About a century ago, a young man from Austria wrote an encrypted postcard with a sad motive to his lover. Can a reader decipher this cryptogram?

When I write about an encrypted postcard, I often need to take a geography lesson. Cards I have covered on this blog were sent from places such as Mannswörth, Newport, and Colchester, just to name a few. The recipients lived, among other things, in Orimattila, Aschersleben and Landreville.

When I first looked at the postcard I’m going to introduce today (I found it on the website DYUZAOJ), the geographical part was easy. The card was sent to a woman in St. Pölten, today the capital of Lower Austria (Niederösterreich), one of the nine states of Austria.

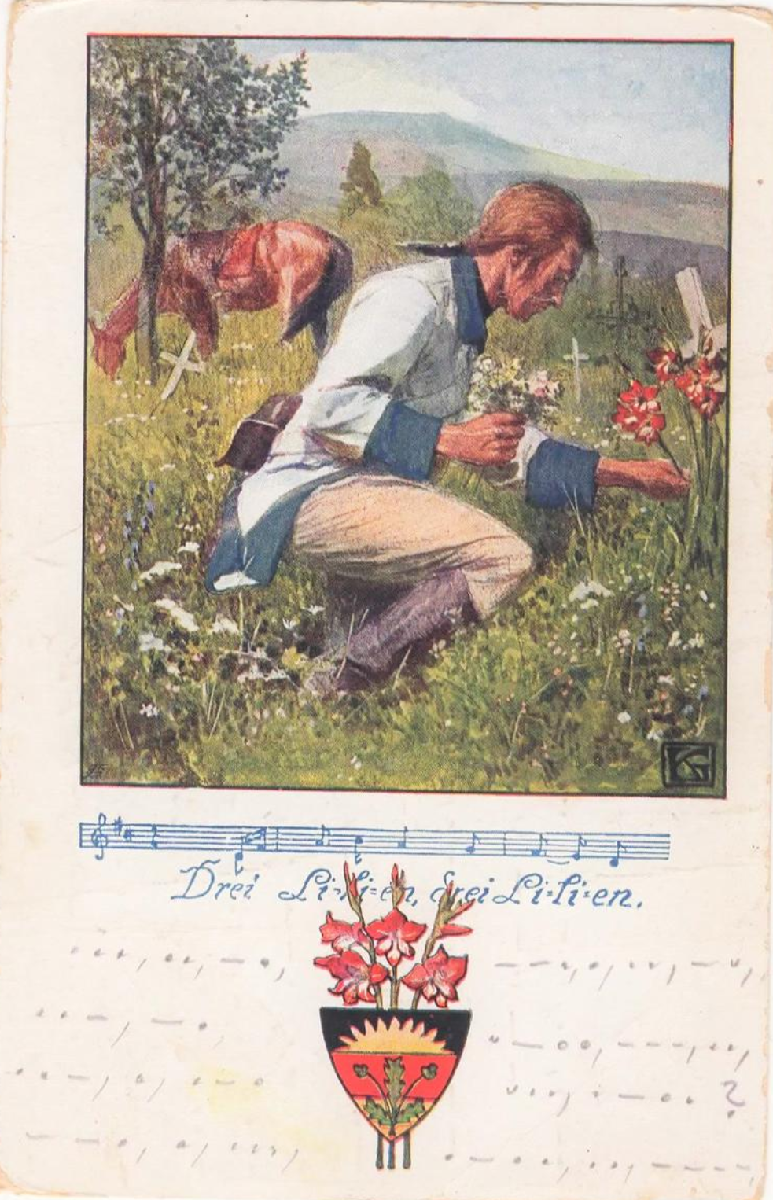

However, this time I faced a musical problem. The picture side of the postcard shows musical notes along with the words “Drei Lilien, drei Lilien”, which translates to “Three lilies, three lilies”. I had never heard of a musical piece of this name, but the problem was easily solved with YouTube. As I found out, there is a German soldier song titled “Drei Lilien”, which is often played as a march. The following version is sung by the German musician Ronny:

There are different versions of this song. The composer appears to be unknown.

