In the 1920s, a textiles expert developed a code for transmitting information about clothing by telegram. He even received a patent for this invention.

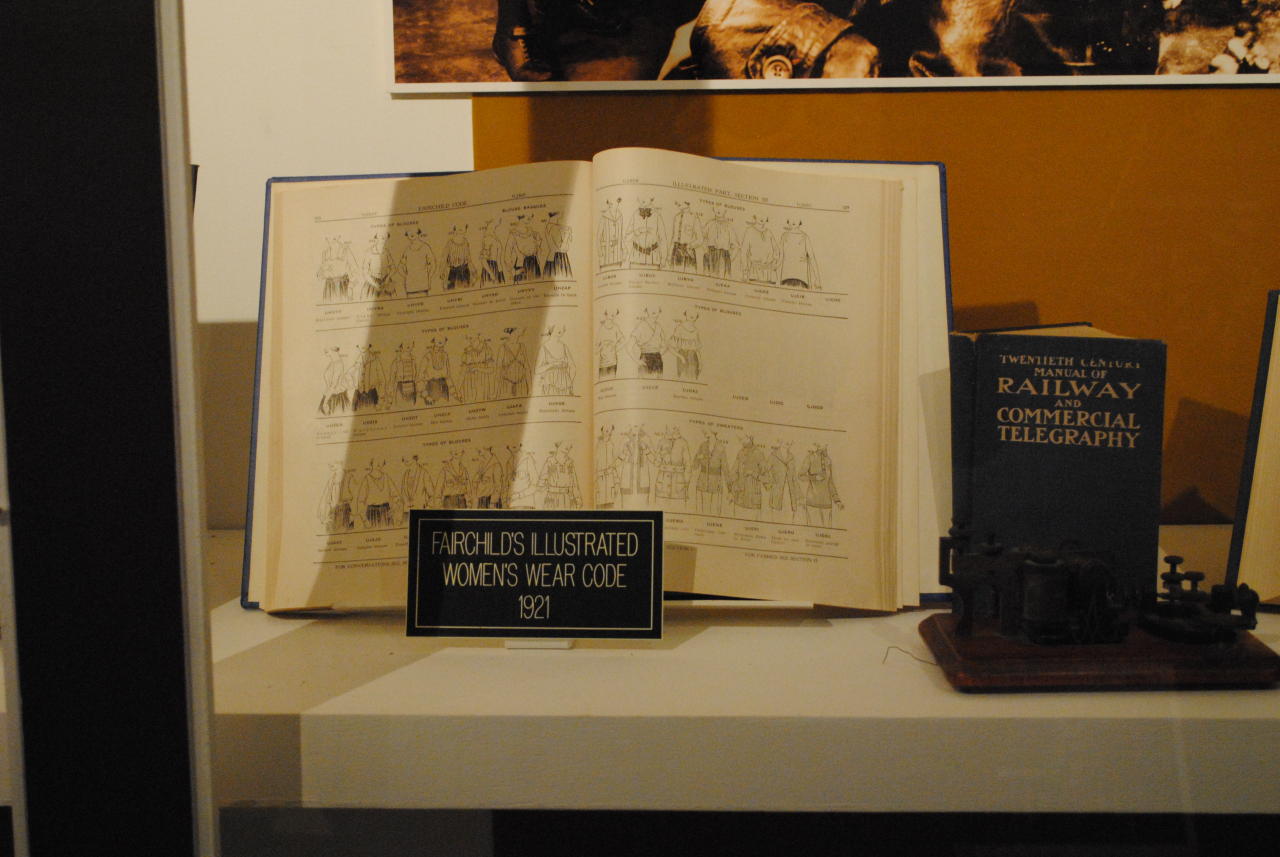

The National Cryptologic Museum in Fort Meade near Washington, DC, owns hundreds of codebooks. Here is an especially interesting one:

As can be seen, this codebook depicts fashion pictures. It reminded me of the hidden messages in fashion pictures that are mentioned in a WW2 censorship broshure I have mentioned on this blog several times:

Was this codebook the answer to the still unsolved question how the steganographic code used in these fashion drawings works? Was this codebook used by spies to camouflage their spy reports as fashion drawings?

