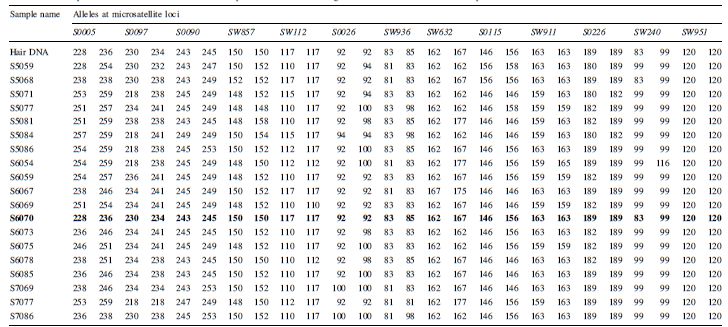

STR-Profile aus der Haarprobe (erste Zeile) und den den 19 toten Schweinen. Die Spalten entsprechen den Merkmalen in den 13 STR-Systemen. Das zum Haar passende Schweineprofil ist fett markiert; aus [1]

Nur durch den Einsatz einer robusten und reproduzierbaren WFS-Methode konnte es in diesem Fall also gelingen, den Schützen zu ermitteln, dessen Projektil nicht nur Schwein 6070 sondern auch einen wertvollen Jagdhund getötet hatte. Die Ergebnisse wurden der ermittelnden Fortbehörde mitgeteilt und werden die Grundlage zur juristischen oder sonstwie bewältigten Beilegung dieser mißlichen Angelegenheit sein. Und natürlich hätte man analog vorgehen können, wenn statt eines Hunds versehentlich ein Mensch getroffen worden wäre…

____

Referenzen:

[1] Schleimer, A., Frantz, A. C., Lang, J., Reinert, P., & Heddergott, M. (2016). Identifying a hunter responsible for killing a hunting dog by individual-specific genetic profiling of wild boar DNA transferred to the canine during the accidental shooting. Forensic science, medicine, and pathology, 12(4), 491-496.

[2] Linacre A, Gusma˜o L, Hecht W, Hellmann AP, Mayr WR, Parson W, et al. ISFG: recommendations regarding the use of nonhuman (animal) DNA in forensic genetic investigations. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2011;5:501–5.

[3] Alexander LJ, Rohrer GA, Beattie CW. Cloning and characterization of 414 polymorphic porcine Microsatellites. Anim Genet. 1996;27:137–48.

[4] Hampton JO, Spencer PBS, Alpers DL, Twigg LE, Woolnough AP, Doust J, et al. Molecular Techniques, wildlife management and the importance of genetic population structure and dispersal: a case study with feral pigs. J Appl Ecol. 2004;41:735–43.

[5] Frantz AC, Cellina S, Krier A, Schley L, Burke T. Using spatial Bayesian methods to determine the genetic structure of a Forensic Sci Med Pathol 123 continuously distributed population: clusters or isolation by distance? J Appl Ecol. 2009;46:493–505.

Kommentare (63)