Let’s now look at the postcard:

The motive shows a soldier picking lilies, as well as a few crosses (graves?) in the background. Apparently, this scene refers to the song lyrics.

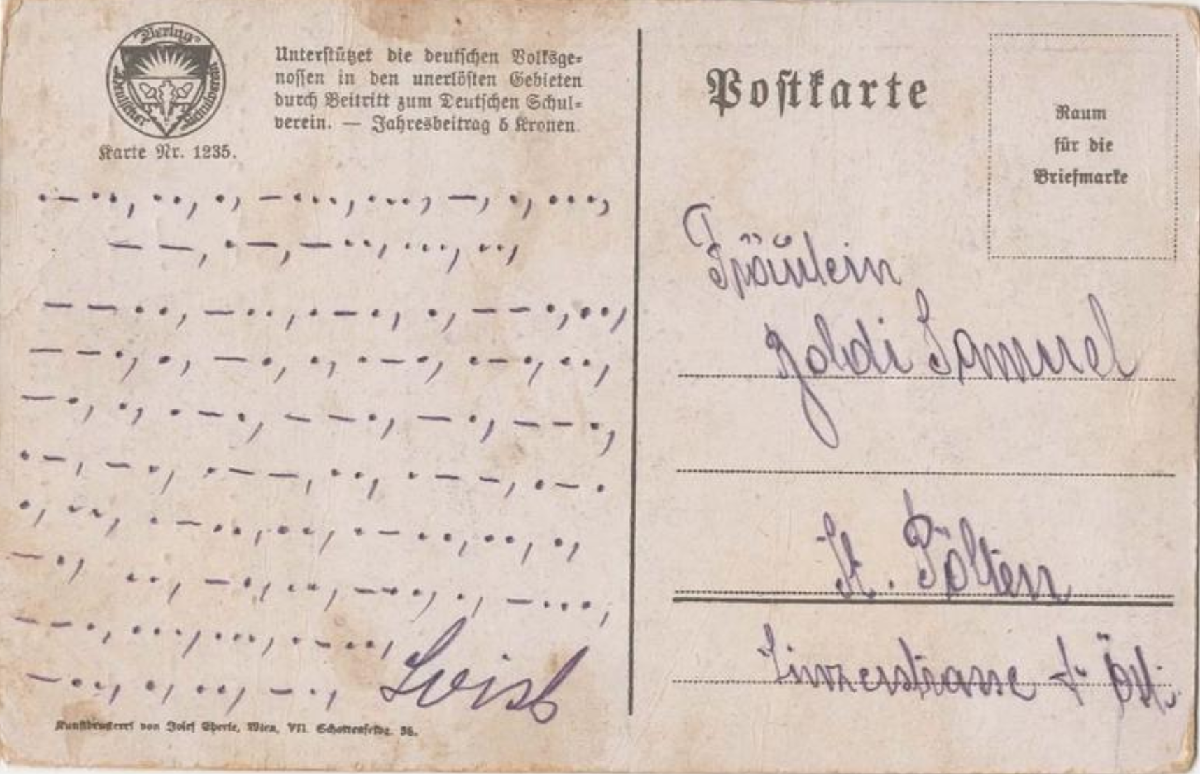

On the address side, …

… we see that the recipient was an unmarried woman (“Fräulein”) named Goldi Samuel living in the Linzerstrasse (?) in St. Pölten, Austria. Apparently, this encrypted postcard was sent, like so many others, by a young man to his lover.

The message is signed, but I can’t read the signature. Can a reader help?

To my regret, the card isn’t dated. It certainly stems from the early 20th century, perhaps from the time around World War I. I hope my readers will be able to find out more.

Finally, can a reader decipher the Morse code the card was written in? It’s probably not very difficult and it might help to learn more about the background of this card. Good luck!

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Further reading: Can you decipher this postcard from 1916?

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13501820

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/763282653806483/

Kommentare (32)