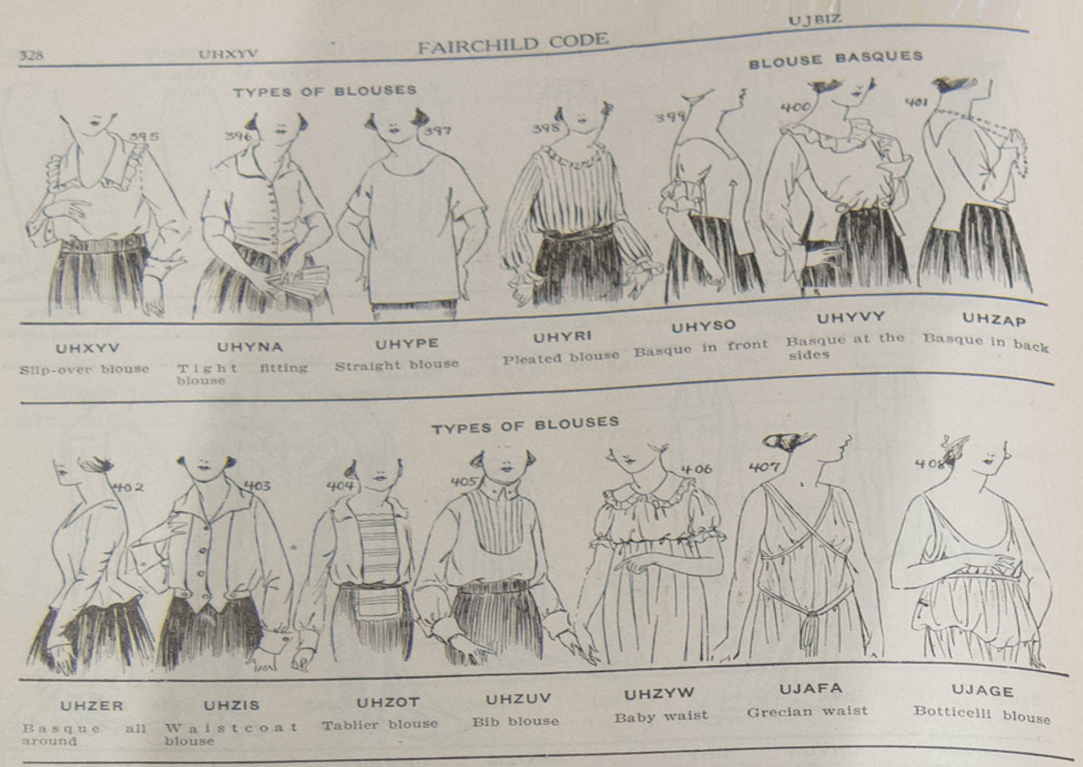

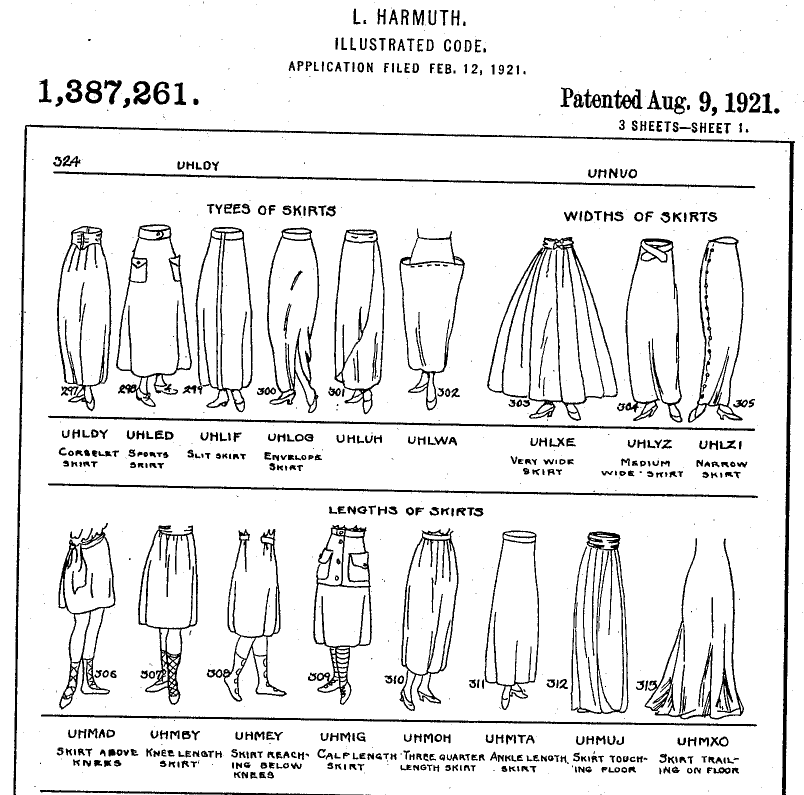

The answer is no. The codebook displayed in the museum (Fairchild’s Illustrated Women’s Wear Code from 1921) had nothing to do with steganography or espionage. Instead, it was meant to encode all kinds of clothing types in five letter groups that could be easily sent by telegram. For instance, the following excerpt shows different types of blouses, along with their code representations:

If a retail store wanted to order, say, 20 red bib blouses, it simply sent the message “20 RED UHZUV” to the supplier. As telegrams were usually charged by the number of words, it is clear that such a code saved money. Of course, the encoding was also a kind of encryption, as the meaning of expressions like UJAGE or UHZER was not known to everybody. If a high degree of security was desired, an additional encryption could be applied (e.g., by interpreting the letters as a number and by adding a key number to it).

Check here for a larger scan of a page from this codebook.

Apparently, the creator of this codebook (a certain Louis Harmuth, who also wrote the Dictionary of Textiles) wanted to prevent his competitors from copying this concept. This is proven by the following entry in the Catalog of Copyright Entries:

