A coded dispatch from 1812 and its exciting story

Blog reader Karsten Hansky sent me an interesting encrypted document from France. He provided the decryption and detailed information about the historical background.

Karsten Hansky has already provided me with many an interesting encrypted document from his collection for Cipherbrain – including a book and several postcards, to name just a few examples. A few days ago another document was added: It is about a coded dispatch from France.

A dispatch, I learned on this occasion, is an urgent message and therefore different from a letter. In this case, the dispatch was transported by mounted messenger or by sea. This was not the normal way for ordinary mail.

The coded dispatch

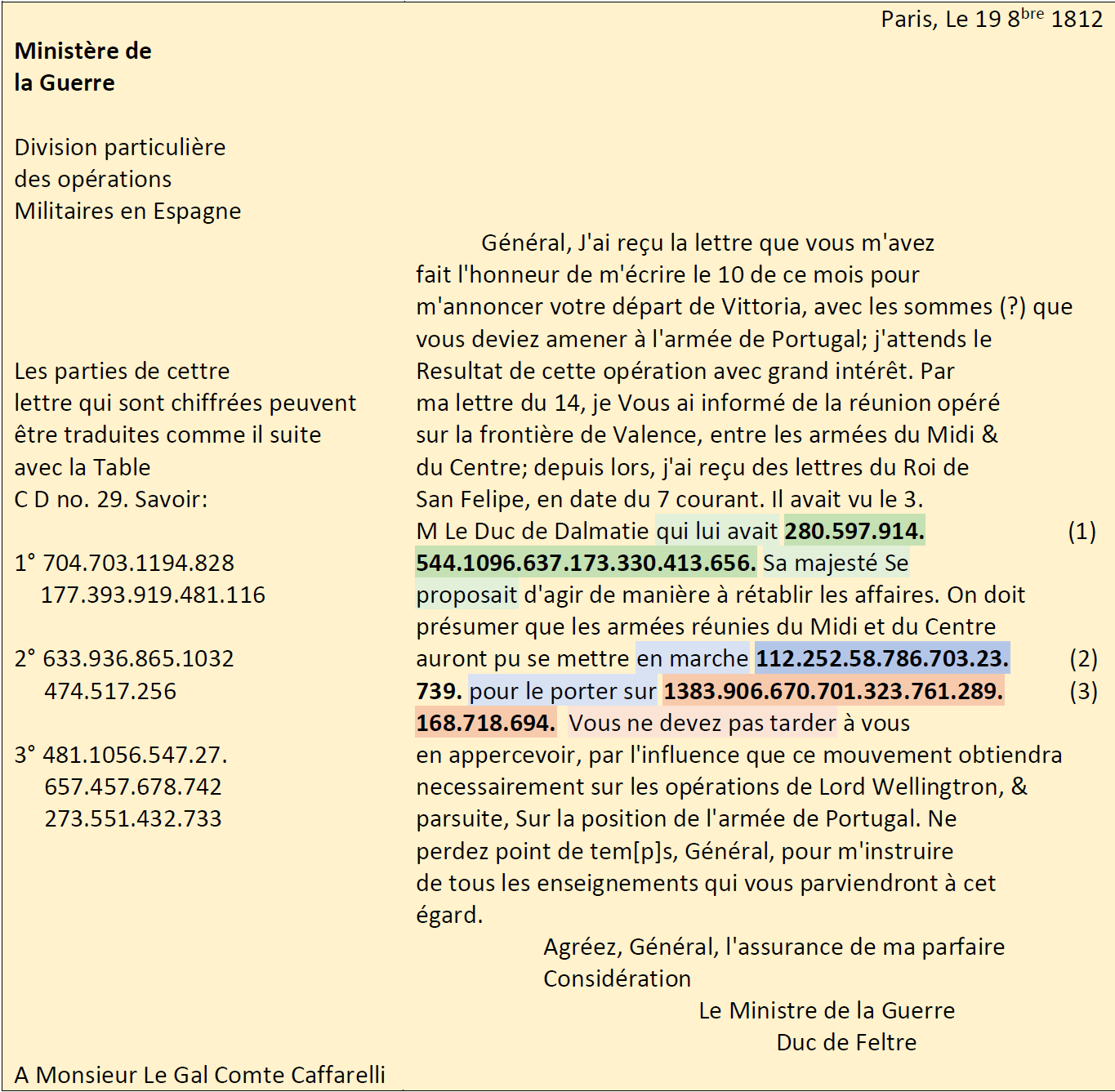

The sender of the dispatch was the French Minister of War Henri Clarke (1765-1818). He sent the letter from Paris on October 19, 1812 to General Marie-François Auguste de Caffarelli du Falga (1766-1849), commander of the Northern Army in Spain.

