Blog reader Nils Kopal has purchased a copy of a famous 16th century crypto book. Inside he found more than he had expected. Can a reader tell him what these additional texts and illustrations mean?

The book De furtivis literarum notis by Giambattista della Porta is generally considered the best cryptology book of the Renaissance era (check here for an online version at Google Books). Porta, a genius and polymath, was an extremely productive author with an interest in agriculture, physics, engineering, philosophy, pharmacology, and cryptology. In addition, he published over 20 theatrical pieces.

An outstanding book

Though cryptology was only one of many of his interests, Porta was an excellent cryptologist. US encryption expert Charles J. Mendelsohn once said: “He [Porta] was, in my opinion, the outstanding cryptographer of the Renaissance. Some unknown who worked in a hidden room behind closed doors may possibly have surpassed him in general grasp of the subject, but among those whose work can be studied he towers like a giant.”

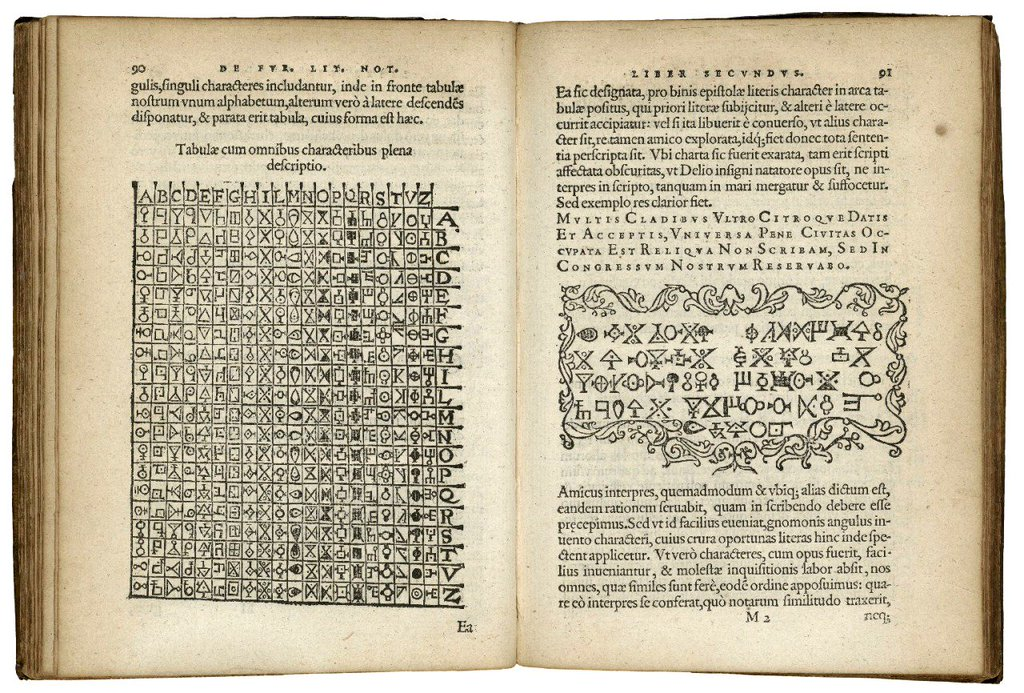

Among other things, De furtivis literarum notis (published in 1563) contains the first known mention of the letter pair substitution (on the left side of the following scan):

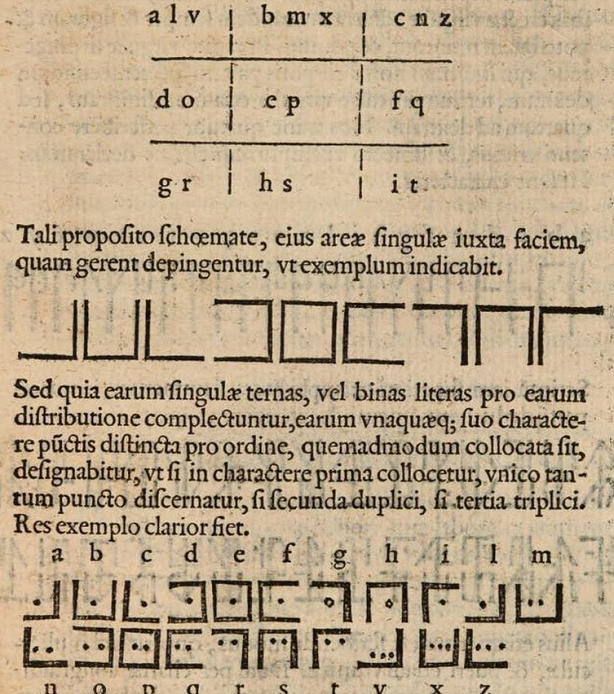

In addition, De furtivis literarum notis describes a variant of the Pigpen cipher:

Some of Porta’s ideas only came into use centuries later.

