Einem französischen Archäologen ist es gelungen, eine Schrift aus der Bronzezeit zu lösen. Blog-Leser George Lasry erklärt, wie dieser Erfolg zustande gekommen ist.

English version (translated with DeepL)

Wenn es um die Kryptologie und ihre Geschichte geht, kommt früher oder später auch die Frage nach dem Entschlüsseln alter Schriften auf. Bekannt ist vor allem die Geschichte von Jean-François Champollion, dem es im frühen 18. Jahrhundert gelang, die ägyptischen Hieroglyphen zu enträtseln. Auch das Entschlüsseln der in Griechenland verwendeten Linearschift B wird in vielen populärwissenschaftlichen Werken gewürdigt. Die wohl bekannteste noch ungelöste Schrift ist die Linearschrift A, die ebenfalls aus Griechenland stammt.

Die elamische Strichschrift

Zugegebenermaßen habe ich mich nie allzu sehr für alte Schriften und deren Enträtselung interessiert. Alte Schriften sind nun einmal keine Kryptologie, da sie nicht der Geheimhaltung dienten, und fallen daher nicht in das Wissensgebiet, in dem ich mich auskenne. In meinen Büchern zur Kryptologie-Geschichte – beispielsweise “Codeknacker gegen Codemacher” – finden sich daher keine Kapitel zu alten Schriften, während andere Krypto-Autoren (beispielsweise David Kahn und Simon Singh) dieses Thema durchaus behandeln.

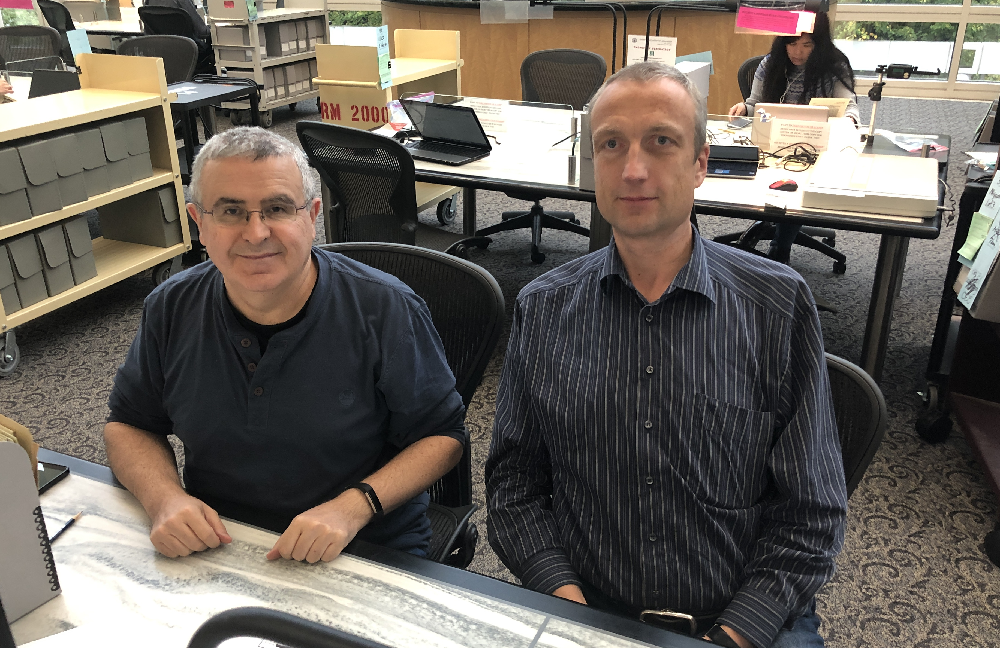

Als vor einigen Tagen durch die Presse ging, dass ein französischer Archäologe die bisher ungelöste “elamische Strichschrift” aus der Bronzezeit enträtselt hat (danke an mehrere Leser für Hinweise darauf), hatte ich aus den genannten Gründen zunächst nicht vor, darüber zu bloggen. Doch dann erhielt ich eine Mail von Blog-Leser George Lasry, der mir anbot, eine kurze Zusammenfassung für meinen Blog zu schreiben. Natürlich sagte ich zu.

George ist vielen Cipherbrain-Lesern als Codeknacker von Weltruf bekannt. Vor zwei Wochen konnte ich über 21 Dokumente berichten, die er mal eben dechiffriert hat. Seitdem hat er einige weitere Verschlüsselungen geknackt, ist aber noch nicht dazu gekommen, etwas darüber zu veröffentlichen.