Karsten has thankfully left me a detailed and impressively well-researched account of the dispatch and its background. This very readable work is available here in German and English. Besides Karsten, the French crypto history expert Jean-François Bouchaudy has contributed. This blog article is based on this previously unpublished work.

Karsten acquired the Clarke Deposition from an American dealer via Internet auction in the spring of 2021. There is no further information about its provenance, except that the dealer bought the document at an estate auction. Here is a scan:

Karsten has created the following transcription:

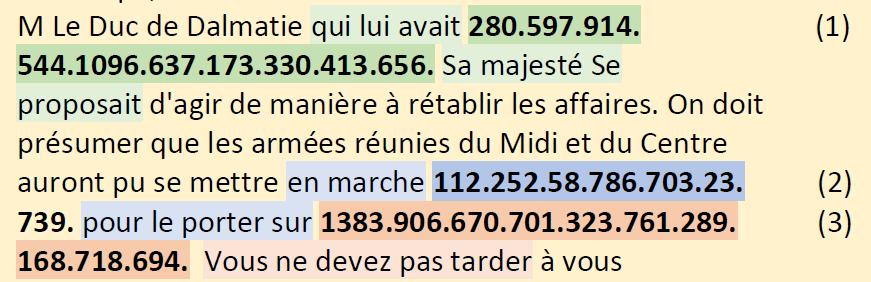

The dispatch is written in French. Three text passages (marked in color) are encoded with numbers, the rest is noted in plain text. Apparently, a nomenclator was used for encryption.

The left column contains further encrypted text passages. This is, as Karsten has determined, an encryption of the same plaintext by means of another code table. I will not go into this in detail.

The background

Karsten has researched the background of the Depeche very thoroughly, which I summarize below. In 1812 France had occupied large parts of Spain. The French troops divided into several armies:

- Army of the North under the command of General Caffarelli.

- Army of Portugal under the command of General Souham

- Central Army under the command of King Joseph Bonaparte (brother of Napoleon), who was assisted by Marshal Jourdan as Chief of Staff

- Southern Army under the command of Marshal Soult

- Army of Aragon and Valencia under the command of Marshal Suchet

- Army of Catalonia under the command of General Decaen

Opposing the French armies was an alliance of the British Expeditionary Army and Portuguese troops. This alliance was commanded by Lord Wellington.

Between September 19 and October 21, 1812, Wellington’s army laid siege to the city of Burgos. This was preceded by an important victory of the allied forces in the Battle of Salamanca on July 22, 1812, in which the French Army of Portugal under the command of Marshal Marmont suffered heavy losses. Marshal Marmont was seriously wounded during the battle, and General Souham took command of the Army of Portugal.

In the weeks that followed, Wellington’s troops marched on the capital, Madrid. In September 1812, Lord Wellington divided his army. He marched part of his force north from Madrid toward Burgos, while General Rowland Hill took up position with the rest of the troops south of Madrid on the Tagus River to establish a defensive line against the southern French armies. Few troops were left behind in Madrid.

Lord Wellington undertook the siege of Burgos because, in his estimation, the Army of Portugal had not yet replenished the losses from the Battle of Salamanca and was therefore not yet ready for a new offensive. The Northern Army under General Caffarelli was kept busy by guerrilla fighters in various places, so Wellington assumed that no troops could be detached from there to support the Army of Portugal. Wellington likewise expected no advance of the southern army under Marshal Soult toward Madrid, since this would require all of Andalusia to be cleared of French troops.

However, all these assumptions proved to be wrong. Marshal Suchet’s troops were considered strong enough by the French to hold Valencia without further support. The southern army of Marshal Suchet united with the central army of King Joseph and started to move north. Andalusia was actually cleared of French troops in the process. At the same time, General Caffarelli with about 10,000 men marched from Vitoria through Briviesca towards Burgos to support the army of Portugal and challenge Wellington to a battle.

The long duration of the siege of Burgos and the false assumptions about the actions of the French troops put Lord Wellington on the spot. He was outnumbered with his troops in the north by the Army of Portugal and its reinforcements by the Northern Army. The same was true in the south for General Hill’s troops on the Tagus, who were outnumbered by the combined central and southern armies.

For the Allied troops, the acute threat of being attacked by a pincer movement simultaneously in the north and south arose. Lord Wellington broke the siege of Burgos just in time before the arrival of the French armies. He ordered General Hill and his troops north toward Salamanca to join him. The capital, Madrid, was abandoned and, as it progressed, the Allied troops retreated to Ciudad Rodrigo on the Spanish-Portuguese border.