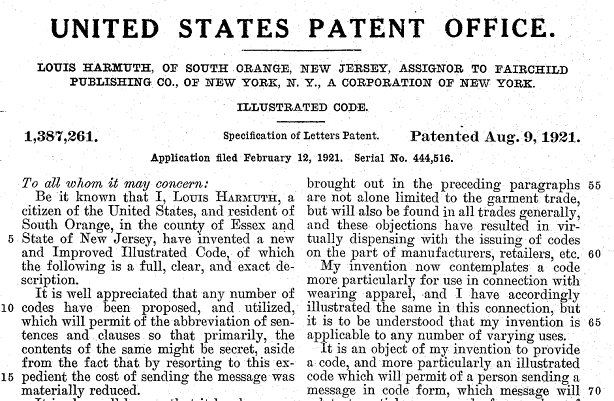

Louis Harmuth also filed a patent for an “Illustrated Code”.

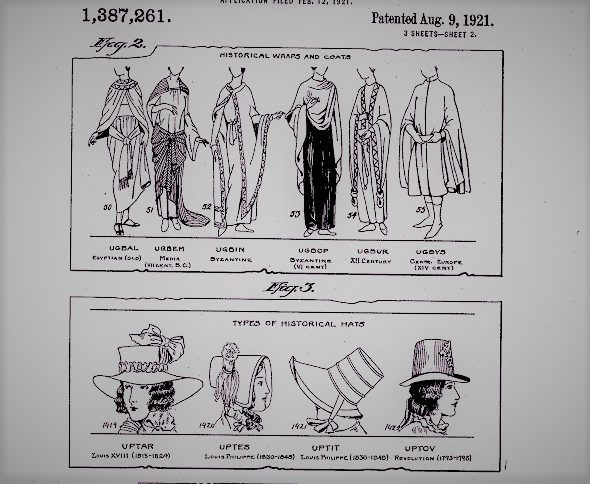

Here is an illustration from his patent:

Interestingly, the codebook only refers to women’s wear, while the patent doesn’t say anything about gender. On the other hand, all the illustrations in the patent depict women’s wear only. The reason probably is that Louis Harmuth was specialized on women’s wear. He even was the editor of a magazine named Women’s Wear, as can be read in the dictionary he wrote.

Harmuth’s textile codebook is an interesting document from a time when telegraphy was an important means of business communication and when encoding information such that it could be transmitted by telegram was an important issue. With the advent of fax, email and other communication technology codes like these became obsolete.

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Further reading: A reverse-engineered codebook from World War I

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13501820

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/763282653806483/

Kommentare (1)