This page lists open research questions in historic cryptology. It is inspired by similar lists published by David Kahn and Craig Bauer. It is planned to continuously extend this list. Comments and suggestions are welcome.

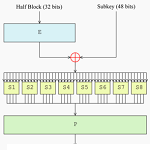

DES Candidates

In the 1970’s the the US standards body NBS (now named NIST) solicited proposals for an encryption algorithm. Many submissions came in, but none turned out to be suitable. A second request was issued, this time there was one serious candidate – it was to become the DES. Nothing is known about the non-accepted submissions. Looking at them from today’s point of view would be very interesting.

Leighton Files

In the 1980’s, history professor Albert Leighton (1919-2013) encountered other historians who were not able to read encrypted documents in the archives. He started to collect these encrypted documents and solved many of them himself or had them solved by other cryptologists. Meanwhile Leighton has died. It is not known in the crypto history community what has happened to his cryptogram collection. Leighton was a professor at SUNY Oswego (1964-1985). After his retirement he moved to San Antonio, Texas.

Japanese crypto from a Japanese point of view

Japanese encryption in WW2 and the years before is a very interesting topics. Much has been published about it based on US sources. However, almost no research has been done in Japanese archives.

Cryptology in the Falkland War

Rumors say that cryptology played an important role in the Falkland War (a war between Great Britain and Argentina in 1982). Many details are still classified. Nevertheless, there a number of sources are available that can be used for research. A blog article of mine (in German) gives an overview.

Cipher machines from the “Golden Triangle”

Almost all commercial encryption machines in the Cold War were provided by three companies located in the area of Zurich, Switzerland: Crypto AG (Hagelin), Gretag, and Brown Boveri. While Hagelin’s history is relativley well researched the other two crypto suppliers from the “Golden Triangle” have received almost no attention from crypto historians.

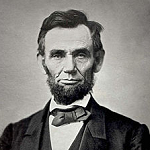

Assassination of Lincoln

John Wilkes Booth, the murderer of Abraham Lincoln, communicated in cipher with his fellow conspirators. Some of the encrypted messages were used on court. The details have never been researched.

Literature: https://www.fbi.gov/about-us/lab/forensic-science-communications/fsc/april2006/research/2006_04_research01.htm

Automated Cryptanalysis

Several articles in the scientific magazine Cryptologia cover automated cryptanalysis. Most of these articles were published in the 1980’s. An overview and an update would be helpful.

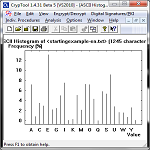

Cryptanalysis Software

Several software tools for solving cryptograms are available (for instance CrypTool or Bion’s Gadget). However, a comprehensive, user-friendly cryptanalysis software does not exist.

Vowel detection

There are several simple algorithms for vowel detection (e.g. Sukhotin). It would be interesting to apply them to cryptograms like the Dorabella cipher, Voynich Manuscript, Rohonc Codex, Zodiac cryptograms, Blitz cipher, Scorpion cryptogram, Codex Seraphinianus, Ashmole cryptogram and others.

Chinese Cryptology

The Chinese writing system is not well suited for encryption. Anyway, some encryption methods are known. An overview would be helpful.

Breaking codes and nomenclators

Codes (based on codebooks) and nomenclators used to be the most popular way of encryption. Almost no literature on how to break them is available.

Initial letters cryptograms

A number of historical cryptograms consist of word initials, for instance the Somerton Man cryptogram, and the Action Line cryptogram. An overview and solution techniques would be helpful. Initial letter cryptograms were espcially popular among the Freemasons and similar societies.

Literature: https://scienceblogs.de/klausis-krypto-kolumne/mnemoic-ciphers/

Italian Cipher Machines

Several Italian cipher machines (from OMI and Olivetti) from WW2 and the Cold War area are known. Some of them are available in collections. Almost nothing is known about the history of these machines.

The Rehmann Diskret encryption machine

The Rehmann Diskret is an intersting encryption machine built around 1900. Its history is as good as unknown.

The Beyer encryption machine

The Beyer Cryptograf is an intersting encryption machine built around 1930. Its history is as good as unknown.

