The challenges of Giouan Battista Bellaso were one of the top unsolved crypto mysteries. Norbert Biermann has now published the last two parts of the solution.

When I wrote my article series about the top 25 unsolved crypto mysteries in 2013 (in German), a series of cryptograms from Italy ranked number 11: Giouan Battista Bellaso’s challenges from 1555 and 1564. These ten challenges are the oldest crypto excercises known in the codebreaking community.

Bellaso’s challenges

Bellaso published three of the challenges in his book Noui et singolari modi di cifrare (1555), the seven others in Il uero modo di scriuere in cifra (1564).

On his webpage, Nick Pelling presents transcriptions of all ten cryptograms. For instance, here’s the first one from the first book:

Frzf polh hebx ghqf xtou ulfh gihm qbgn* yoep rpmi porn zngy

gzop zctm qdfl hian bxbu dqmt dnul ayxm cars gsgc xrch omdo

cgmh hxpc bom*f rntr oyqz zhim hsph mphr xrfh omd’a updq bedp

rhxe flfg dqlb dcdq cxrf glmb pctq pnpy fdeo zcxt braz bude

qpyh gnfp beinu ndqa ngxn bloc auyu btos iblx fbyid fxyh mctf

tmoz fhlb aich oqep luzi ucxe nctb ghpz lbxu flzs myxt nbon*

loge nxhq xyef nzgh ryrd myrf qfao dqse tryr cqtx ddbx nscu

hpnq qscq hqry gnsp huam pfpn fdcg tbsn lman smlb zcmb easa

qemb udoa cxph rsqgf yrnf fgep itia amsy acih sxth tsfd cxph

lyni rupt ygdr enqn nfhi enbe* engc monb qogt rszy clcx aldu

ayix ttis phms asbl cpix gnsr tyeo qxrf yedx mtgix rhcm xuhf

sghr opbg slbo cecu flhb npfc e*rep gdqv bzpr haum prpc doxd

qylp hqfq dimtu ibgs xelc hgsh zumh qbxa xcqt pilb ocud slgl

hgdh uhpd hbxe fltq yayg bdcle gmtn umni utpl tufq bdzo sfzb

yezd xnqc opcy pyhq efso zsbm ornd hudc nulr ryrn pxlnu tgdaz

In the 1990s, Italian crypto historian Augusto Buonafalce made Bellaso’s challenges known to a wider audience. In January 2006, he presented them in a Cryptologia article. In 2009, Nick Pelling published the challenges on his blog. Among Pelling’s readers was Tony Gaffney (now also a reader of Klausis Krypto Kolumne), who is known as a great codebreaker.

This is what happened next:

- March 31, 2009: Tony Gaffney reports the solution to challenge #6 from the second book.

- March 19, 2009: Tony posts two more solutions: #1 and #2 from the second book.

- April 27, 2009: Tony solves #7 from the second book.

- May 5, 2009: Tony publishes solutions #3 and #4 from the second book.

Six of ten challenges were solved now. The story continued in 2016:

- March 30, 2016: Norbert Biermann publishes the solutions of the first challenge of the first book and the fifth challenge of the second book as comments on my blog.

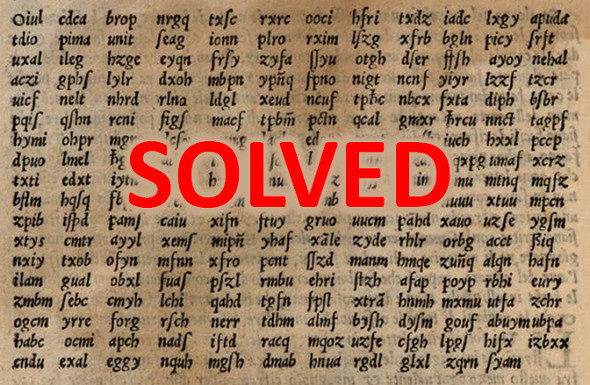

Now, two challenges (#2 and #3 from the first book) remained unsolved. Here is a scan of these two ciphertexts:

The last two mysteries solved

Last year, Norbert told me that he had solved challenges #2 and #3 from Bellaso’s first book, too. However, I could not announce this success, as Norbert planned to publish his work in Cryptologia. On February 12, 2018, Norbert’s solution description was made available on the Cryptologia website.

