Crypto expert Frode Weierud has published a collection of unsolved cryptograms from 1969. If you’re looking for a challenging codebreaking project, here you go.

Many readers of this blog certainly know Frode Weierud. Frode, a retired software developer from Norway, has been involved with cryptology for over 50 years. As a leading Enigma expert, he is mentioned in several books I have written (especially in Nicht zu knacken) and on this blog.

Among other things, Frode has deciphered hundreds of Enigma messages from the Second World War. His homepage, Frode Weierud’s CryptoCellar, contains plenty of interesting information about the Enigma, the Kryha machine, the Lorenz machine and more.

The Biafran Ciphers

Recently, Frode has published a report about a collection of ciphertexts from the Nigerian Civil War (1967-1970), also known as the Biafran War. This war was fought between the government of Nigeria and the secessionist state of Biafra. The conflict resulted from political, economic, ethnic, cultural and religious tensions. Control over the lucrative oil production in the Niger Delta played an important role.

Frode obtained the ciphertexts (he calls them Biafran Ciphers) already in 1969. They had been transmitted by radio teletype between Biafra and Lisbon, and apparently somebody in Norway had intercepted them. Frode tried to decipher the messages, but to no avail. He thought about publishing them in a Cryptologia article in the late 1970s, but he decided not to do so, as they stemmed from a recent war and the content still could have been sensitive.