Nils Kopal’s copy

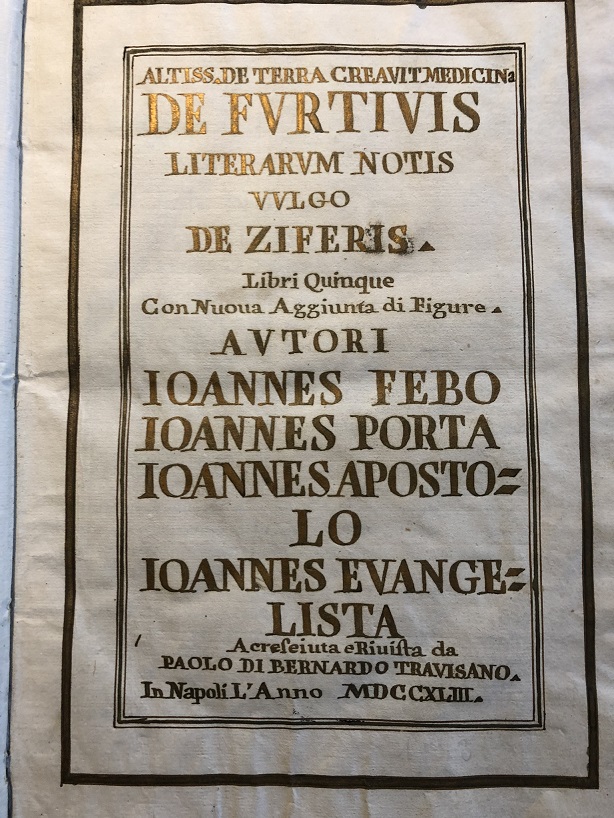

Nils Kopal, crypto history expert, CrypTool developer and reader of this blog, has recently purchased a copy of De furtivis literarum notis. It’s not an original from 1563 but a beautiful reprint from 1743.

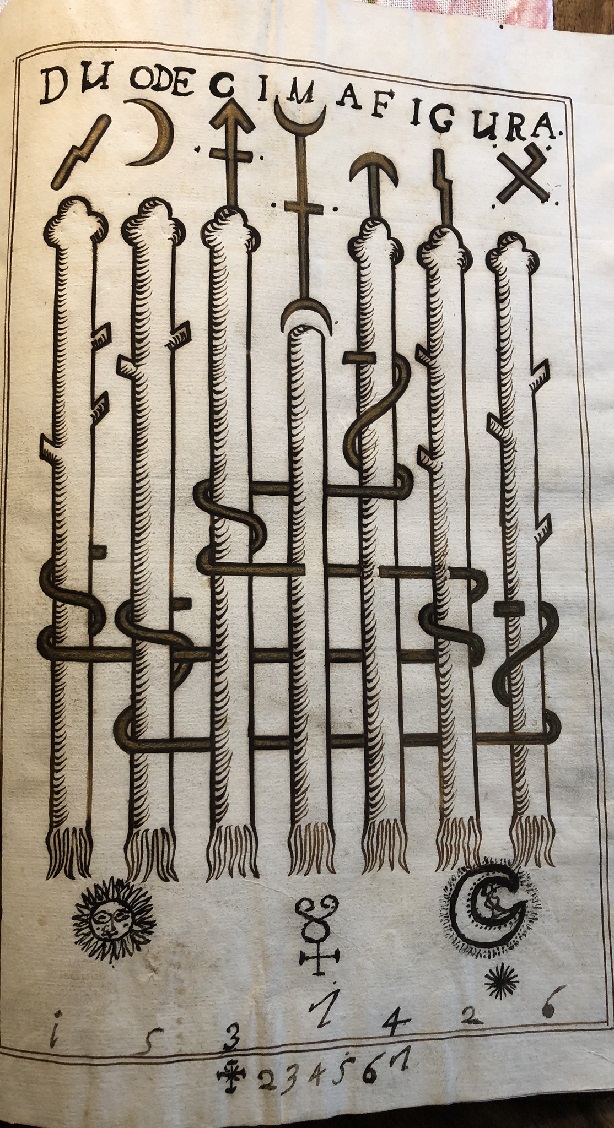

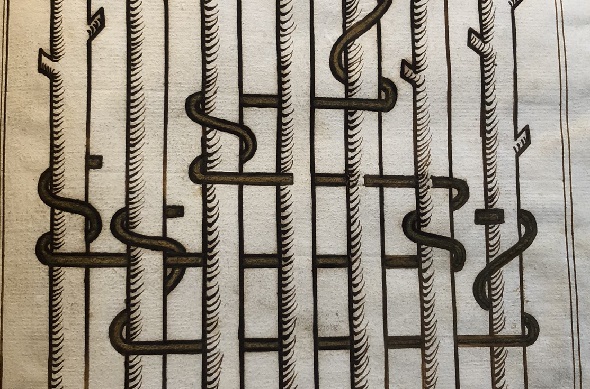

What is especially interesting about this edition is that it contains some additional material. After the actual content of the book, 19 illustrations follow. Here are the first three of these:

As far as I can see, these pictures have nothing to do with cryptology. Anyway, Nils and I wonder what they mean. Can a reader say more about these illustrations?

