British author Lady Gwendolen Gascoyne-Cecil encrypted a passage in her diary. This cryptogram has never been solved.

Enrypted diaries are a fascinating topic, but they rarely make major crypto mysteries. This is because the ciphers used by diary authors are usually simple substitutions (MASCs), which are easy to solve for a skilled codebreaker. Applying a more secure encryption system is normally not an option, as complicated ciphers are too laborious for writing longer journal entries. For this reason, my encrypted book list doesn’t contain any unsolved encrypted diaries.

Nevertheless, there is at least one nice crypto mystery connected to a diary. This journal was written by Lady Gwendolen Gascoyne-Cecil (1860-1945), the daughter of British Prime Minister Robert of Salisbury (1830-1903). Besides being a member of a prominent family, the Lady’s claim to fame was a successful book she wrote about her father.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

A few years ago, blog reader Ralf Bülow kindly pointed out to me that Lady Gewndolen had left behind an interesting cryptogram in her (otherwise unencrypted) diary. The source Bülow mentioned was the German book Wilhelm II. written by historian John C. G. Röhl (check here for the corresponding passage on Google Books).

A diary entry with numbers

Lady Gwendolen wrote the diary entry in question in the year 1888, which went down in German history as the Year of Three Emperors. In her journal, she mentions a person she describes as “465113, 49359”. According to the book by Röhl, a passage with eight more number groups follow. It is not known what these encrypted passages mean. I blogged about this story in 2015 (in German), but my readers couldn’t solve the mystery.

In a comment, blog reader Richard SantaColoma remarked that the diary excerpt reproduced in Röhl’s book was incomplete. Richard found a longer (complete?) version of this text in the book Salisbury: Victorian Titan by Andrew Roberts.

Now, four years later, I would like to address Lady Gwendolen’s diary again. This time, I quote the journal entry as reproduced in Roberts’ book (hoping that this is the correct version). Here it is:

S[alisbury]’s political anxiety is enormously increased by a conversation he had with 465113, 49359 — just 54461 415211 A & 55154 — is so 39751 30939 the 62818 562412 has been 60313 that 525210 the first 62041 562412 will 47651 497316 her 52062 will be 59941 60633 and yet 546410 477316. S[alisbury] could hardly believe his ears and was still more horrified when he gathered that 535611 58955. During 443513, 41463, always 39869 39869 31763 43447 and family and 48811 seems 50458 29911. From what S[alisbury] knows 457316 434447 336318 43168 thinks 43447. 33145 497316 anything, though this 50741 34942. He does not think that 562412 63131 58453 if she 60633. Doubtful how far 43447 45147 over 44148 40012 even now, and if he should 35234 S thinks 48355 36946 incapable 497316 424219 & 47651 — 539620.

As a conclusion, Roberts writes:

Any clue as to which code was being employed has sadly not survived. Despite the best efforts of the Foreign Office Librarian, of the decrypters, GCHQ, and many kind readers of The Times’ literary pages, including Bletchley Park alumni, it has proved impossible to decipher it, owing to its shortness. Something of the sense of crisis can be deduced from the vocabulary which intersperses the numbers, however.

When Lady Gwendolen wrote this diary entry, Wilhelm I (the first of the three emperors ruling that year) had already died. His son and successor Friedrich III deceased a few months later of throat cancer. Was it the news about the serious disease of the new emperor that shocked Salisbury? This sounds like a plausible hypothesis. However, when Friedrich III took office, his suffering was no longer a secret – his illness was already so advanced that he could not speak any more.

Is the encryption solvable?

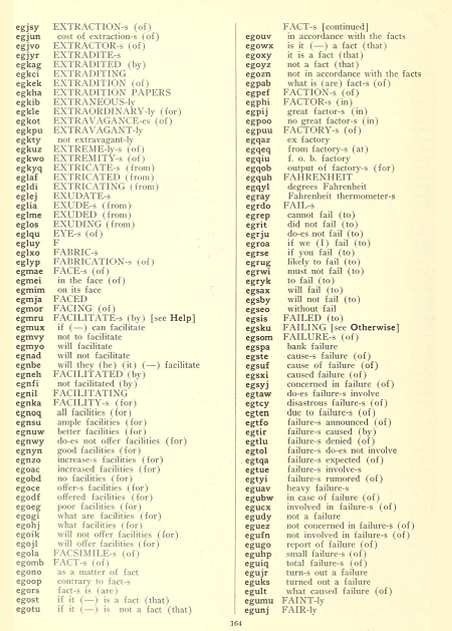

My first guess was that Lady Gwendolen had used a code for encrypting her diary entry and that the numbers represent codewords. Codebooks were a common means of encryption at that time. In addition, each number group consists of five or six digits, which is consistent with a code, too. The following scan shows a codebook page (it’s certainly not the one used by Lady Gwendolen; it contains number groups, not letter groups):

Source: Internet Archive

If the code hypothesis is correct, each number in the diary passage stands for a whole word or an expression of several words. Solving the cryptogram will probably only be possible if somebody finds the codebook.

However, after my first post adressing the Gwendolen cryptogram, blog reader Tobias Schrödel wrote that the numbers the Lady used are too high for a typical code of the late 19th century. Codebooks of this era had at most 30,000 entries, so the codegroups usually consisted of low five-digit numbers.

If Lady Gwendolen didn’t use a code, which other encryption method might she have applied? Was it a simple substitution (MASC)? In don’t think that back in 1888 a person without a military background or a special interest in ciphers used a much more complicated system. So, it seems possible that the encryption can be broken. On the other hand, there is not much ciphertext to study, which makes it difficult to attack even a simple encryption method.

If a reader can find out more, please let me know?

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Further reading:

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13501820

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/763282653806483/

Kommentare (24)