French crypto history expert Jean-François Bouchaudy has found something very rare: three original messages encrypted with an M-209 cipher machine. One of these is still unsolved.

Everybody interested in crypto history should read Cryptologia, a scientific magazine mainly dedicated to the history of encryption. Over the last four decades, numerous interesting articles have been published there (including a few written by me), and in recent years the number and quality of the publications has even increased. At the moment, the Cryptologia website lists 13 papers in the “latest articles” section. Among these are two articles about the Voynich manuscript and one about the Enigma. I’m sure, Cryptologia will see further growth in the future.

To my regret, Cryptologia articles are quite expensive – but many of them are worth the price.

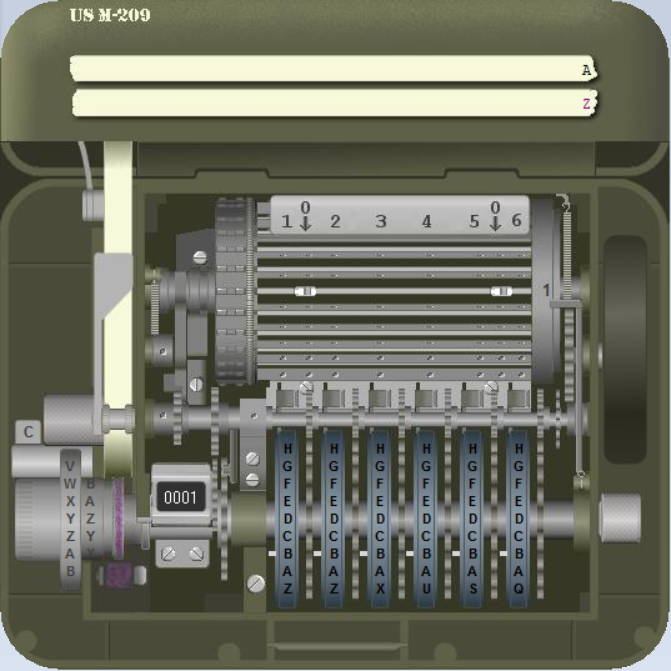

The M-209 cipher machine

Another recent Cryptologia article (written by Jean-François Bouchaudy) is about messages encrypted with the encryption machine M-209.

Cryptomuseum (used with permission)

With about 140,000 copies built, the M-209 is probably the most produced encryption machine in history. The US military used this device in World War II, and it remained in active use through the Korean War. According to Bouchaudy’s article, the M-209 was also used in France during WW2, when US troups introduced this machine to their French allies.

The M-209 was used as a field cipher. It was designed to be small, robust, and lightweight. Instead of a keyboard (like the Enigma) it contained a letter wheel (the grey wheel on the left side). For each letter to be encrypted, the operator had to adjust this letter with the letter wheel and press a lever, which made the machine print the corresponding ciphertext letter on a paper strip. A great M-209 simulator has been programmed by Dirk Rijmenants.

Rijmenants

The M-209 uses three different keys (the recipient needs all of them to decrypt a message):

- Wheels: The position of the six wheels at the front is a key (this key was usually different for every message encrypted). Wheels #1, #2, #3, #4, #5, and #6 are labeled with 26, 25, 23, 21, 19, and 17 letters, respectively.

- Pins: Every wheel has a pin for every letter, which can be active or inactive. Activating or deactivating a pin is only possible when the cover is open.

- Lugs: Inside the machine there’s a rotating cage with 27 bars. Each bar in the cage has two movable lugs. Each lug may be set against any of the six wheels or set to a neutral position.

Originally, I thought that the M-209 was less secure than the Enigma. According to George Lasry, a leading specialist in breaking machine ciphers, this can be disputed. George wrote:

- The best modern ciphertext-only algorithm for Enigma (Ostward and Weierud, 2017) requires no more than 30 letters. My new algorithm for M-209 requires at least 450 letters (Reeds, Morris, and Ritchie needed 1500). So the M-209 is much better protected against ciphertext-only attacks.

- The Turing Bombe – the best known-plaintext attack against the Enigma needed no more than 15-20 known plaintext letters. The best known-plaintext attacks against the M-209 require at least 50 known plaintext letters.

- The Unicity Distance for Enigma is about 28, it is 50 for the M-209.

- The only aspect in which Enigma is more secure than M-209 is about messages in depth (same key). To break Enigma, you needed a few tens of messages in depth. For M-209, two messages in depth are enough. But with good key management discipline, this weakness can be addressed.

George’s conclusion: If no two messages are sent in depth (full, or partial depth), then the M-209 is much more secure than Enigma.

The M-209 had not to be unbreakable, as it was only used as a field cipher. Typically, M-209 encrypted messages contained information like position reports, material orders, weather reports or warnings, which usually lost their value within days or even hours.

During World War II several German crypto units independently from each other found ways to break the M-209. In 2004 I had the chance to talk to a German WW2 codebreaker named Reinold Weber, who reported about a codebreaking machine German specialists constructed in order to decipher M-209 messages.

