Solved: The encrypted letters from Charles I to his son

My blog readers have once again achieved a great success: Norbert Biermann, Thomas Bosbach and Mathew Brown have solved the encrypted letters of Charles I, which I presented a few weeks ago.

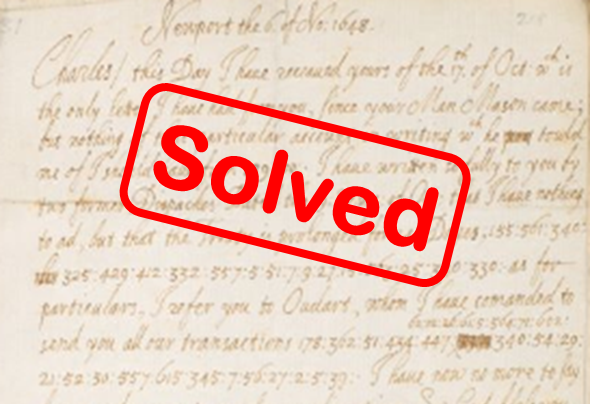

The English King Charles I (1600-1649) was imprisoned for about a year on the Isle of Wight, an island off the south coast of England, until shortly before his execution.

As you can read on Satoshi Tomokiyo’s website, he wrote several encrypted letters to his son from there. Another letter Satoshi lists was sent to the aristocrat Edward Worsley.

Norbert, Thomas and Matthew find the solution

On April 11, 2021, I presented the said letters on my blog. Norbert Biermann, whom my readers have long known as an excellent codebreaker, analyzed these cryptograms and published his intermediate results as comments to my article. Thomas Bosbach and Matthew Brown, also no strangers to this blog, joined in. When it became too cumbersome to conduct the discussion via blog comments, the three contacted each other and from then on exchanged information via e-mail.

With success: Norbert, Thomas and Matthew were able to reconstruct a nomenclator that Charles I had used for his letters. This enabled them to decode the letters of September 2, October 3, and November 6 and 7, 1648. The letters of August 1 (to the son) and May 22 (to Worsley), on the other hand, were written with a different nomenclator and therefore remain unsolved for the time being.

I need not stress that I am once again delighted. Norbert, Thomas, and Matthew have done a great thing. I am proud to be able to report about it on my blog. For this I don’t even have to suck much out of my fingers, because Norbert sent me a description of the solution that leaves nothing to be desired – even including an English translation! Thanks a lot! This makes blogging a lot of fun.

Preliminary remarks

Norbert, Thomas and Matthew write about their solution:

We are very sure about the single letter part of the nomenclator (code groups 1 through 90). Because of the nice regularity, code groups that do not even appear in the letters could also be assigned (shown in gray below).

The word part of a nomenclator, however, cannot usually be reconstructed completely unambiguously, and this is especially true when there is so little ciphertext available as here: there will always be code groups that rarely appear in the ciphertext and for which different assignments seem possible. In the worst case, a single misplaced word then can completely distort the meaning of a whole paragraph. We therefore had to weigh very carefully whether our assumptions were secure enough, while delving into the historical context as best we could. In the end, we decided on a “traffic light system”: marked in green are the words we consider to be as good as certain, while yellow are suggestions we find quite plausible, without being entirely sure. Words for which we have only a very speculative suggestion are marked in red. Historians will certainly be able to provide more clarity here.

Here is the nomenclator reconstructed by Norbert, Thomas, and Matthew:

Remarks

Here are some more comments from the three successful decipherers:

- For the spelling of some words (like “wai” instead of “way”) we have followed Charles I himself.

- 9x: One line in the letter of September 2 ends with “9” (above “uncertainty of”). We assume that a digit (x) is cut off there and that 9x is a null.

- 142 = Argyll: Archibald Campbell, 1st Marquess of Argyll, who led the so-called “kirk party” in Scotland and was the most important opponent of the “Engagers” in Scotland. Would fit well here but is pure conjecture.

- 189 = Culpeper: John Colepeper, 1st Baron Culpeper of Thoresway, who was a confidant and advisor to both Charles I and Charles II. He is mentioned by name in the cleartext of the November 7 letter, but we have no direct evidence of his being “189”.

