CRAQUEREZ, SAUKNOTEN, INCLEMENTE – these are three words from an encrypted message sent from Manila to Washington in 1898. Can a reader break this cryptogram?

The NSA Symposium on Cryptologic History (October 19-20, 2017) was a great event with many interesting presentations given. Videos of my two talks (Cold War cryptography and Steganography in WW1) are available on YouTube.

On the day after the symposium I went to the National Cryptologic Museum, which is known as the most important crypto museum in the world. Apart from an outstanding cipher machine collection, this museum features a gift shop, …

… as well as a cryptology library and an archive.

While I was looking out for rare crypto books in the museum’s library, my friends an blog readers George Lasry and Nils Kopal worked their way through the archive – a tough job, considering that the museum owns thousands of files containing literally tons of crypto-related material.

The Manila cryptogram

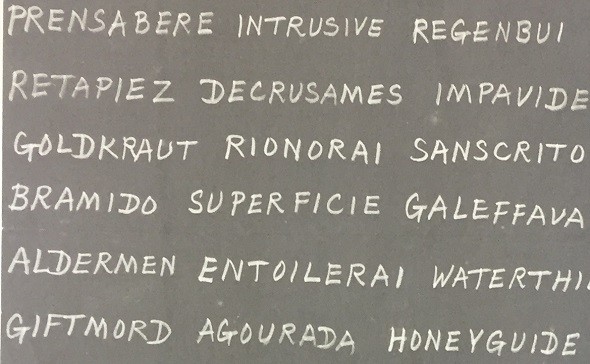

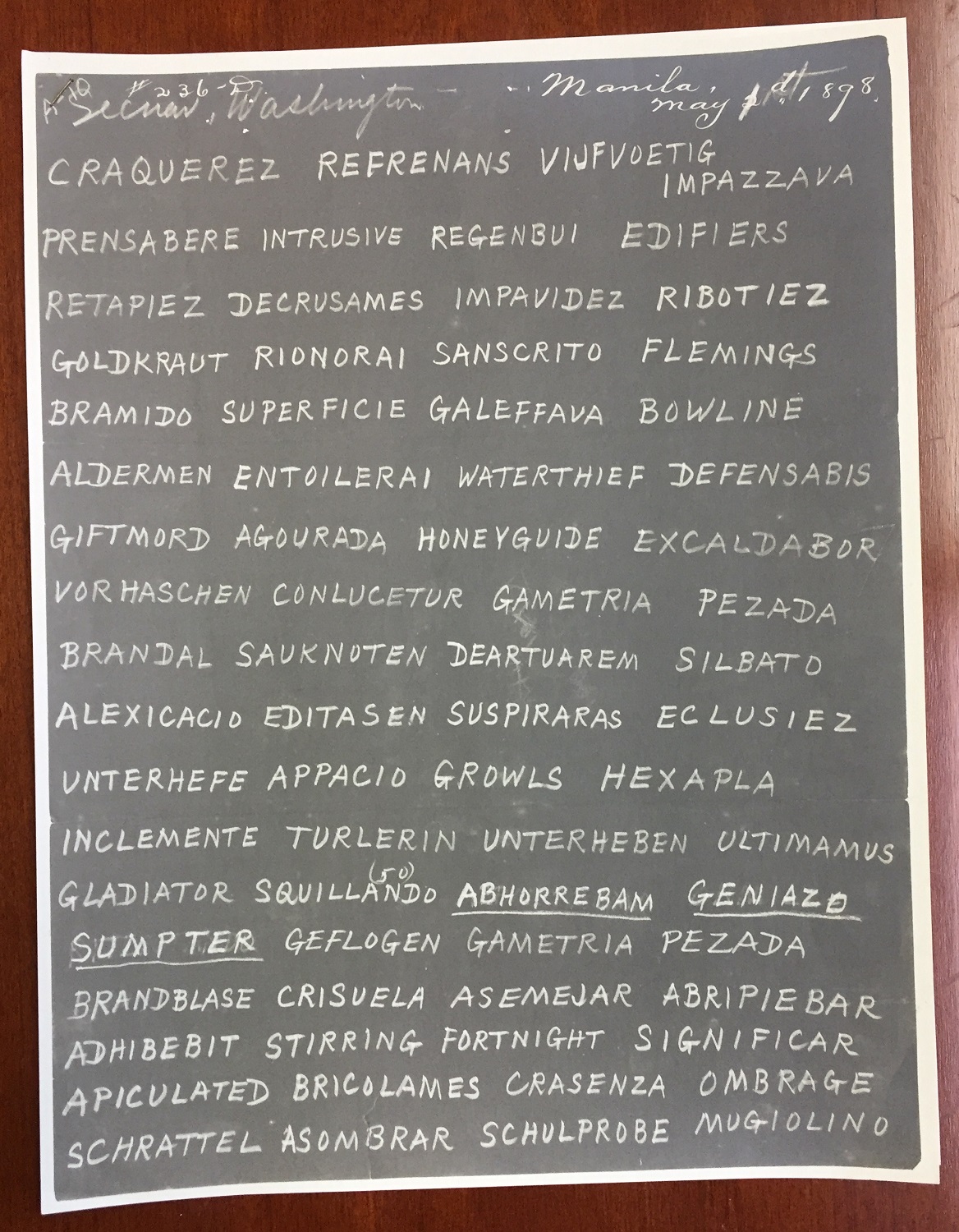

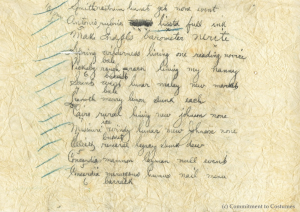

Some of the material George and Nils encountered proved to be not very relevant for them, but pretty interesting for me and my blog. Especially, an encrypted message contained in a collection of documents donated by crypto history legend David Kahn immediately caught my attention (thanks to George and Nils for informing me about it). Here’s the first page of this message:

