In the British National Archives I found a small codebook from World War I. Apparently, it contains a German code that was reverse-engineered by British codebreakers. Many details about the origin of this codebook are unclear.

British codebreakers played an important role in World War I. For instance, the deciphering specialists of the legendary Room 40 broke a telegram sent by German State Secretary for Foreign Affairs, Arthur Zimmermann, to Mexico, which finally convinced the US government to join the war on the side of the British.

A brief guide for crypto analysis

Last week I went to the British National Archives in London. When I searched for documents that had a relationship to cryptology, I came across a German codebook from World War I (ADM 137/4691). Described as a “Brief guide for crypto analysis”, this codebook is dated December 1916. It is available here for download.

The code described in this book is German. It was apparently used by the Germans during World War I. However, this codebook is not an original, but was reverse-engineered by British codebreakers. It is not known how the British gained knowledge of this code. Maybe a spy or a prisoner of war supported them.

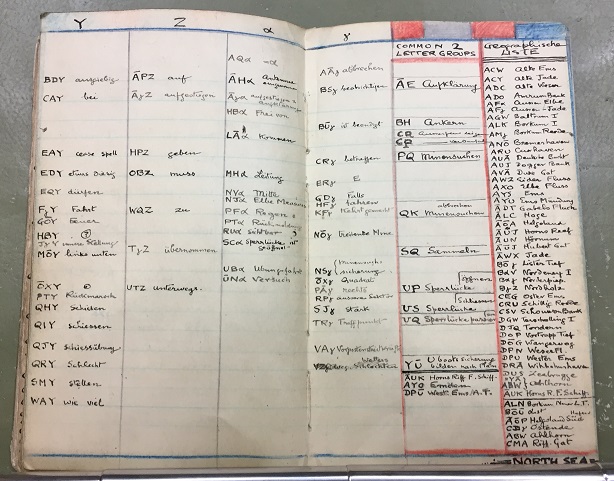

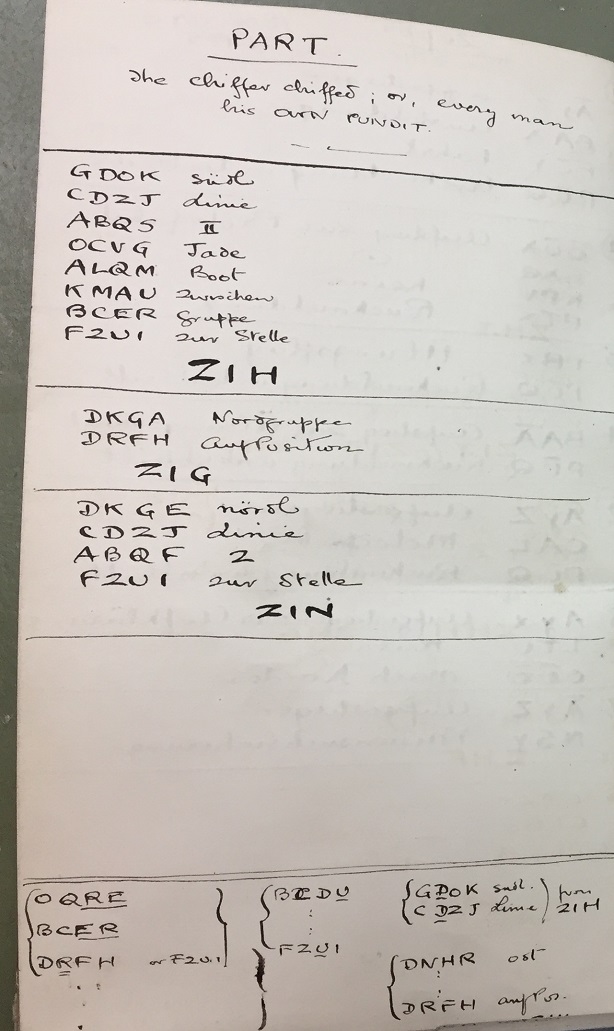

The following page is a typical one. It shows three letter codegroups standing for a German expression each:

The cleartext words, like “Kurs” (course), “aufgestiegen” (risen), and “Motorprobe” (engine test), remind me of a U-boat.

I wonder what a “Zepp” is. Does a reader have a clue?

The following page contains a number of geographic expressions (including the word “North Sea”):

Most the geographic expressions refer to places in or at the North Sea. The following page contains the cleartext word “Jade”:

The Jade is a river in northwestern Germany. It flows into the Jade Bight, a bay of the North Sea.

All in all, it is clear that this codebook was used in the North Sea area. As it is a quite simple code, it was probably not intended for the highest security level.

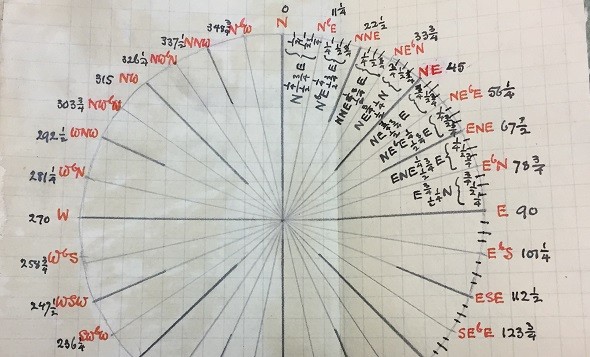

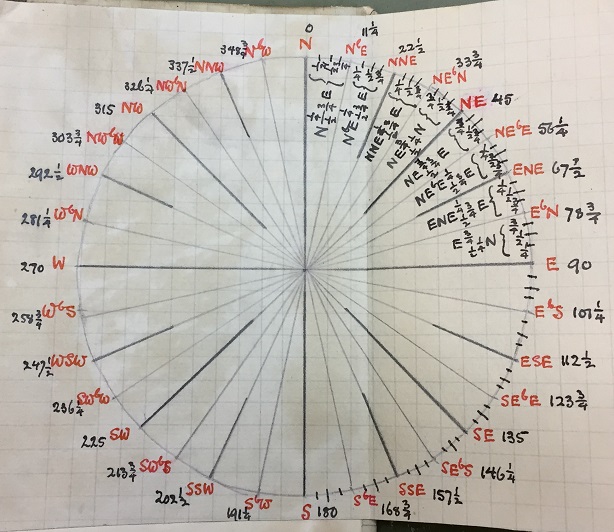

The compass diagram

The most striking page in the codebook is the last one. It shows a code expression for every compass direction:

According to this diagram, the codegroup for southwest is SW, ESE represents east-southeast. If there was no additional encryption, this part of the code was pretty weak.

If a reader can tell more about the background of this codebook, please let me know.

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Further reading: How FBI codebreakers found out what “K1, P2, CO8, K5, P2” means

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13501820

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/763282653806483/

Kommentare (18)