- 278 = fleet: Prince Charles actually had a small fleet at that time (for example, see here)

- 334 = help: Here, instead of “help”, a place could be designated, which Prince Charles should head for with his fleet.

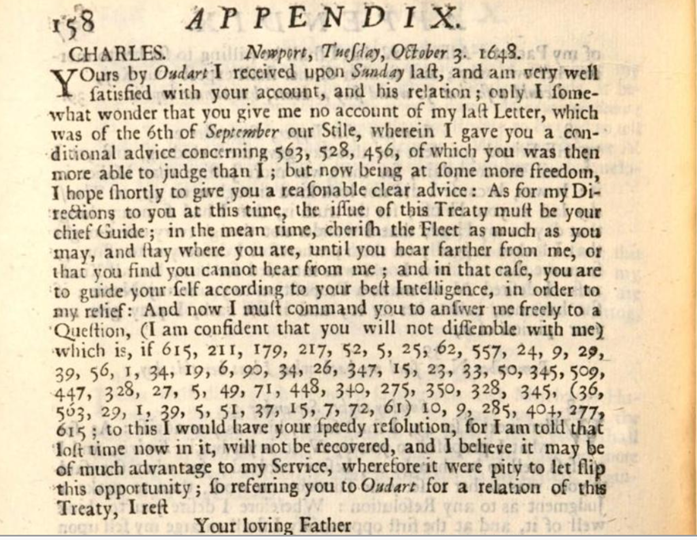

- 583 = Newport: This entry seems to be the only one that does not fit the alphabetical arrangement. However, we think it possible that Newport was listed under W along with other places located on the Isle of Wight (such as Carisbrooke Castle).

Historical background

Norbert also provided me with the following background in his email:

- 14 November 1647: Charles I, having escaped from Hampton Court, reaches the Isle of Wight. Governor Robert Hammond has him confined to Carisbrooke Castle.

- 26 December 1647: Scottish commissioners sign the so-called “Engagement” at Carisbrooke Castle, which includes a pledge of military support to Charles.

- January 1648: The English Parliament decides to end all negotiations with the King (“Vote of No Addresses”).

- Summer 1648: Prince Charles has an affair with Lucy Walter in The Hague.

- 17-19 August 1648: The Engager army is decisively defeated by Cromwell at the Battle of Preston, forcing Charles to resume negotiations with the Parliament.

- 2 September 1648: First letter from Charles from Carisbrooke Castle (with addendum of 5 Sep.).

- 18 September 1648: Treaty discussions between Parliament and King opened at Newport.