The plain language

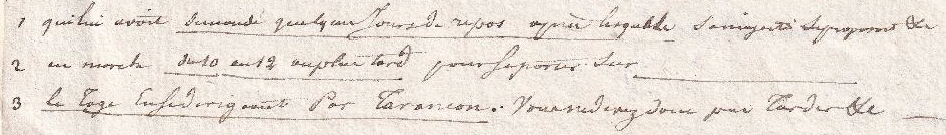

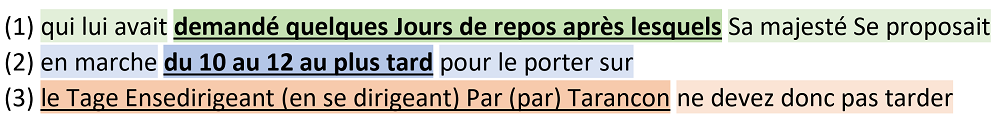

Normally at this point I would ask how to decrypt this cryptogram. However, that is not necessary in this case, because a note with the plaintext of the coded passages is stapled to the dispatch:

Here is Karsten’s transcription:

If we compare this text with the transcription of the coded passage in the dispatch, it also becomes clear what the individual numbers stand for (there is a detailed comparison below):

Translated into German, the plain text reads as follows:

General,

ich habe den Brief, den Sie mir am 10. d. M. geschrieben haben, um mir Ihre Abreise aus Vittoria, mit den Beiträgen [Truppen?, Verstärkung?], die Sie der Armee von Portugal bringen müssen, mitzuteilen, erhalten; ich erwarte das Ergebnis dieser Operation mit großem Interesse. Mit meinem Brief vom 14. habe ich Sie über die an der Grenze von Valencia zwischen den Armeen des Südens und des Zentrums durchgeführte Vereinigung informiert; seitdem habe ich die Briefe des Königs von San Felipe mit Datum des 7. d. M. erhalten. Er hatte am 3. den Herzog von Dalmatien, um einige Ru-hetage erbeten. Seine Majestät schlug vor, so zu handeln, um die Unternehmung wiederherzustellen. Es ist anzunehmen, dass die vereinigten Armeen des Südens und des Zentrums sich vom 10. bis spätes-tens zum 12. in Marsch setzen konnten, um den Tajo in Richtung Tarancón zu kommen. Sie dürfen das also bald selbst durch den Einfluss, den diese Bewegung notwendigerweise auf die Handlungen von Lord Wellington und, in der Folge, auf den Standort der Armee von Portugal haben wird, feststellen. Verlieren Sie keine Zeit, General, mich über alle Kenntnisse, die Ihnen in dieser Hinsicht zukommen, zu informieren.

Mit freundlichen Grüßen [an eine rangniedere Person]

Der Kriegsminister Herzog von Feltre

An Herrn General Graf Caffarelli

The nomenclator

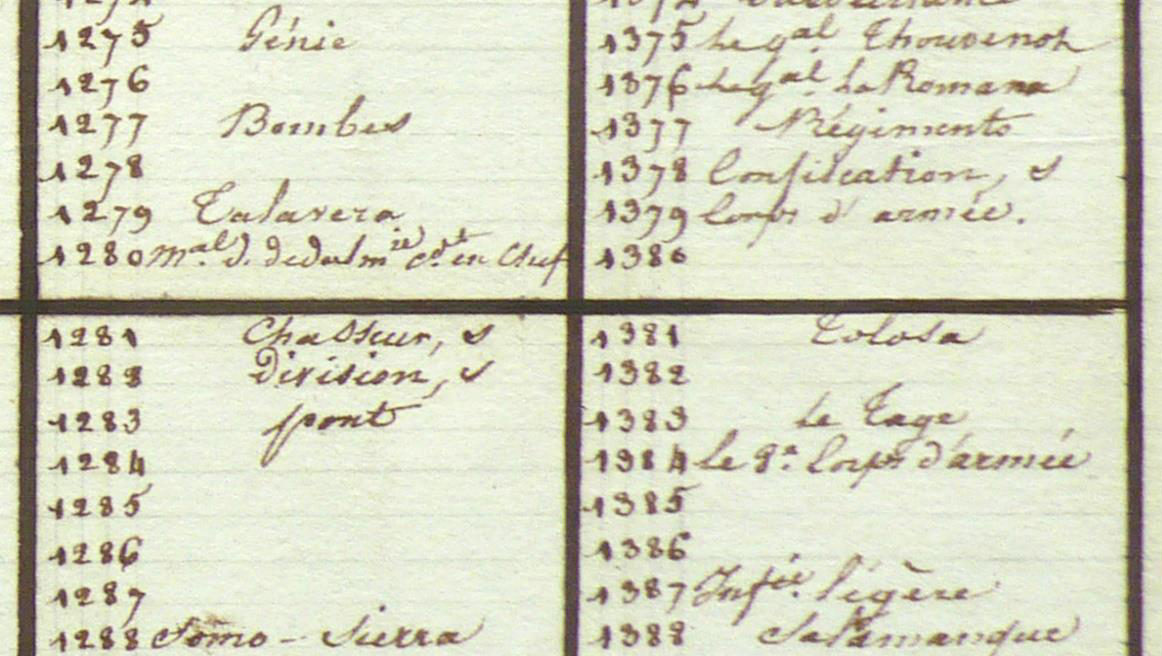

Even without the attached note, one could have deciphered the Clarke dispatch. The aforementioned French crypto-history expert Jean-François Bouchaudy found the corresponding nomenclator (it is the so-called “Great Cipher”) in the archives of the SHD (Service Historique de la Défense) in Vincenne (SHD box 1M-2352).