The astrological part

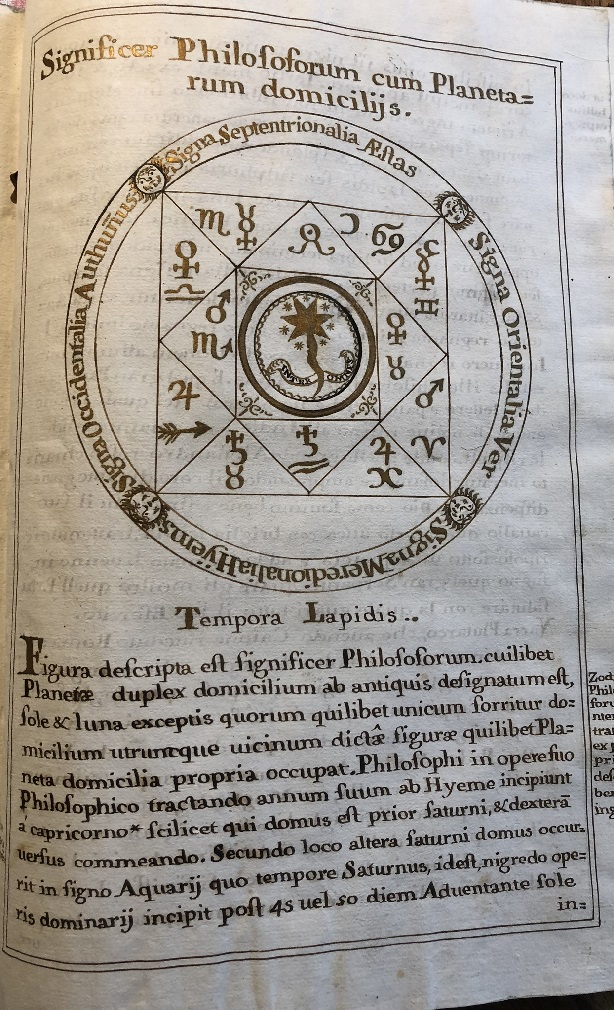

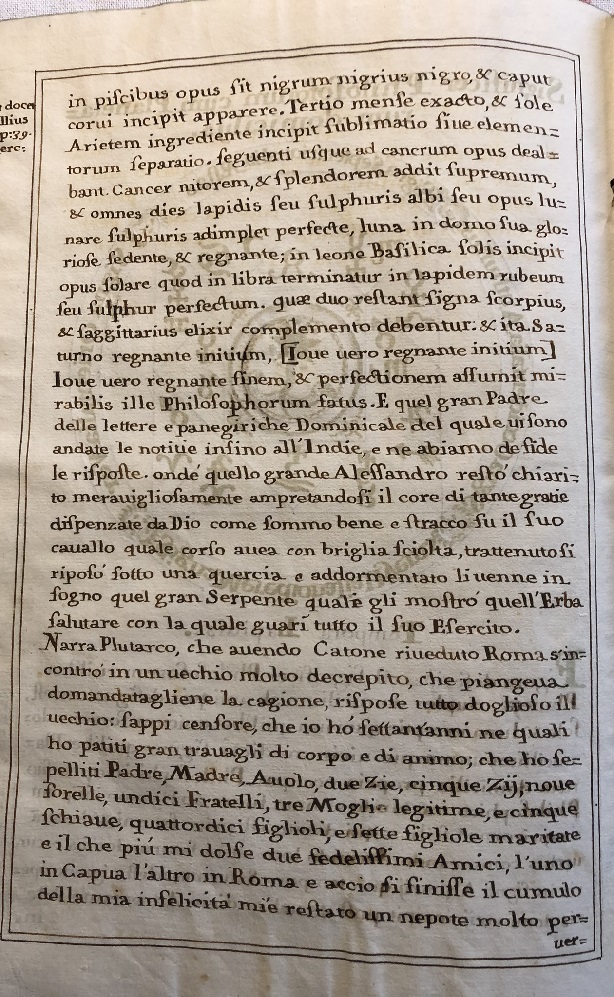

The last part of the 1743 version of De furtivis literarum notis is formed by an astrological treatise consisting of four pages containing two illustrations:

Does a reader know what exactly this treatise is about and what this final illustration means? If so, please let Nils and me know.

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Further reading: Who can break the cryptograms of Civil War spy Robert Bunch?

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13501820

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/763282653806483/

Kommentare (13)