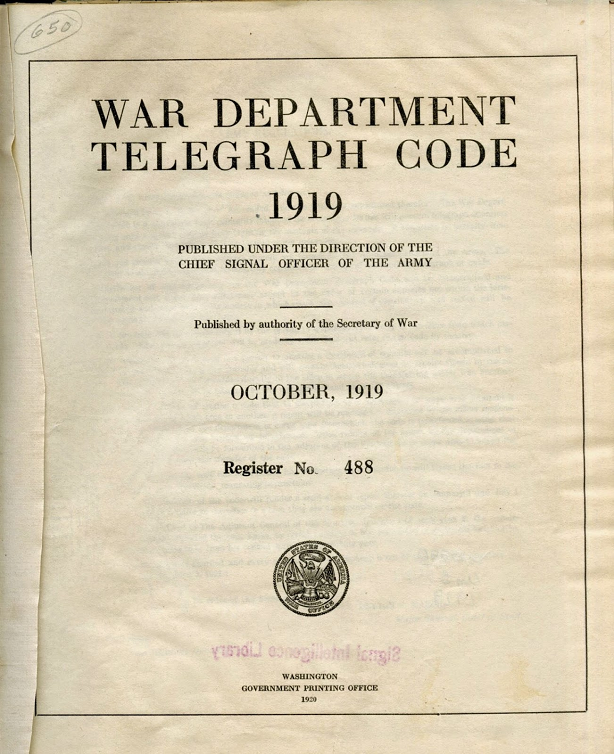

Der TELWA-Code, so schreibt Triantafyllopoulos, hieß eigentlich War Department Telegraph Code und wurde auch SIGARM genannt (die Buchstaben SIG kommen in ziemlich vielen militärischen Verschlüsselungsverfahren der USA vor, beispielsweise in SIGFOY, SIGSALY, SIGABA und SIGCUM). Die von Weber geknackte Version stammte aus dem Jahr 1942. Es gibt außerdem eine ältere Ausgabe von 1919 (SIGRIM). In Triantafyllopoulos’ Artikel ist die Titelseite der Version von 1919 abgebildet:

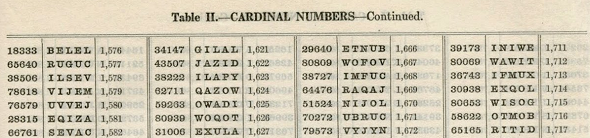

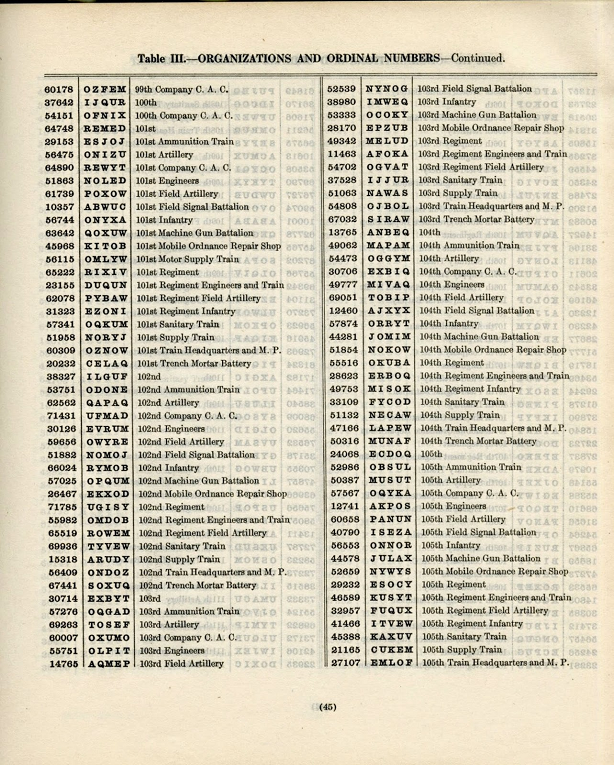

Und hier ist eine Seite daraus:

Beide Code-Versionen wurden für administrative Informationen ohne besondere Geheimhaltungsanforderungen verwendet. Vermutlich war den Amerikanern klar, dass der TELWA-Code zu knacken war.

Auch bei Wikipedia gibt es inzwischen einen Artikel über den TELWA-Code. Dort heißt es: “Er wurde über einen langen Zeitraum benutzt und daher in verschiedenen, abgeänderten Auflagen herausgegeben, so z.B. 1919 und 1942. Er diente zur Verschlüsselung von Verwaltungs- und Personalsachen ohne strategische Bedeutung. Der Code umfasste mehrere tausend Gruppen zu je fünf Buchstaben, so angeordnet, daß die Gruppen aussprechbar waren.”

Damit ist für mich eine Frage beantwortet, die ich zehn Jahre lang mit mir herumgetragen habe. Ich werde diese Sache zum Anlass nehmen, endlich einmal den Blog von Christos Triantafyllopoulos systematisch durchzuarbeiten. Vielleicht erlebe ich ja noch ein paar Überraschungen.

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Zum Weiterlesen: Ungelöst: Ein verschlüsselter Brief aus dem Jahr 1783

Kommentare (6)