The following excerpt from the nomenclator shows code group 1383 (“le Tage”):

Based on this table, the coded text passages can be read as follows:

(1) 280 – 597 – 914 – 544 – 1096– 637– 173– 330 – 413 - 656 demandé – quelques – jours – de – re – po – s – après – les – quels. (2) 112– 252 – 58 – 786 – 703 – 23 – 739 du – dix – aux – douze – aux – plus – tard (3) 1383 – 906 - 670 – 701 – 323 – 761 – 289 – 168 – 718 – 694 Le Tage – en – se - direct - ant – par – ta – ra – n – con

The word “direct-ant” must actually be “dirigeant”. It is possible that the secretary responsible for coding did not find the appropriate syllables in the nomenclator.

George Scovell

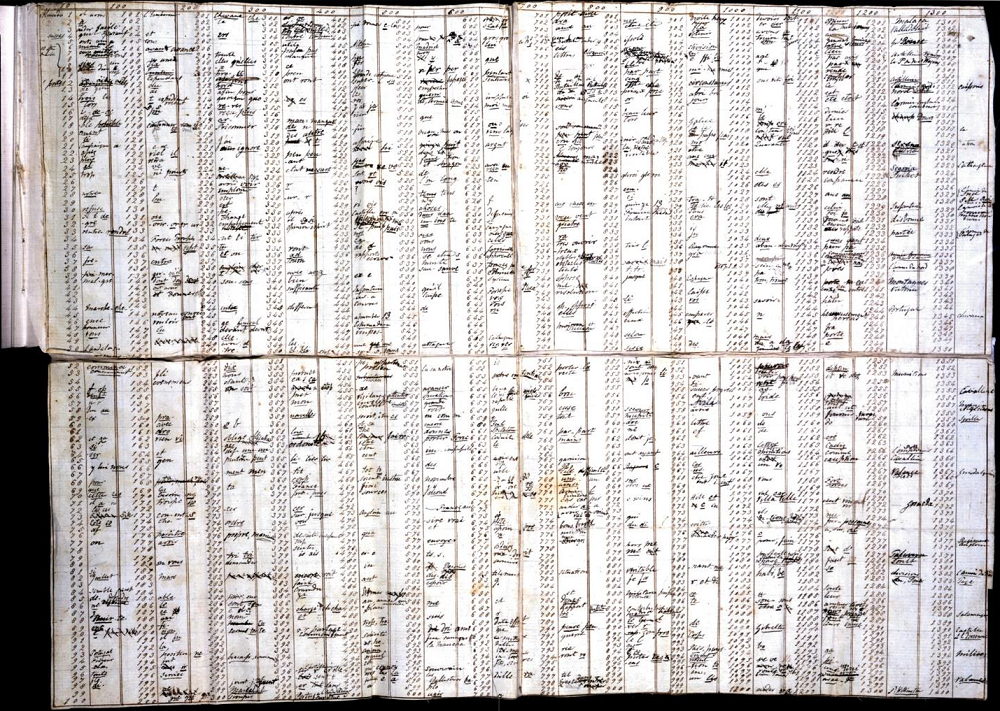

As we know today, Lord Wellington was able to read the “Great Cipher” to a large extent. George Scovell, a British officer and codebreaker, was responsible for this. In painstaking detail, he succeeded in reconstructing large parts of the code table from a large number of intercepted dispatches – a groundbreaking work for the time. The following figure shows his reconstruction of the nomenclator:

E

n open question

To conclude this long article, I would like to thank Karsten Hansky and Jean-François Bouchaudy very much. It is really impressive what they have found out about this dispatch. I am very happy that Karsten gave me the opportunity to publish his detailed research results on my blog.

However, there was one question Karsten could not answer. It is about the name “Roi de San Felipe” (“King of San Felipe”). This refers to King Joseph Bonaparte. Despite intensive research, Karsten has not been able to establish a connection between King Joseph and San Felipe. Jean-François Bouchaudy has no idea either. Does a reader know more?

If you want to add a comment, you need to add it to the German version here.

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Further reading: Das verschlüsselte Telegramm eines Astronomen

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13501820

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/763282653806483/

Letzte Kommentare