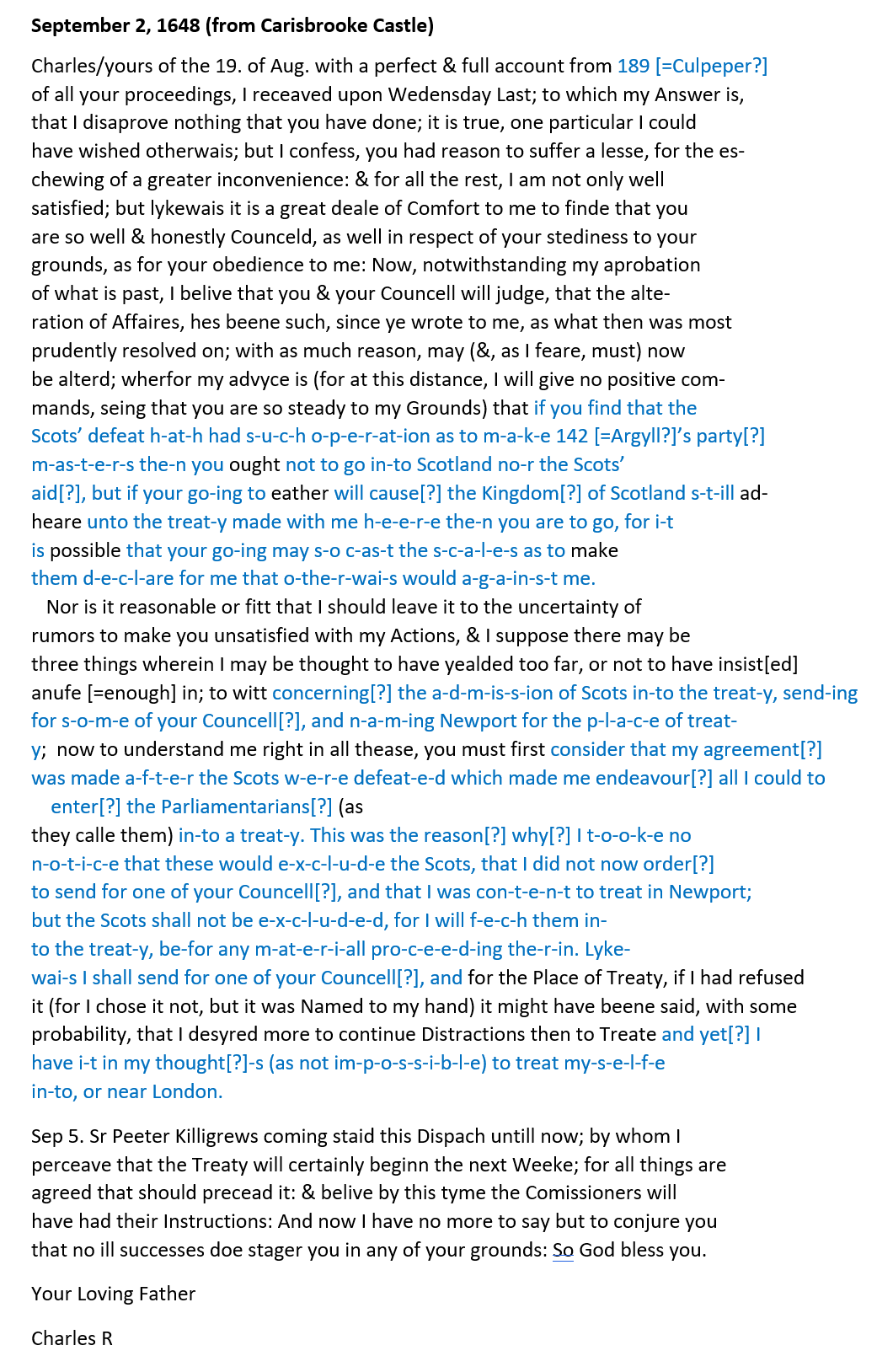

- 3 Oktober 1648: Second letter (from Newport); the news that Lucy Walters is pregnant by Prince Charles has apparently already found its way to the Isle of Wight (she will give birth to a son on April 9, 1649, immediately recognized by Charles as his child).

- 6/7 November 1648: Third and fourth letters (from Newport).

- 29 November 1648: The Newport Treaty ends.

