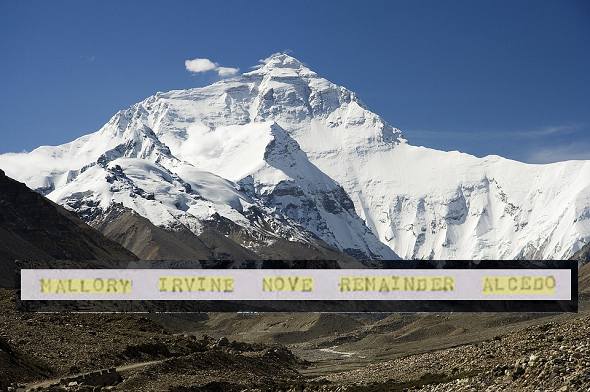

In 1924, British mountaineers George Mallory and Andrew Irvine died trying to be the first to climb Mount Everest. An encrypted telegram reported the drama to their homeland. A blog reader identified the codebook that was used, but there is still one word, the meaning of which is unknown.

Who was the first to climb Mount Everest? Experts largely agree that it were Edmund Hillary from New Zealand together with the Sherpa Tenzing Norgay in 1953.

Hillary or Mallory?

Especially in Great Britain, however, some see British mountaineers George Mallory and Andrew Irvine as the first, who reached the world’s highest mountain. The two died during their climb attempt in 1924. Theoretically, it is possible that Mallory and Irvine had already reached the summit when they deceased. However, not only Mount Everest veterans Reinhold Messner and Hans Kammerlander consider it impossible that the two British mountaineers actually climbed up to 8848 meters. They route they chose is known as difficult today; the equipment of the time was weak compared to later years; and the weather conditions were far from optimal.

I have always followed the discussions about George Mallory (he was the much better mountaineer of the two, which is why the ascent attempt is usually linked to his name) with great interest. One of the reasons for this is that Mallory’s last name caught my eye. In cryptography, Mallory is the fictitious villain who eavesdrops the communication between Alice and Bob, always trying to break their encryptions. Mallory plays an important role in my book Kryptografie – Verfahren, Protokolle, Infrastrukturen. His name is derived from “mal” and has nothing to do with the famous mountaineer.

Apart from his last name, there is another reason why George Mallory is sometimes mentioned in crypto history discussions. When once asked why he wanted to climb Mount Everest, he replied: “Because it is there”. I sometimes give a similar answer when somebody asks me why so many are interested in deciphering the Voynich manuscript or other historical cryptograms. We simply want to solve these mysteries because they are there.

The Mallory telegram

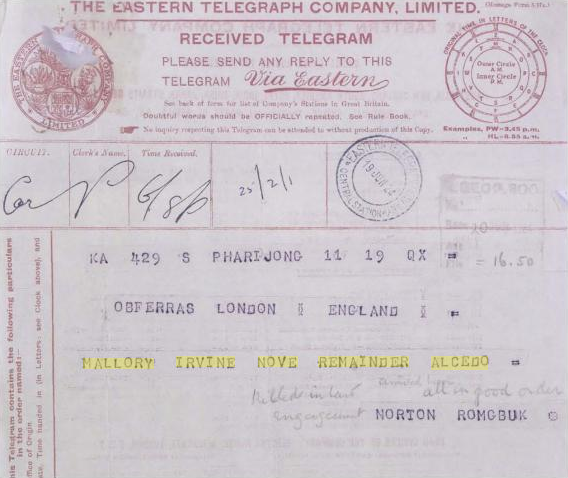

Three years ago, blog reader Alexander thankfully pointed out to me that there is another, much more direct relationship between George Mallory and cryptography. After the ascent attempt that resulted in Mallory’s death, a member of the expedition sent a message from the base camp to Great Britain. After a courier hat brought this message to the town of Pagri, it was sent to London by telegram on 19 June 1924.

The message read: MALLORY IRVINE NOVE REMAINDER ALCEDO.

As can be seen, the telegram contains two codewords: NOVE and ALCEDO. At that time it was quite common to encrypt telegrams by replacing important words with codewords. There were codebooks containing tens of thousands of entries for this purpose.

When I wrote a blog post about this telegram in 2015 (in German), the codebook used by the Mount Everest expedition was still unknown. We could decrypt the message anyway, because the recipient of the telegram wrote the meaning of the two codewords on the telegram sheet. NOVE means “killed in last engagement”, while ALCEDO stands for “arrived all in good order”. This confirms that codebooks were not only used for encryption, but also for shortening telegrams (the shorter a telegram, the cheaper it was). In many cases this shortening was even the actual reason to use a codebook.

Decoded the telegram reads: MALLORY IRVINE KILLED IN LAST ENGAGEMENT, REMAINDER ARRIVED ALL IN GOOD ORDER.

After I had published my blog post, reader Robert posted the title of the codebook I had been looking for: the Universal Telegraphic Phrase-Book. The edition of this codebook Robert linked is from 1889. I assume that the Mount Everest expedition, which took place in 1924, used a later issue. In any case, the codewords NOVE and ALCEDO are contained in this code with the same meaning as noted on the telegram sheet.

There is still one question to be answered: the meaning of the word OBFERRAS, which stands above the actual message, is not known to me. Does a reader know the answer?

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Further reading: The Top 50 unsolved encrypted messages: 14. The Codex Seraphinianus

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13501820

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/763282653806483/

Kommentare (13)