This means that, after almost 500 years and over 20 years after their rediscovery by Augusto Buonafalce, Bellaso’s challenge ciphers are now completely solved. Congratulations to Norbert and Tony! I am very proud that my blog played a role in the solution of this mystery.

How Norbert solved the challenges

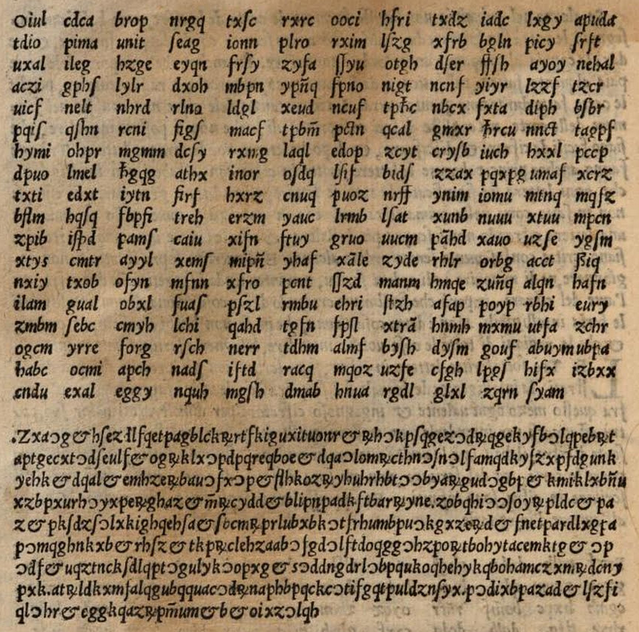

Giouan Battista Bellaso is known as one of the inventors of polyalphabetic encryption. In his publications, he suggested the use of substitution tables that looked like this one:

Using this table to encrypt the message CRIPTO with the keyword TEST works as follows:

- The C is encrypted with the ST table (because ST contains T, which is the first letter of the keyword). C encrypts to R.

- The R is encrypted with the EF table (because EF contains E, which is the second letter of the keyword). R encrypts to F.

- The I is encrypted with the ST table (because ST contains S, which is the third letter of the keyword). I enccrypts to Z.

- The P is encrypted with the ST table (because ST contains T, which is the fourth letter of the keyword). P encrypts to A.

- The T is encrypted with the ST table (because ST contains T, which is the first letter of the keyword). T encrypts to E.

- …

This means that CRIPTO encrypts to RBZAEC. All in all, this method is very similar to the Vigenère Cipher, which was introduced a few decades later.

It comes as no surprise that Bellaso used this encryption technique for the first two challenges in his first book. The third ciphertext is encrypted in a similar way.