The letters in the clear

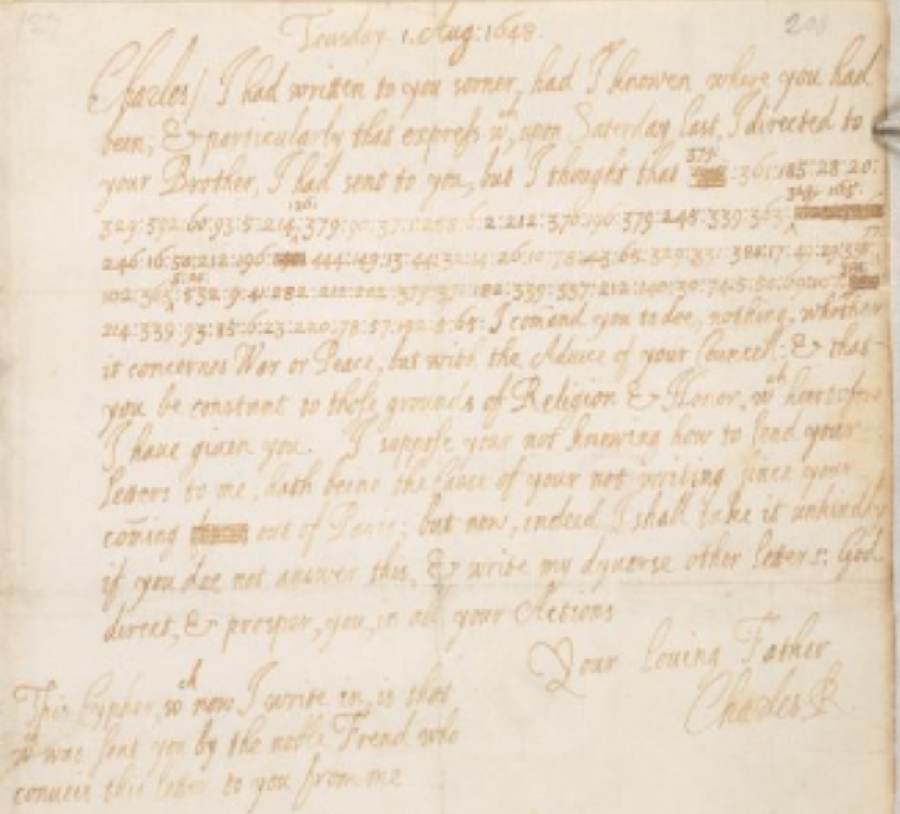

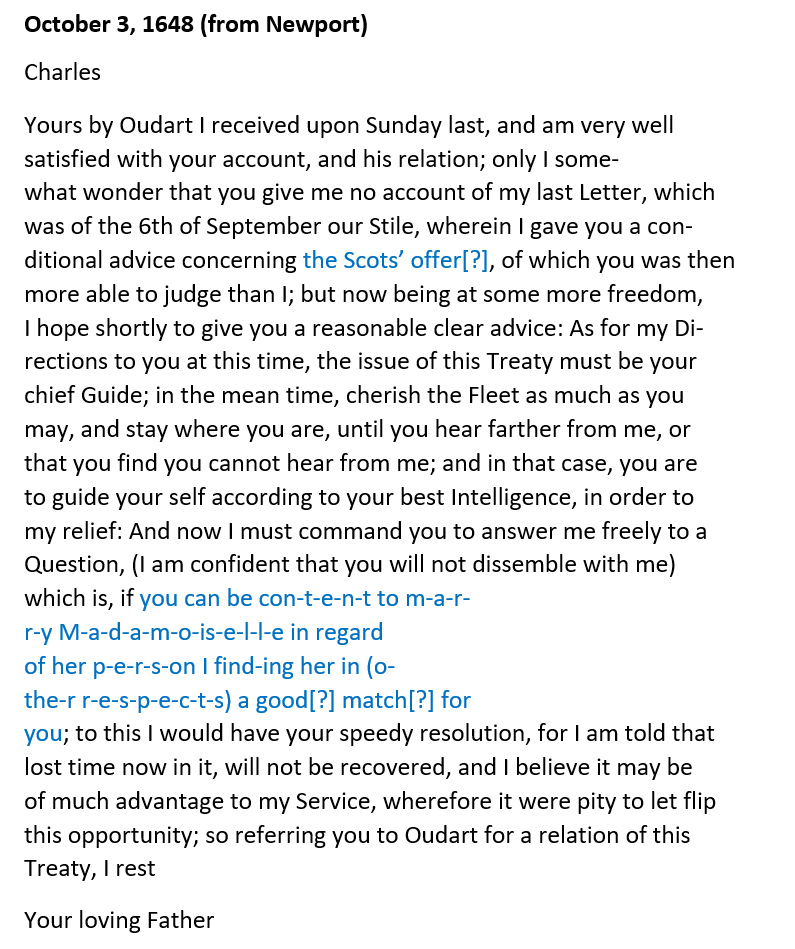

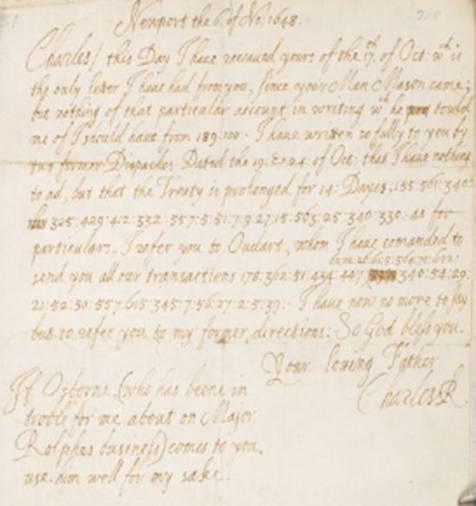

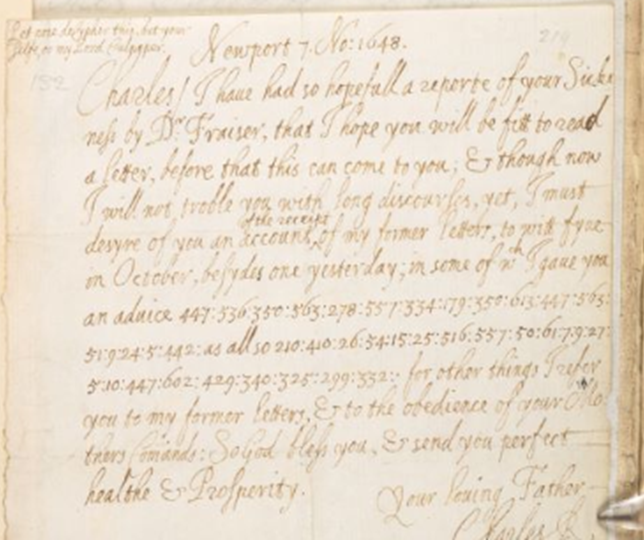

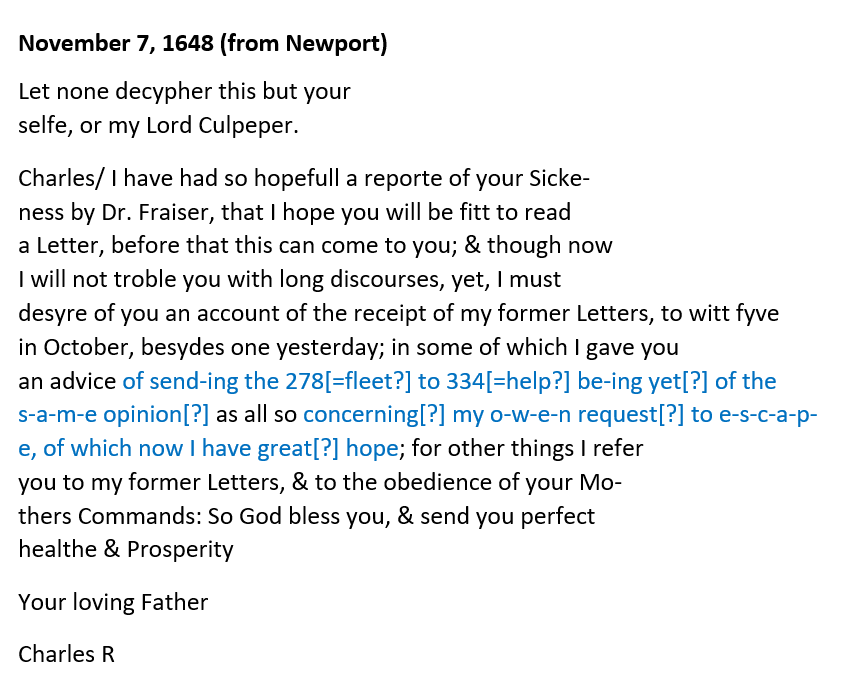

Here are the four letters with the (deciphered) ciphertext in blue. Hyphens are used to keep the encoding scheme visible (for example, Charles encodes the word “then” by two code groups, one for “the” and the other for “n”; we write the-n). “Charles R” stands for “Charles Rex”, i.e., King Charles.

2 September 1648

3 October 1648

6 November 1648

7 November 1648

Conclusion

Once again many thanks to Norbert, Thomas and Matthew for this masterpiece! I am sure that these decrypts are also interesting for historians. If you want to follow the example of these three, you can take a look at the two still undeciphered letters. Many success!

If you want to add a comment, you need to add it to the German version here.

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Further reading: The Top 50 unsolved encrypted messages: 34. Unsolved nomenclator messages

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13501820

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/763282653806483/

Letzte Kommentare