The Cryptocode Encryption Machine

The Cryptocode is an intersting encryption machine built around 1928. Its history is as good as unknown.

https://www.jproc.ca/crypto/cryptocode.html

Rubic’s Cube Encryption

A Rubic’s cube can be used for encryption. Some basic papers are available, but more research would be helpful.

M-138 Cryptanalysis

The M-138 is a simple encryption device, but it is presumably hard to cryptanalize.

Cryptanalysis of the Fleissner Grill

The Fleissner Grill is a well-known tool that is used for a transposition cipher. The security of the encryption depends on the size of the grill. A paper about the cryptanalysis of Fleissner Grill messages would be interesting.

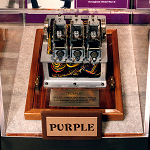

3D Models of Lost Encryption Machines

Many interesting encryption machines are lost (i.e. no copy is known to exist any more). Examples are the Kryha Elektric, Purple, T-43, SG 39, Bomba, and Nightingale. In some cases photographs are available, in others only the function is known. In addition, there are numerous patents of encryption machines which have never been built. With today’s design software (e.g. Blender, AutoCAD, SolidWorks) it should be possible to create models of these machines and to produce 3D models as well as photo-realistic pictures.

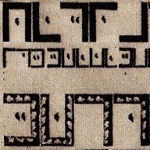

Pigpen Cipher Overview

The pigpen cipher has been a popular cipher method for centuries. A comprehensive overview on its history has never been made.

Encryption of Analog Facsimiles (Wirephotos)

Before the modern fax technology came up, analog facsimiles (wirephotos) were in use for more than a century. Several engineers, including the well-known William Friedman, invented encryption devices for this technology.

Secure Manual Encryption (Solitaire, Handycipher, DCT, Book Ciphers, Rubik)

Developping an encryption algorithm that can be used without the support of machines or devices is a challenge.

Cryptograms Published by Intelligence Organisations for Recruitment

The NSA, the US Navy, GCHQ and many other intelligence organisations have published cryptologic puzzles in order to attract skilled codebreakers for recruitment. These cryptologic puzzles have never been gathered, no systematic overview has been published.

Cryptanalysis of Homophonic Ciphers

Homophonic ciphers were in widespread use (among others by the Zodiac Killer). A comprehensive work on how to break them would be helpful.

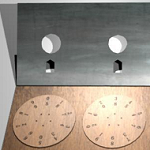

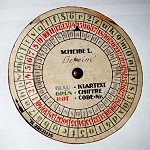

Cipher Discs and Cipher Slides

Cipher discs and cipher slides have been known for over 500 years. The are different variants and different ways of usage. Neither a comprehensive history nor a comprehensive theoretical treatment of cipher discs/slides is available.

Encrypted Telemetry

Wireless telemetry was invented around 1930. Telemetry (for instance for missiles) is security critical and therefore needs encryption. Encryption in early telemetry has never been researched.

Encrypted Gravestones

Several gravestones with encrypted inscriptures are known in the crypto history community. Two are located in New York City, others in Montreal, the UK and Russia. Are there more? This question has never been answered.

History of the Fialka

The Fialka is a Russian rotor encryption machine from the Cold War era. Numerous Fialka copies are available in museums and private collections. However, not much is known about the history of this machine. Filling this gap certainly requires research in Russian archives. In addition, it should be possible to find contemporary whitnesses in the former communist countries.

Cipher Wheels

Cipher wheels played an important role in the history of cryptology. Many models are known: Fontana’s Columpna, Gripenstierna’s wheel, Jefferson’s wheel, Baizeries’ wheel, the M-94, the Cryptocode, the Swiss Army wheel, the Heimsoeth & Rinke wheel, Corry Doctorow’s wedding ring and more. An overview about the history, the mathematics and the cryptanalysis of cipher wheels would be interesting.

The Tibbe-Mulders Crypto-Psychic Experiment

In 1948 parapsychologist Robert Thouless started an experiment: He published an encrypted message and announced that he would reveal the key after his death. With this experiment (it prooved to be unseccessful) Thouless wanted to test if communication with a dead person is possible. In 1980 Tribbe and Mulders asked their readers to create cryptograms with the same purpose and to send them to the “Survival Research Foundation” for archival. It is not known how many encrypted messages were received and what happened to them. The Survival Research Foundation obviously does not exist any more. It would be interesting to learn more about this strange experiment.

