Many color laser printers add tiny yellow dots to each page they print. These dots encode the printer serial number and additional information. A recently published research paper reveals new information about this secret code.

14 years ago the computer magazine PC World published an article titled “Government Uses Color Laser Printer Technology to Track Documents“. According to this article, “several printer companies quietly encode the serial number and the manufacturing code of their color laser printers and color copiers on every document those machines produce.”

Yellow dots

The concept described by PC World works as follows: When a color printer (or a color copier) prints a document, it adds a pattern of tiny yellow dots (about 0.1 millimeter in diameter) to the paper. These dots are barely visible to the naked eye. The dots encode a message, which includes an identification of the printer as well as the date and time of the printing process. This means: If one knows the code, one can easily determine the origin of a printout just by looking at it.

The yellow dot code, also known as Machine Identification Code (MIC), has been around for about 25 years. As it seems, different printer manufacturers use different dot codes. In the years after the PC World article, members of the Electronic Frontier Foundation and others examined Machine Identification Codes and found out a few details about them. However, neither a printer producer nor a state authority has ever published any substancial information about this concept.

Machine Identification Codes are not to be confused with digital water marks on banknotes, which allow photocopy machines and graphics editors to detect and refuse copying of bank notes.

According to press reports, whistleblower Reality Winner, an employee of a US military contractor who leaked classified data via the platform The Intercept, was caught because law enforcement used the yellow dots code to identify the printer she had used to print out the material she was going to leak.

Last year I wrote two blog posts about Machine Identification Codes. My latest book Versteckte Botschaften (2nd edition) contains a chapter about this subject, too. Virtually all the information I found about Machine Identification Codes was over ten years old. There has not been much media coverage in the last decade, apart from the Reality Winner case.

A few days ago, reports about a method that overprints the yellow dots and thus makes the code unusuable hit the media. The method was developed by researchers of the University of Dresden, Germany.

Peter Buck’s thesis

Earlier this week, Peter Buck from Enschede, Netherlands, …

… informed me that a research work about the yellow dots code he wrote is now finished and available for download.

In my view, this 30 pages paper (it is referred to as “dissertation”, which is a little confusing for Germans, as a dissertation in Germany usually is a PHD thesis) is the most important work about the yellow dots code that has been published in recent years.

According to Peter’s paper, there are two different methods that can be used to make the dots visible:

- With the first method method (physical), the paper is illuminated with a blue light. This light makes the yellow dots appear black. These dots can then be observed using a magnifying glass. The physical method is useful for an immediate analysis of a document because it can be used at a crime scene.

- The second method is digital. Scanning a document with specific settings can make the yellow dots visible. Essential settings are DPI, sharpness, darkness and contrast. Furthermore, the scanner must use limited compression. Some imaging tools can change the color channels of an image. Deleting both the green and red channels results in a grayscale image of the blue channel. This grayscale image then shows the dots.

One of Peter’s research results refers to the code used by Xerox (until recently, the only Machine Identification Code that was understood):

Column 10 was previously thought to be a separator between the serial number and the date and time of printing. As Peter found out, it is instead a line which defines whether a document has been printed or copied. If column 10 is filled, the document is printed. If it is empty, except the parity bit, the document is copied.

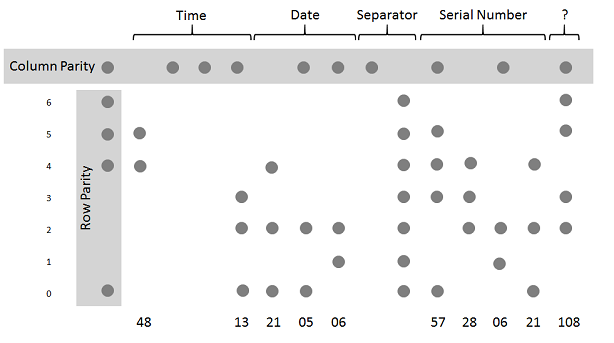

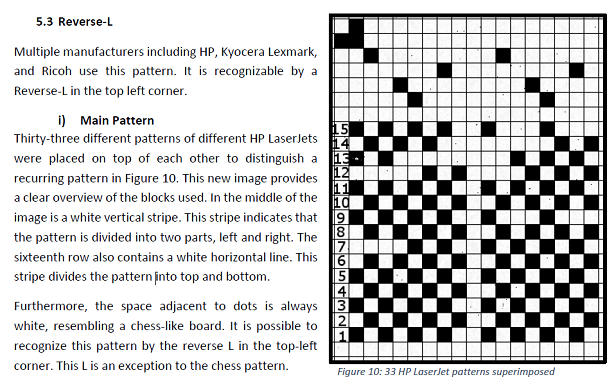

Peter’s main research result is the decoding of another code, used by HP, Kyocera Lexmark, and Ricoh.

This code, which encodes the time of printing, as well as the printer type and some other information, is described on pages 13-16 in Peter’s publication.

Congratulations, Peter, on this great work. I hope, we will see more research of this kind.

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Further reading: My steganographic gravestone tour (2): The “Fuck You” gravestone in Montreal

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13501820

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/763282653806483/

Kommentare (7)