair” dieses Mal zwar auf einen Vortrag verzichten, dafür “durfte” ich das Business Meeting leiten. Mein Amt habe ich bei dieser Gelegenheit an Dermot Turing weitergegeben, bei dem es zweifellos in guten Händen ist.

Tobias Schrödels Vortrag

Zu den Höhepunkten zählte ohne Zweifel der Vortrag von Tobias Schrödel, der Lesern dieses Blogs ebenfalls bekannt sein dürfte. Leider konnte Tobias (wie einige andere) nicht nach Amsterdam kommen und hielt seinen Vortrag daher per Videokonferenz. Als hervorragender Redner zog er das Publikum auch per Video schnell in seinen Bann.

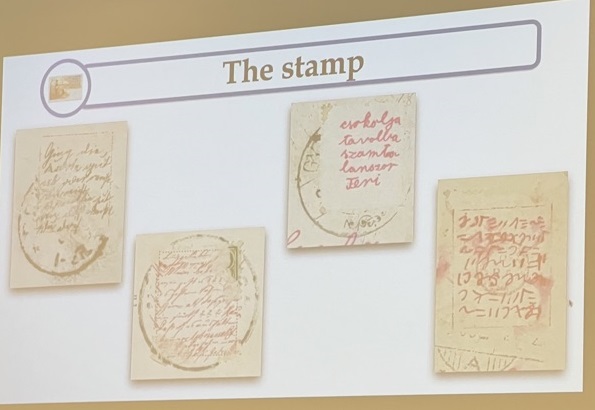

Tobias’ Thema waren verschlüsselte Postkarten. Die folgende Folie zeigt beispielsweise Nachrichten, die unter der Briefmarke versteckt wurden:

Normalerweise stehen die verschlüsselten Nachrichten natürlich nicht unter den Briefmarken, sondern an der üblichen Stelle. Interessant fand ich vor allem ein paar Statistiken, die Tobias vorstellte. Eine davon bezog sich auf der Zeit, in der die verschlüsselten Karten in seiner Sammlung entstanden sind:

- 1880-1889: 6

- 1890-1899: 21

- 1900-1909: 148

- 1910-1919: 161

- 1920-1929: 4

- 1930-1939: 1

- 1940-1949: 3

- 1950-1959: 0

- 1960-1969: 2

Dies bedeutet, dass etwa 90 Prozent der verschlüsselten Postkarten in den ersten beiden Jahrzehnten des 20. Jahrhunderts entstanden sind. Dies gilt wohl auch für diejenigen Karten, die ich auf Cipherbrain vorgestellt habe.

Ebenfalls bestätigen kann ich die Aussage von Tobias, dass nahezu alle verschlüsselten Postkarten mit einer einfachen Buchstaben-Ersetzung (einschließlich der Caesar-Chiffre, des Pigpen-Verfahrens und des Morse-Alphabets) verschlüsselt wurden. In seiner Sammlung gibt es außerdem ein paar Kurzschrift-Postkarten, die aber nicht im engeren Sinne verschlüsselt sind. Verschlüsselte Postkarten, auf denen eine komplexere Chiffrier-Methode eingesetzt wurde, sind extrem selten.

Ein Beispiel

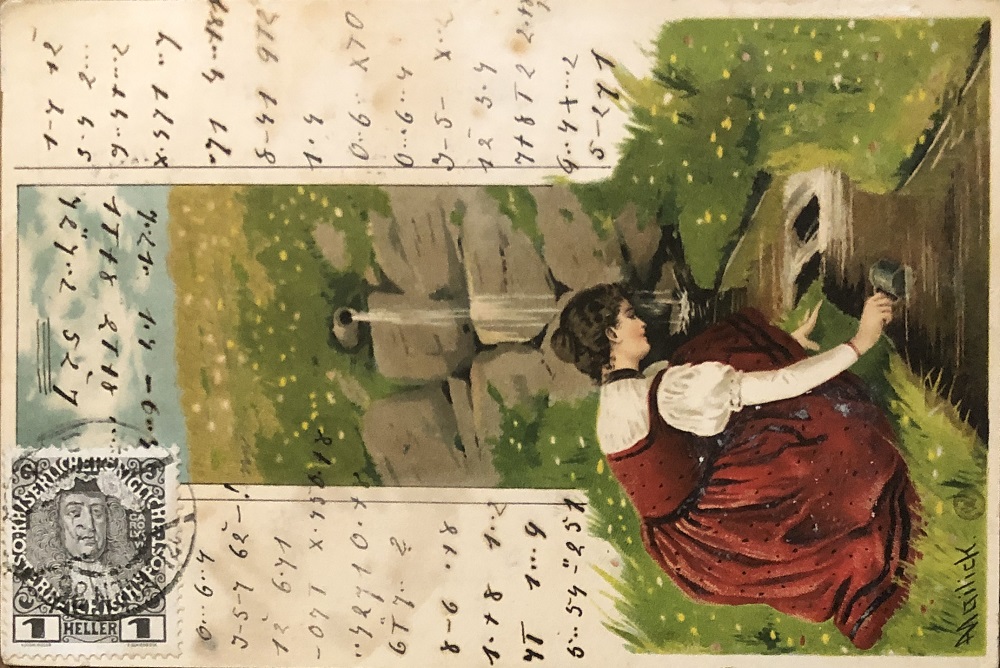

Die folgende Postkarte aus Gföhl in Österreich hat Tobias in seinem Vortrag zwar nicht gezeigt, sie stammt jedoch aus seiner Sammlung:

Kann ein Leser dieses Kryptogramm lösen?

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Further reading: HistoCrypt 2019: A video and a few more photos

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13501820

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/763282653806483/

Kommentare (14)