Even decades later, when the M-209 was long out of use, crypto experts developed new attacks on this machine. E.g., in the late 1970s, Jim Reeds, Robert Morris, and Unix inventor Dennis Ritchie introduced a ciphertext-only method for recovering keys from M-209 messages. In 1977 US cryptologist Wayne G. Barker published a book titled Cryptanalysis of the Hagelin Cryptograph. It describes a method for breaking the M-209 and includes a number of M-209 ciphertexts for the reader to solve.

And then, George Lasry developed new M-209 breaking techniques.

Three original messages

In his afore-mentioned Cryptologia article, Jean-François Bauchaudy writes that he has found three original cryptograms encrypted with an M-209. They date from 1944 and come from the 1st French Army. Since the security rules in the military required messages of this kind to be destroyed, it is extremely rare to find documents of this kind.

In his article, Bauchaudy provides the decipherment of the first two original M-209 messages. Decrypting the third one was not successful and is therefore given as a challenge to the readers.

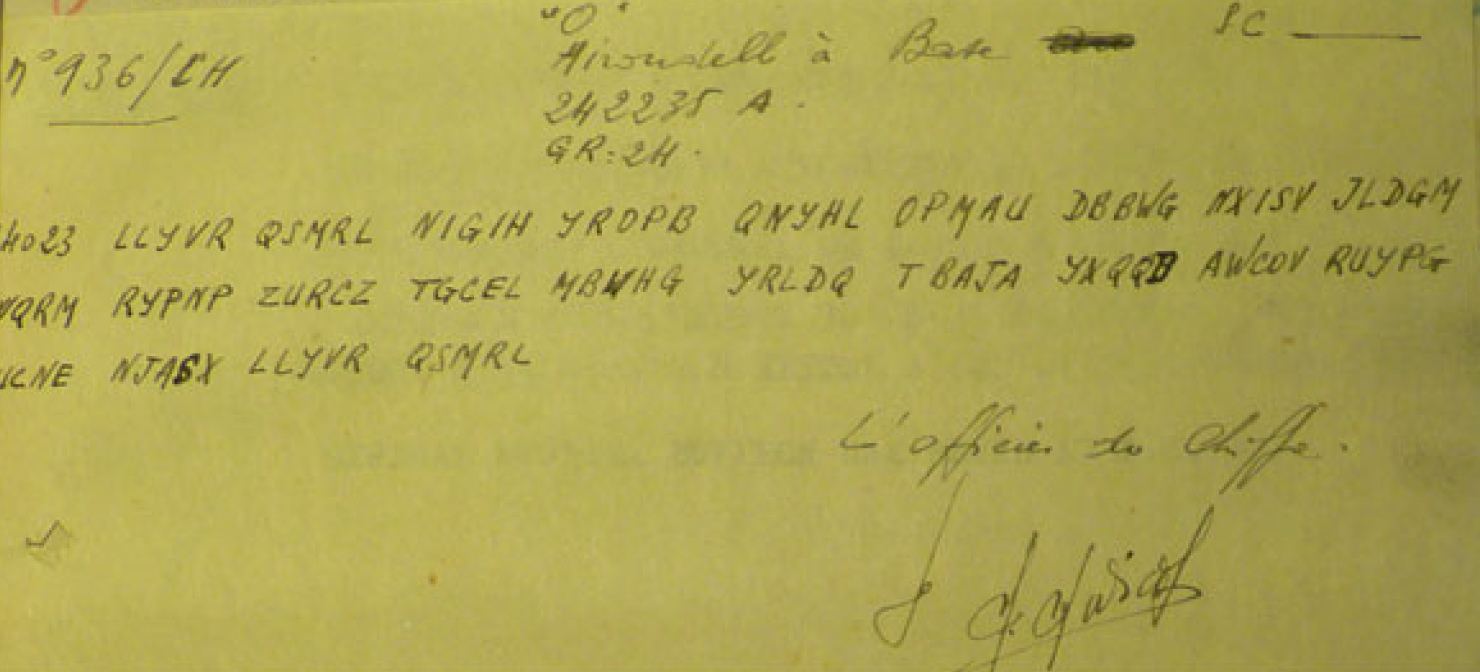

Let’s look at the first cryptogram Bauchaudy found:

Cryptologia

Here’s the plaintext, as given in the article:

NEUFTROISSIX z CH zz HIRONDELA z BASE z SP z HHH zz TTT zz

DEUXTROISKEROSEPTKERO z IIMRD z PQAPA z INDDCHIFRABLE z

L’officier du Chiffre (an illegible signature)

Spaces are represented by the letter Z (for clarity, this letter is printed in lowercase here). If a Z appears in the plaintext, it is replaced by K (for instance, ZERO is written KERO).