Cryptology and Art

Sculptures like Kryptos and the Cyrillic Projector have encrypted inscriptions. Encrypted books like the Codex Seraphinianus and the Book of Woo represent pieces of art. Porta’s cipher disk and some other cipher devices are pieces of art, as well. There are many other contact points between art and cryptology. A paper about this subject would certainly be interesting.

Classic Cryptology in Crime Investigation

Cryptanalyzing manual encryption methods still plays a role in modern police work. The FBI even operates a unit (the CRRU) which breaks the codes of criminals. In other countries similar institutions are known to exist. The success ratio of police codebreakers is said to be very high (about 99 percent), which means that only in very few cases the help of external experts or of the public is needed (the McCormick case is one of these few exceptions). For obvious reasons, police codebreakers don’t talk much about their work. Therefore, not much is known about this topic in public. Anyway, some information is available and it should be possible, even for an outsider, to write a paper about classic cryptology in crime investigation.

Encryption Methods for Personal Use

Many encryption algorithms have been developed for personal use only. For instance, an author of an encrypted diariy usually doesn’t assume that there is a legitimate recipient except for the writer himself. It goes without saying that personal use encrypion methods differ from others (especially if they are designed by a layman). In many cases personal use methods include steps and tricks which are confusing for a cryptanalyst. Changes in the algorithm and non-deterministic parts are quite common. Many personal use methods are not based on keys (if an algorithm is used only by one person a key is less important). A comprehensive treatise encryption methods for personal use is not available in the crypto community today. Such a treatise might be helpful, as many unsolved cryptograms (for instance the Voynich Manuscript, McCormick’s notes, the Taman Shud cryptogram, Hampton’s notebook, and the Codex Rohonci) might have been encrypted for the respective author only.

The Rise and Fall of Snake Oil

Cryptology has always attracted dabblers. This became once more evident when around 1995 the internet had its break-through. While skilled security experts developed sophisticated crypto solutions for the internet, there was also a considerable number of bogus encryption systems. Amateur cryptologists published their “unbreakable” algorithms in in online forums, even professional software suppliers created their own weak methods instead of using DES or RSA. Very often, these products were marketed with shady promises (“military-grade encryption”, “best possible privacy”). Conspiration theories became a part of selling strategies (“the NSA can break everything except this”). Crypto expert Bruce Schneier coined the expression “snake oil” for this kind of encryption technology. However, the heyday of snake oil lasted only a few years. As more and more people learned the basics of cryptology it became common knowledge that using standard encryption methods is the best way to achieve security. Meanwhile snake oil has almost vanished. However, it is a part of crypto history that should be remembered. A historical research paper about snake oil would certainle be worthwhile.

Cryptology and Magic

In the Middle Ages and the early Modern Age cryptology was not clearly separated from magic. Encryption was often considered a magic act, there were even encryption methods including supernatural forces. Some secret writing systems were not developed for message confidentiality but for magic purposes. On the other hand, cryptanalysis was sometimes presented as a supernatural art, too. Not before the Age of Enlightenment cryptology lost its magic connotation. The history of cryptology and magic has never been researched in detail.

The Whittingham-Collingwood Cryptograph

The Whittingham-Collingwood cryptograph is a cipher machine design probably originating in the 1920’s. The only known copy is owned by a navy museum in Portsmouth, England. Almost nothing is known about the history of this device. The encryption principle of the Whittingham-Collingwood cryptograph is unique, it has never been examined by a cryptologist.

Cryptology in Advertisement

Using encryption for marketing purposes has a long tradition. Among other products, Kix, Odol and Ovaltine have been advertised with secret messages. Cryptographic toys (e.g. cipher wheels) are popular promotional gifts. Movies, CDs, books, radio mshows and events were brought to public attention with crypto games. The history of cryptology is advertisement has never been told.

Cryptology in in the Movies

In many movies cryptology plays a role. Well-known examples are “Enigma”, “U-571”, “Wind Talkers”, and “Mercury Rising”. A more comprehensive list would be an interesting research project.

Candidates:

- Encrypted books

- Russian cryptanalysis

- Encrypted inscriptions

- mistakes

- tops and flops

- Encrypted diaries

- Cryptographic toys

- Codebreaking machines

- Women in encryption

Kommentare (4)