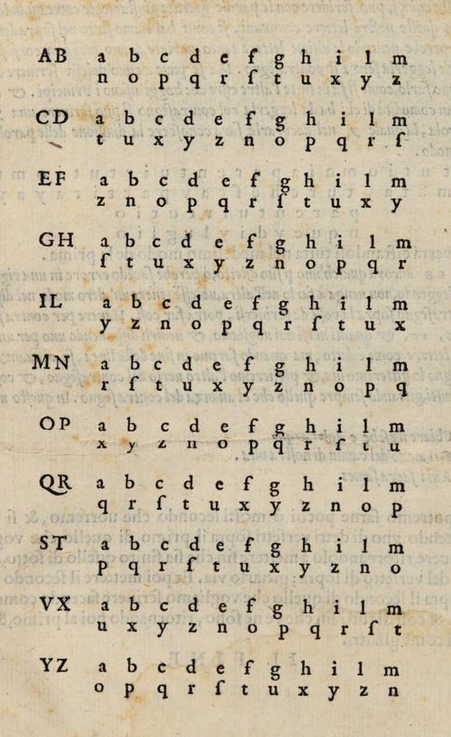

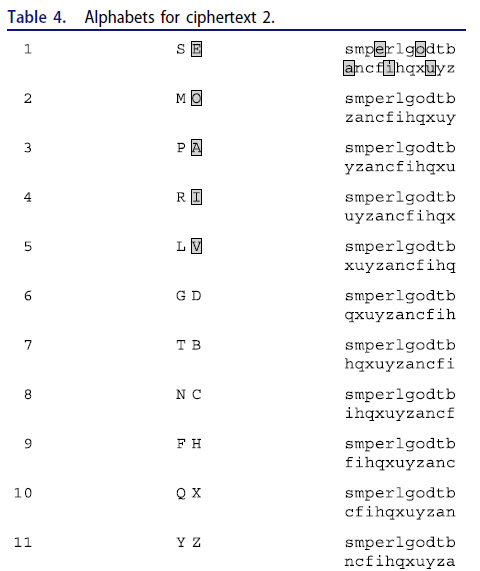

Norbert Biermann solved the three ciphertexts from Bellaso’s first book with a technique that is certainly familiar to many readers of this blog: hill climbing. To be more precise, he used simulated annealing, which is a hill climbing variant. For instance, here’s the table Norbert’s hill climbing program found for the second challenge of the first book:

The keyword of the first challenge is actually a key poem (Eclogue 3 by Virgil, verse 28–31). For his second challenge, Bellaso used an excerpt from Psalm 50. The third ciphertext is not based on a keyword.

The cleartexts

Here’s the cleartext of Bellaso’s first ciphertext (book #1):

Al magnifico et illustre Signor Pompeo Avogaro parente et compare suo osservandissimo.

Tra tutte le inventioni del mondo ho sempre giudicato la inventione degli

caratteri essere la più degna anzi singolare; mediante la quale si parla insieme

anchor che di luntano come se di appresso. Si fusse cosa in vero sopra mondo

non meno utile che ingegnosa? Il primo honore appo questa inventione darei

à la cifra con il cui mezzo non solamente di luntano l’uno l’altro si parla, ma

che di più ciò si fa a malgrado d’ogni uno senza essere intesi da alcuno fuori

che dove si vuole; il che quanto sia utile anzi necessario al mondo per le varie

occorrenze et sottilità degli huomini. Ne ponno fare gli principi testimonio

chiarissimo perciò che la maggior parte delle più importanti cose loro si

spediscono con le cifre.

Here’s cleartext #2:

Al Signor Vincenzo Maggio, philosofo eccellentissimo, suo cugino osservandissimo.

Finito che ho l‘ufficio della consolaria de’ quartieri per levarmi alquanto

della mente le grandi confusioni et contrarietà de’ dottori legisti moderni.

Gli quali hanno di modo con gli loro scritti involuppate le leggi nelle ciance

loro, che non le leggi, ma le passioni, cavillationi, et vani sottilità dilettosi, et

avaritia per consultori fanno hoggidì le sentenze; et se il foco non gli provede,

stemo male et per l‘avenire peggio.

Ho pigliato in mano le meccaniche del vostro de ingegno divino Aristotele et

insieme considerate alcune sue questioni. Ho composto per capriccio una

arghena de rote diciotto. Tredici de’ quali son talmente proportionate insieme,

che finiscono il loro circuito tutte in un punto. Otto pesi ne levano cento; laonde

credo, che li antichi Romani usassino simili instrumenti per tirare et levare quelle

pietre, le quali a vederle et pensare a che modo fussino mosse, ci fanno stupire.

Here’s the third cleartext:

Hoc sermone eruditionem omnibus commendabat Diogenes, quod diceret

eam iuvenibus adferre sobrietatem, senibus solatium, pauperibus divitias,

divitibus ornamentum: propterea quod ætatem, suapte sponte lubricam

coerceat ab intemperantia, senectutis incommoda honesto solatio mitiget,

pauperibus sit pro viatico, non enim egere debent eruditi.

Aristoteles dicebat eruditionem in prosperis esse ornamentum, in

adversis refugium. Parentes qui liberos suos recte instituissent, aiebat multo

honorabiliores esse iis qui tantum genuissent, quod ab his contigisset vivere,

ab illis etiam bene vivere.

Again, congratulations to Norbert Biermann on this great codebreaking work!

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Further reading: The Top 50 unsolved encrypted messages: 27. Ferdinand III’s encrypted letters

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13501820

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/763282653806483/

Kommentare (16)