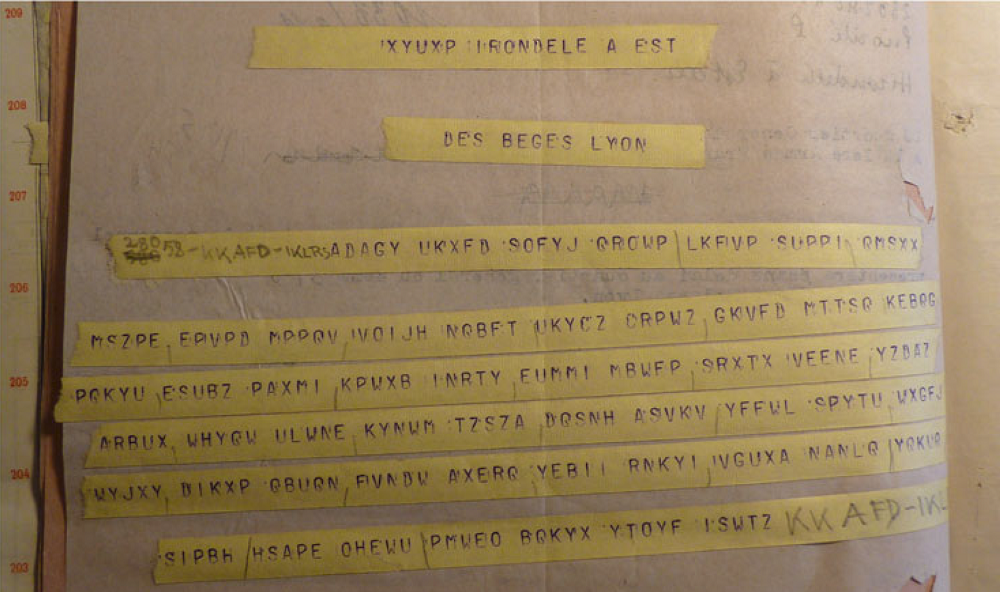

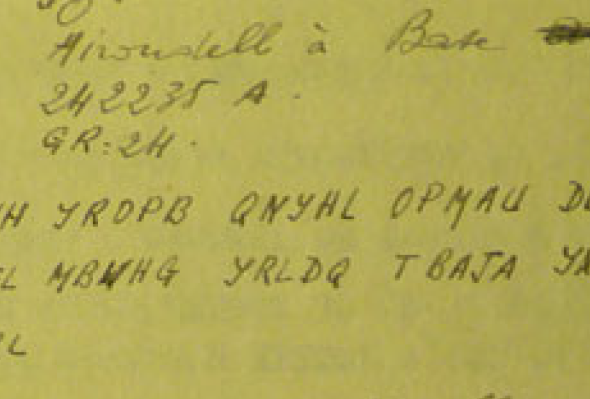

We skip the second M-209 ciphertext (if you’re interested in it, you need to read the article) and proceed to the third one (dated 28 September 1944). Here’s a scan:

Cryptologia

Bauchaudy transcribed this message as follows (the first part is in the clear):

280240A

Priorit_e P 1038/CH

Hirondelle _a Estelle

Du Quartier g_en_eral de la 7i_eme arm_ee _a la 1_ere Arm_ee Franc¸aise.

Conform_ement aux ordres rec¸ues, du 6i_eme groupes d’arm_ees, tout

le personnel du 4i_eme SFU terminera son service imm_ediatement et

se pr_esentera sans d_elai au quartier g_en_eral du 4i_eme SFU, 58

Boulevard des Belges, Lyon. 272345A

KKAFD IKLRS

XYUXP IRONDELE A EST DES BEGES LYON

28058-KKAFD-IKLRS ADAGY UKXFD SOFYJ QROWP LKFVP SUPPI QMSXX

MSZPE EPVPD MPPQV VOIJH NQBFT UKYCZ ORPWZ GKVFD MTTSQ KEBQG

PQKYU ESUBZ PAXMI KPWXB INRTY EUMMI MBWFP SRXTX VEENE YZDAZ

ARBUX WHYQW ULWNE KYNWM TZSZA DQSNH ASVKV YFFWL SPYTU WXGFJ

WYJXY DIKXP QBUQN FVNDW AXERQ YEBII RNKYI VGUXA NANLQ YQKUQ

SIPBH HSAPE OHEWU PMWEO BQKYX YTOYF ISWTZ KKAFD-IKLRS

Here’s a translation of the cleartext part:

280240A

Priority P 1038/CH

Swallow to Estelle

From the headquarters of the 7th Army to the 1st French Army. In

accordance with the orders received from the 6th Army Group, all 4th SFU

personnel will finish their service immediately and will report without delay

to the 4th SFU Headquarters, 58 Boulevard des Belges,

Lyon.

Can a reader decipher this message? It’s certainly not easy and it requires detailed knowledge about the M-209. Good luck!

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Further reading: George Lasry’s new attacks on the Geheimschreiber

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13501820

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/763282653806483/

Kommentare (2)