Already 30 years ago, US historian Albert C. Leighton collected historical cryptograms and tried to coordinate the study of these. He even thought of an equivalent of today’s crypto history conference, HistoCrypt. To my regret, nobody seems to know what happend to his collection after his death.

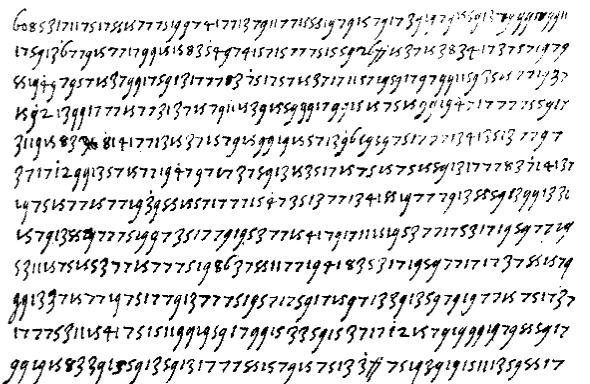

When twelve years ago I wrote the first edition of my steganography history book Versteckte Botschaften, I came across an interesting article published by a certain Albert C. Leighton in Cryptologia. This article is about a letter from the 16th century that looks like this:

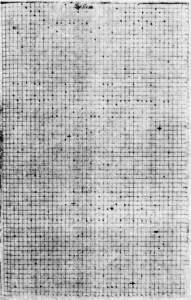

As Leighton found out, each dot on this squared paper stands for a letter. This position of a dot determines which letter it representes. For somebody not familiar with this encoding technique (it is referred to as “dot cipher”), this simple drawing doesn’t look like a letter at all – this is why a dot cipher is a steganographic technique.

Leighton could decipher the dot cipher message and found out that it was written by a high-ranked member of the Catholic Church from Cologne to a nobleman in Munich. The sender of the message complains that the pope has provided him only ten thousand Crowns, which is, in his opinion, much to little in his fight against the Protestants.

When I browsed through other old issues of Cryptologia and did some online research, I realized that Albert C. Leighton had authored a few more papers about breaking of historical cryptograms. The following list is probably not complete:

- 1969: A Papal Cipher and the Polish Election of 1573 (Jahrbücher der Geschichte Osteuropas)

- 1977: Some examples of historical cryptanalysis (Historia Mathematica)

- 1977: The earliest use of a dot cipher (this is the paper mentioned above) (Cryptologia)

- 1993: The statesman who could not read his own mail (Cryptologia)

- 1984: The History of Book Ciphers (Proceedings of CRYPTO)

- 1983: The Search for the Key Book to Nicholas Trist’s Book Ciphers (Cryptologia)

- 1996: A mystery solved (Cryptologia)

These publications provided interesting input for my books and articles. Especially in my book Codeknacker gegen Codemacher Leighton is mentioned several times.

Albert C. Leighton also published a book titled Transport and Communication in Early Medieval Europe AD 500-1100. The content is not cryptologic in nature.

Who was Albert C. Leighton?

Of course, I wanted to know who Albert C. Leighton was. Apparently, he was born in 1919 in Chester, New Hampshire. He worked as a military codebreaker in the team of William Friedman from 1938 to 1957. Afterwards, he attended the University of California at Berkley. In 1967 he started an academical career as a professor of Ancient and Medieval History at the University of New York in Oswego. Later he moved to San Antonio, Texas.

As can be seen in the list above, Leighton’s last paper known to me was published in 1996 (when he was 77). I assume that he has died in the meantime. I don’t have any information about his late years.

In his publications, Leighton mentioned at least a dozen historical cryptograms. He discussed historical codebreaking with other historians and tried to coordinate research efforts. He even thought of a conference series similar to HistoCrypt, which came to life only decades later. I am sure that Leighton had a large collection of crypto literature, historical cryptograms, personal notes and similar stuff – like everybody has, who does research in this field.

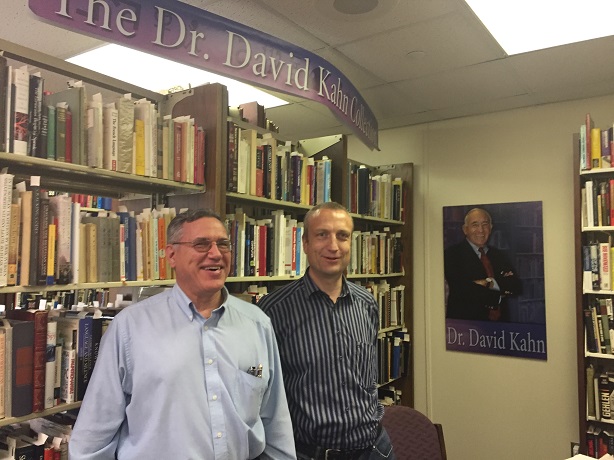

Of course, it would be very interesting to know what happened to Leighton’s collection after his death. Material of this kind is often donated to archives or libraries. For instance, William Friedman’s files are now available at the Marshall Library in Lexington, Virginia. David Kahn, who is still alive, has donated a large part of his collection to the library of the National Cryptologic Museum, which has resulted in the “Dr. David Kahn Collection” (the following picture shows me together with Tony Patti with a part of it).

Other late crypto experts, like Jack Levine, Louis Kruh, David Hamer, and David Shulman have left behind impressive collections, too. They are goldmines for crypto history enthusiasts like me.

However, no source I know mentions an Albert C. Leighton collection.

At HistoCrypt in Uppsala, Craig Bauer, the editor-in-chief of Cryptologia and author of the book Unsolved!, told me that he had tried to find out the whereabouts of Leighton’s files, too – but to no avail.

Can my readers help?

Perhaps, a reader can help in this situation. Does anybody know where and when Albert C. Leighton died? Did he have children I can contact? Did he or his descendants donate his research material (which is probably for the most part not crypto-related) to an archive or library? And do you know other crypto-related publications of Albert C. Leighton? If so, please let me know.

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Further reading: History’s greatest codebreaker versus history’s greatest imposter

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13501820

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/763282653806483/

Kommentare (11)