Ich kannte George zunächst als Spezialisten für das Lösen von Verschlüsselungen, bei denen das Verfahren bekannt ist, der Schlüssel jedoch noch gefunden werden muss. Die Doppelwürfel-Challenge, die er vor Jahren gelöst hat, ist ein spektakuläres Beispiel dafür. Inzwischen hat sich George auch einen Namen im Knacken von Nomenklator- und Codebuch-Verschlüsselungen gemacht. Dies ist äußerst erfreulich, denn obwohl diese Form des Verschlüsselns über Jahrhunderte hinweg äußerst populär war, gab es bis vor einigen Jahren niemanden, der als Spezialist für das Lösen solcher Verfahren gelten konnte. Dank George hat sich das nun geändert, und da in den Archiven vermutlich noch Zehntausende von Kryptogrammen dieser Art schlummern, wird ihm die Arbeit nicht ausgehen.

Georges Bericht über die elamische Strichschrift

Kommen wir zum Bericht, den George mir zur Entschlüsselung der elamischen Strichschrift geschickt hat (deutschsprachige Leser mögen verzeihen, dass ich den Text nicht aus dem Englischen übersetzt habe):

Francois Desset, a French archeologist, and his team have recently succeeded in deciphering one of the oldest ancient scripts, Linear Elamite. This achievement is considered on the same level as the decipherment of Linear B by Michael Ventris in the 1950s. Some even compare it to Champollion’s decipherment of the Egyptian hieroglyphs in the 19th century.

Elam was a civilization – mentioned in the Bible – with inscriptions first recorded around 3200 BC, in scripts called Proto-Elamite (from 3200 to 2500 BC) and Linear Elamite (2300-1800 BC). Those inscriptions are contemporary with early Egyptian hieroglyphs and Summerite cuneiform writings, the cuneiform script superseding the early Elamite scripts from around 2000 BC.

Together with the famous script of the Hindus Valley – in today’s Pakistan – originating from around 2500 BC and the much later Linear A (found in Greece), the early Elamite scripts were considered among the most famous unsolved ancient scripts and the most challenging ones for experts trying to decipher them.

Deciphering an ancient script, on the surface, shares some common attributes with breaking a code. But the former is much harder if the language behind the script is unknown. Cryptanalysis techniques are irrelevant, and Desset also claims that the use of computers is worthless, and what is needed is a deep understanding of the historical civilizations and ancient languages, perseverance, and a lot of luck.

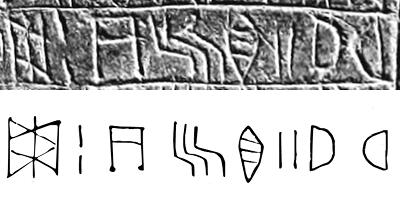

Linear Elamite has eluded experts for centuries. Before Desset’s research, only a few symbols had been phonetically identified after locating names of kings in inscriptions and then comparing them with the phonetics of those names in cuneiform writings. However, many of those identifications were wrong, there were no bilingual texts available (such as the Rosetta Stone for Egyptian hieroglyphs), and only a small number of inscriptions were found, often in a bad state.

After considerable effort. Desset was able to access new inscriptions found in a private collection. He could not find any bilingual texts, but he made progress after looking for cuneiform texts that may contain not the same text as in the Linear Elamite inscriptions but some text with similar subjects mentioning the same Elamite kings. After extensive trial-and-error, Desset could find some parallels between some cuneiform texts and Linear Elamite inscriptions, and thus recover most of the Linear Elamite symbols.

Desset’s discovery also had an enormous impact on knowledge of the history of writing. Egyptian hieroglyphs and cuneiform scripts were mostly logographic, meaning that each symbol represents an object or an entity. As a result, hundreds of symbols were needed to express all the words in those scripts. Over the years, those scripts started to have some phonetic elements, but the earliest known fully phonetic script, the Phoenician alphabet, from which the Hebrew, the Greek, and later European alphabets evolved, was from around 1000BC.

Surprisingly, the Linear Elamic script was found to be phonetic (symbols representing sounds, e.g., syllables), pushing back the earliest known phonetic script by more than 1000 years, from around 1200BC to 2300BC.

For more details:

- An accessible write-up for a general audience on this discovery, see this.

- There is also a youtube video, also for a general audience.

- A scholarly paper which is too readable to non-experts was published very recently.

Natürlich möchte ich mich an dieser Stelle noch einmal herzlich bei George bedanken. Dank seiner Unterstützung konnte ich meinen Lesern ein interessantes Thema präsentieren, auf das ich sonst wohl nicht eingegangen wäre.

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Further reading: George Lasry ist der neue Träger des Friedman-Rings

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13501820

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/763282653806483/

Kommentare (4)