A telegram sent by a British colonel in 1916 still waits to be solved. The encryption method used might be a letter-pair substitution.

Blog reader Tony Gaffney, who recently broke the encrypted diary of a pedophile priest, has made me aware of an interesting cryptogram that was published in 2014 by the Bury Times, a local newspaper from Bury, England.

An encrypted telegram

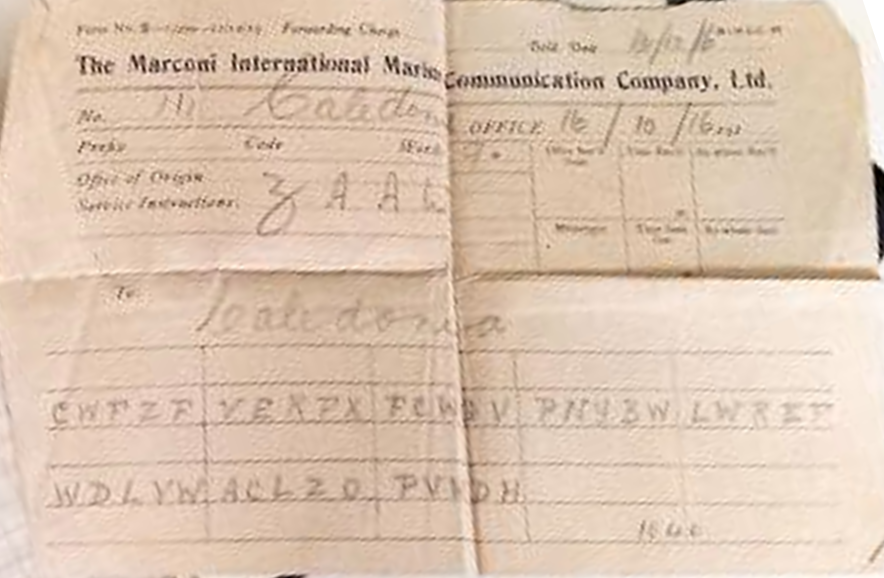

The Bury Times article reports on an encrypted message sent in 1916 by a Colonel Frederick Arthur Woodcock. When the article was published, this message was unbroken and it probably still is. Here is a scan of it (sorry for the bad quality):

Source: Bury Times

As can be seen, this is a telegram. It was sent on October 16th, 1916, to a recipient named Caledonia. The Caledonia probably was a ship (Wikipedia lists several ships of this name). The telegram is noted on a form of the Marconi International Marine Communication Co. (M.I.M.C.Co.), a subsidiary of the Marconi Company. Here’s a M.I.M.C.Co. avertisement poster published in 1917 (it has no relationship to the Woodcock telegram):

Source: Grace’s Guide to British Industrial History

Considering that Woodcock was a colonel, that the recipient was a ship crew and that the telegram was sent during the First World War, it seems plausible that the message was military in nature. The telegram form doesn’t look military to me, but perhaps a commercial radio station was used to transmit military message.

Here’s my transription of the message:

CWFZF VEXPX FCWGY PNYBW LWREF WDLYW ACLZO PVWDH

The key (?)

The most popular method to encrypt telegrams in WW1 was using a codebook.

In the military, many codes were super-encrypted, which means that an additional encryption step was applied on the codewords used (e.g., adding the current date). The message on the Woodcock telegram is consistent with a codebook encryption. Codebooks with five-letter codewords were quite common.

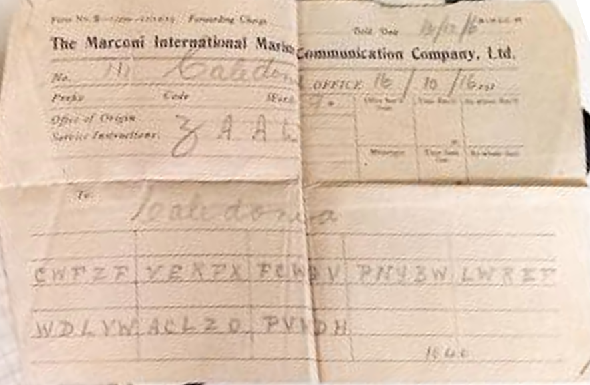

However, according to the Bury times article, the Woodcock telegram was not encrypted with a code but with a cipher based the following key, which is contained in a notebook Colonel Woodcock owned:

Source: Bury Times

However, in my view, this is not a key but the result of an encryption, i.e. a ciphertext. It looks similar as the telegram message. I don’t think that these lines were produced by looking up words in a codebook or by a codebook super-encryption.

As the text contains vertical lines that separate letter pairs, the cipher used might be a letter-pair substitution, e.g., a variant of the Playfair cipher. The Playfair was a quite common cipher in the first half of the 20th century. If Woodcock really used a cipher of this kind, the ciphertext might be too short to break the message.

Tony Gaffney has emailed the librarian in Bury asking if this cryptogram was ever solved and if it is possible to get more scans – but he didn’t receive a reply. Can a reader solve this mystery anyway?

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Further reading: The Top 50 unsolved encrypted messages: 46. Unsolved ADFGVX cryptograms from World War 1

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13501820

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/763282653806483/

Kommentare (18)