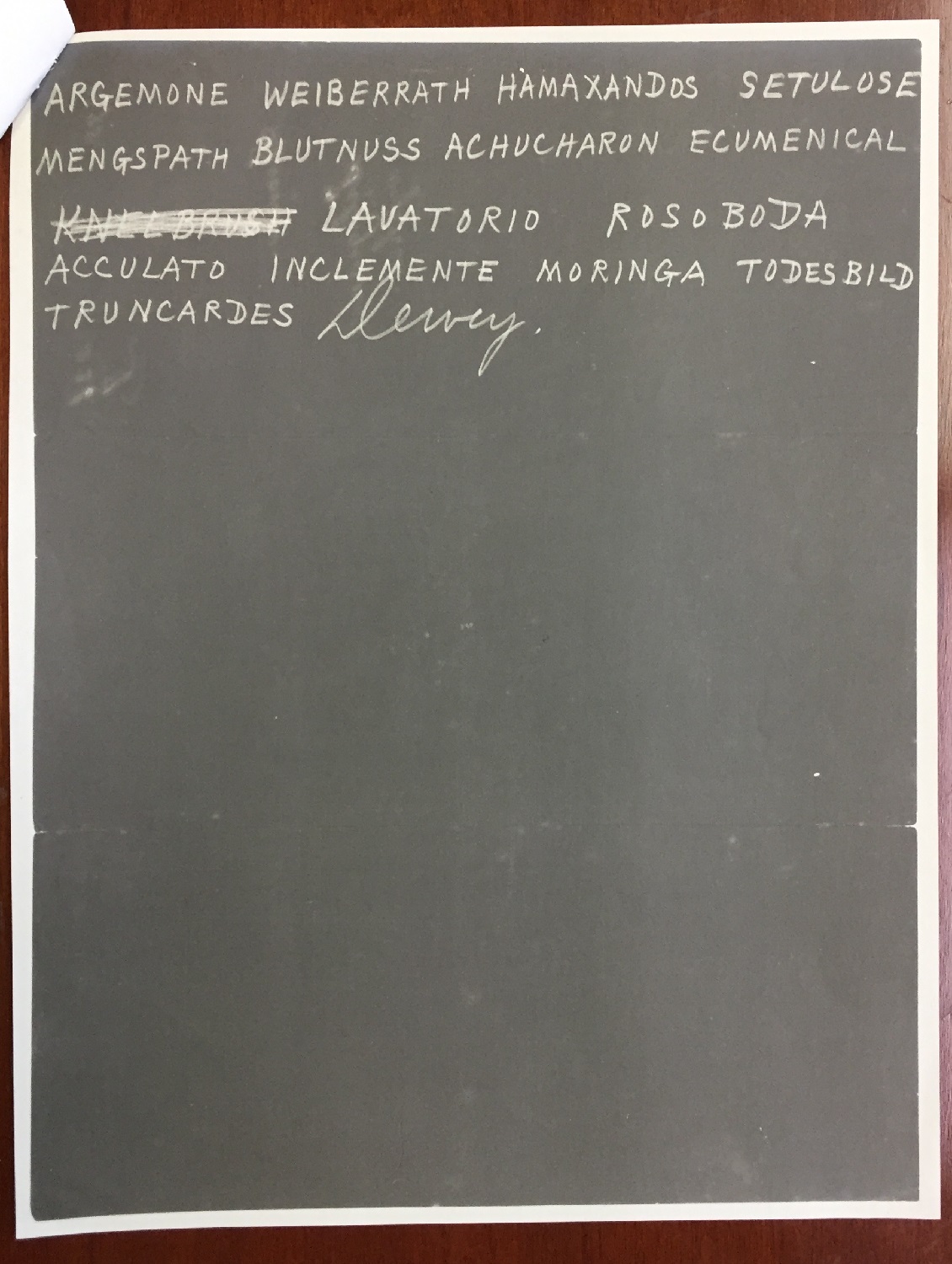

Here’s page 2:

Apparently, this message was sent from Manila, Philippines, to Washington, DC, in 1898 (I will refer to it as the “Manila cryptogram”). My guess is that it was sent by telegram.

It is immediately clear that the Manila cryptogram was not created with a letter substitution. This can be seen from the fact that all the words are pronouncable or even have a meaning. Most of them look Spanish, French or English. Some are German, including SAUKNOTEN, BLUTNUSS, SCHRATTEL, SCHULPROBE, WEIBERRATH and GOLDKRAUT. However, none of these words makes immedeate sense.

Encrypted with a codebook?

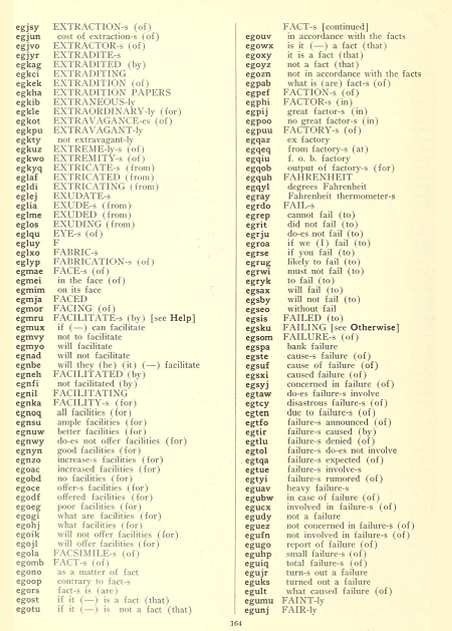

It is not very hard to guess what kind of cipher method the sender of the Manila cryptogram used. Apparently, he worked with a codebook (i.e. a book that provides a codeword or codenumber for every common word of a language). The following picture shows a codebook page:

In this case the codewords are five letter groups. Other codebooks provide pronounceable words. For instance, the silkdress cryptogram, which was probably created at about the same time as the Manila cryptogram (and is unsolved, too), contains codewords like “Vicksburg”, “Cairo”, “Calgary”, and “Concordia”.

The easiest way to solve a codebook cryptogram usually is finding the codebook and using it to decrypt the message. Without having the codebook, breaking such a message is very difficult, if not impossible, unless one has a large number of messages written in this code to analyze.

Can a reader help to find the codebook that was used to encrypt the message from Manila? If not, is there anything else that can be found out about this cryptogram? If so, please let me know.

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Further reading: An encrypted letter from World War 2

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13501820

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/763282653806483/

Kommentare (10)