The encryption codes of German spies in World War 2 are still little researched. Today I will introduce an interesting spy telegram that was sent from Buenos Aires to Hamburg in 1940.

Intelligence work plays an important role in every war. In World War 2, the Germans operated their secret service “Abwehr” in order to gather information of military relevance about their enemies.

German spy codes

The Abwehr tried hard to deploy a worldwide network of spies, but they were never as successful as other secret services, like the CIA, the Mossad or the KGB. As the war went on, Abwehr director Wilhelm Canaris together with some of his closest colleagues became important opponents of Hitler. Canaris was arrested and murdered in a Nazi concentration camp in April 1945.

One of the Abwehr’s strategies was to send secret agents to enemy countries and to other places of interest. These agents were camouflaged as businessmen, travellers, journalists or somehow else. Some of the information they were looking for was easily available by observing harbours or simply reading newspapers. In addition, Abwehr agents tried to hire local people with access to less obvious information. While this did work in many cases, the Abwehr was not especially successful in recruiting high-ranked persons in the military or the government.

One major challenge for the Abwehr was to communicate with their foreign agents. Some messages were sent by radio or telegram, others by mail. Both steganography and cryptography played an important role. The USA, Great Britain and some other countries established censorship agencies with thousands of employees in order to search for spy messages in the mail and in telegrams.

So far, the encryption and steganography techniques used by the Abwehr are little researched. There must have been many different methods in use. Of course, ciphers used by spies had to be simple, cheap and unobtrusive. Encryption machines like the Enigma could not be used. Usually, the only tools available for enciphering and deciphering were paper and pencil.

A spy message from Argentina

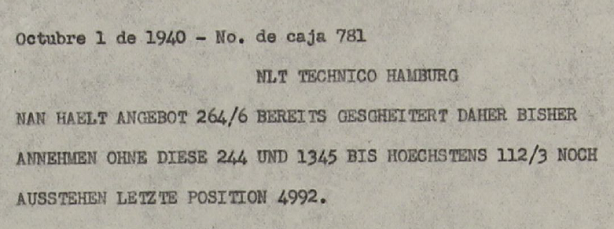

The following telegram (today kept by the British National Archives) was sent by a German named Ottomar Müller from Buenos Aires, Argentina, to a company named NLT Technico in Hamburg, Germany:

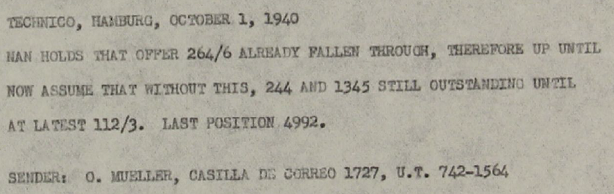

Here’s the English translation of it:

The telegram has the appearance of a commercial note. It contains several code numbers, which was quite common for a business telegram of the time. The meanings of code numbers were listed in codebooks. The main purpose of using code numbers was to make telegrams shorter (and therefore cheaper), while privacy only played a minor role.

The telegram above was forwarded to British crypto experts, who recognised that it was a spy message. The two code numbers containing a slash were derived from a German-English dictionary (e.g., 264/6 means page 264, word number 6).

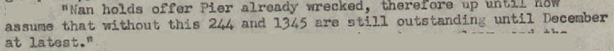

With the dictionary the crypto experts found out that 264/6 stands for “pier” and 112/3 for “December”. With this information, the telegram can be partially encrypted:

The British codebreakers could not find out what the numbers 244, 1345 and 4992 mean. They might stand for persons, places or time/date information. My guess is that the secret message only consists of the five code numbers, while the rest is meaningless. If I’m right, the message reads “Pier 244 1345 December 4992” – whatever this means.

Has anybody ever heard of a company named NLT Technico? What do the numbers 244, 1345 and 4992 mean? And who is “NAN”? If you have an idea, please tell me.

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Further reading: Who can make sense of a child murderer’s encrypted notes?

Kommentare (9)