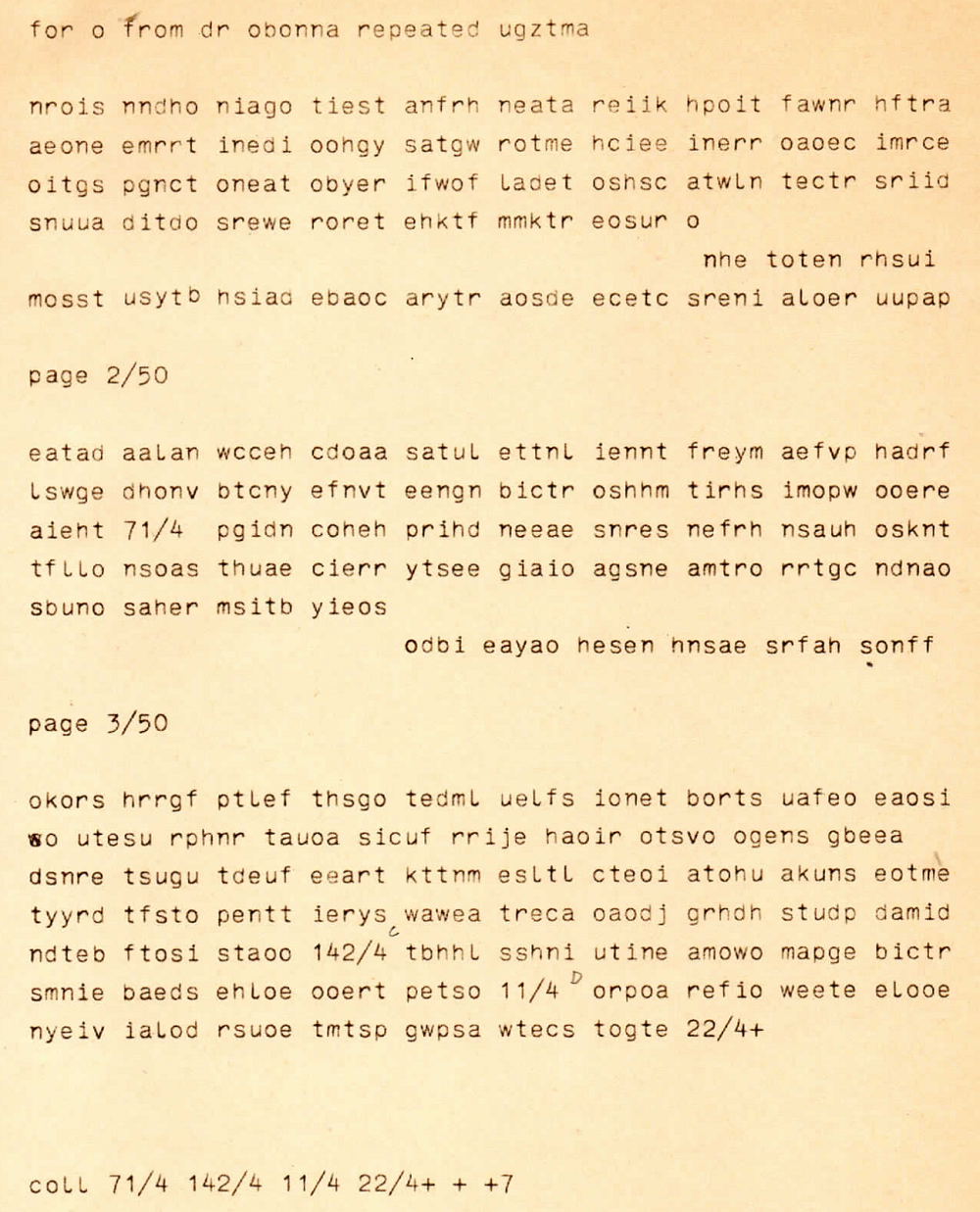

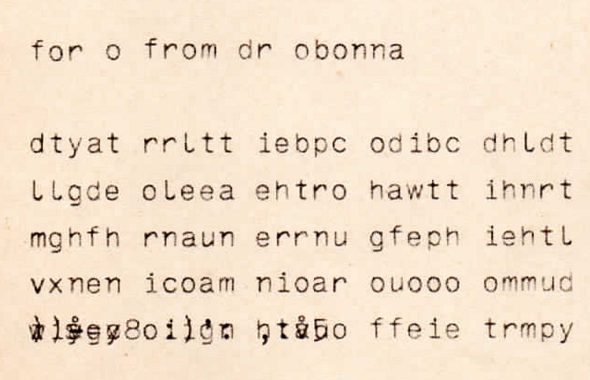

40 years later and 50 years after the messages had been intercepted, Frode thought that meanwhile it was safe to publish the messages. So, he made scans and a few transpositions available on his website. You can help Frode by transcribing messages that have not been transcribed yet.

A transposition cipher and a code?

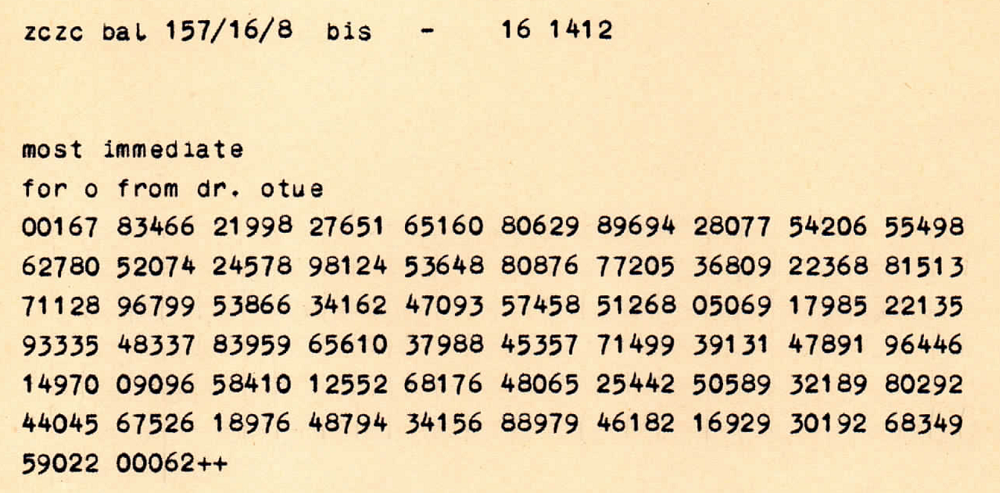

The scans are provided in some 60 PDF files. The messages were sent between August 2nd and October 21st, 1969. According to Frode, two different ciphers were used. He writes:

Source: Weierud

The ciphertexts in this collection are of two types, messages in groups of 5-letters and 5-figures. In 1969, shortly after receiving these messages, I made a quick analysis of both types of messages. A frequency analysis of the 5-letter traffic showed a monoalphabetic distribution corresponding to English plaintext, and the form of the messages made me believe that they were enciphered by a transposition system. The messages are divided into a number of blocks that often, but not always, consist of an odd number of groups. The message BAL025 from 04 August 1969 is divided into four blocks marked 71/4, 142/4, 11/4 and 22/4. The number behind the slash is the date when the message was enciphered. It therefore seems logical to believe that the same or a similar transposition is performed on each of these blocks. In 1969 and also later in 1978 a few feeble attempts were made to break into this system. Irregular columnar transposition and some other of the more common transposition systems were investigated but without any success. In the end I decided that either double transposition was used or a kind of stencil system.

Source: Weierud

The 5-figure system is most likely a code but it could also be a substitution cipher. No detailed analysis has been made of this system largely because there are so few of these messages.

Codes and transposition ciphers have both been discussed on this blog many times. Both systems are very hard to break if used properly.

To solve a transposition cryptogram, usually some trial-and-error is necessary. There are many ways to change the order of the letters in a message, some based on lines and/or columns, others based on stencils. For an example of a successful transposition cryptanalysis, check David Stein’s paper on the Kryptos inscription (the third part of the inscription is encrypted in a transposition cipher).

If the second type of encryption is based on a code, there are two common ways to solve it. First, one can hope that the code has a conceptual flaw – for instance that the code groups are sorted alphabetically. Second, one can try to find the codebook that was used. Both methods have been used successfully in the past. Good luck!

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Further reading: What happened to codebreaker Heinrich Döring after WW2?

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13501820

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/763282653806483/

Kommentare (13)