George Lasry has found an interesting collection of challenge ciphers, probably used to train codebreakers during the early Cold War. Today, I’m going to present one of these challenges.

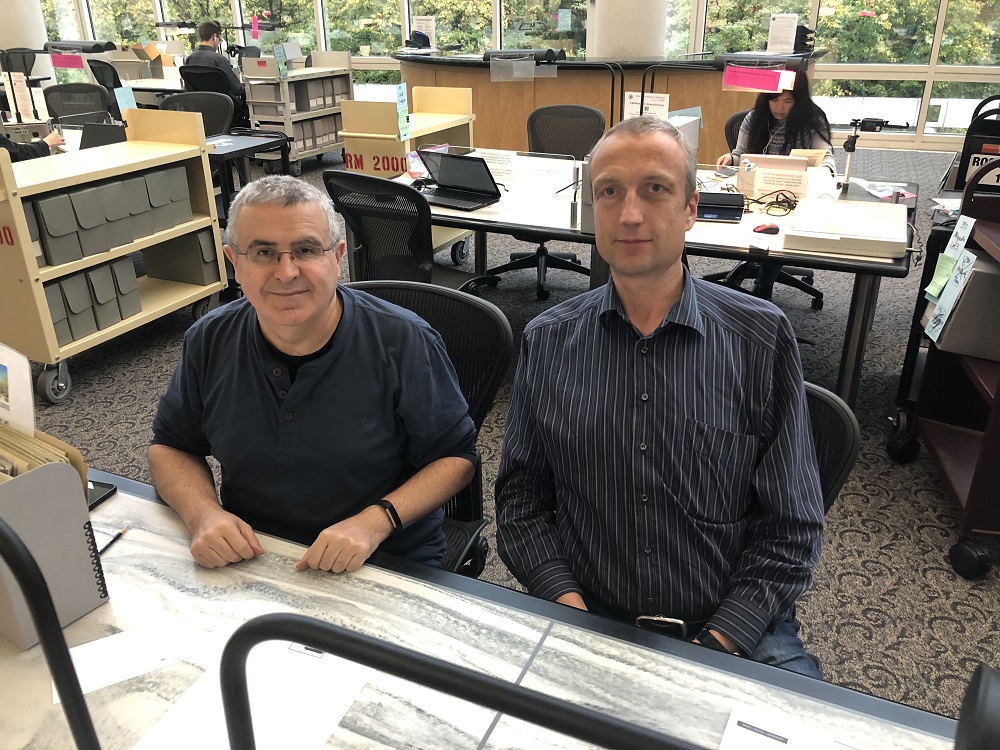

Two weeks ago, on the day before the NSA Symposium on Cryptologic History started, I went to the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in College Park near Washington, D.C. Together with Israeli codebreaker George Lasry …

Source: Klaus Schmeh

… I combed through thousands of documents related to cryptography, mainly from the Second World War and the early Cold War. We found a lot of interesting stuff, including information about US encryption machines George can use for his research work. We spent an interesting day at NARA, but it was also exhausting to deal with such a huge amount of information.

Of course, George knows that I’m always looking for historical cryptograms I can publish on my blog. While he was skimming through one of the files he had ordered, he said: “I have found something interesting for you. This might provide enough material to write about on your blog for a whole year.”

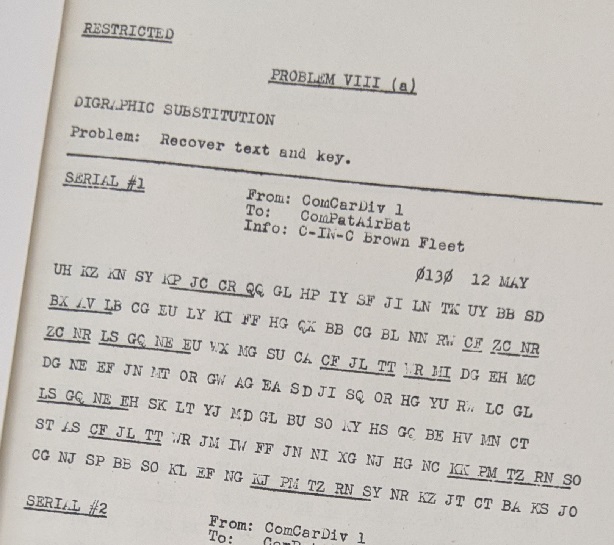

What George had discovered was a collection of challenge ciphers, probably from the Cold War. Unfortunately, the file was not properly labeled, so we don’t know exactly where these ciphertexts come from. Apparently, they were used for training US cryptologists, approximately in the 1950s.

The collection consists of several dozens of cipher problems, starting with MASCs (monoalphabetical substitutions), then getting more and more difficult. Among others, polyalphabetic and turing grille cryptograms are contained. The solutions are not provided.

A bigram substitution

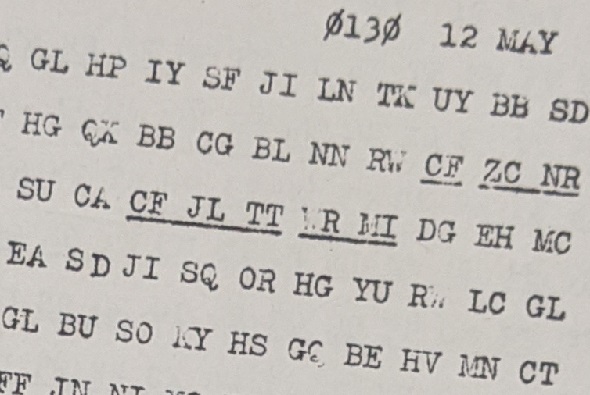

Some of the challenges George found are headlined “Digraphic Substitution”. The first one (problem VIIIa) is reproduced in the following.

A digraphic substitution (also known as bigram substitution) replaces letter pairs. There are numerous variants of this method, but only two of these have found widespread use:

- The general bigram substitution is based on a table that provides a replacement (usually another bigram) for every existing bigram. If we are dealing with an alphabet of 26 letters, such a table has 676 columns. The shortest general bigram ciphertext ever broken has 1000 letters. This record was set by Jarl Van Eycke and Louie Helm only a few days ago.

- The Playfair cipher is defined by a set of simple rules. It is much easier to handle than a general bigram substitution, but less secure. The shortest Playfair cryptogram ever solved (not counting a few special cases) consists of 30 letters. This record was set by Magnus Eckhall earlier this year.

Considering that problem VIIIa has some 250 letters, it is unlikely that it was created with a general bigram substitution (at least, if we assume that it is meant to be solvable). So, my guess is that a Playfair cipher was used. However, this is only a guess, other options (i.e., less popular bigram substitutions) are possible, as well.

Can a reader find out which method was used to encrypt this ciphertext? And can somebody decipher it? If so, please let us know.

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Further reading: A cryptographic challenge from the German TV show “TV total”

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13501820

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/763282653806483/

Kommentare (12)