Das Dorabella-Kryptogramm, das von dem Komponisten Edward Elgar stammen soll, ist eine der bekanntesten ungelösten Verschlüsselungen. Einige Indizien sprechen dafür, dass es sich um eine Fälschung handelt.

English version (translated with DeepL)

Einer meiner letzten Blog-Artikel stellte fünf mehr oder weniger bekannte verschlüsselte Botschaften vor, bei denen es sich wahrscheinlich um Fälschungen handelt. Demnächst wird es eine Fortsetzung mit weiteren Beispielen geben.

Das Dorabella-Kryptogramm, eines der bekanntesten ungelösten Krypto-Rätsel überhaupt, wird dagegen in der (ziemlich umfangreichen) Literatur kaum als mögliche Fälschung diskutiert. Dies gilt zugegebenermaßen auch für die von mir verfassten Buchkapitel und Artikel zum Thema. Dabei gibt es einige Indizien, die gegen die Echtheit dieses Dokuments sprechen. Es ist höchste Zeit, diese einmal zusammenzufassen.

Das Dorabella-Kryptogramm

Wer es noch nicht weiß: Das Dorabella-Kryptogramm stammt (angeblich) von dem britischen Komponisten Edward Elgar (1857-1934). Dessen bekannteste Komposition ist das Stück “Land of Hope and Glory” aus dem Jahr 1902, das als manchmal auch als inoffizielle britische Nationalhymne verwendet wird:

Wie viele andere Musiker interessierte sich Elgar für Kryptologie. 1897 schrieb der damals noch unbekannte Komponist (angeblich) einen Brief an eine 17 Jahre jüngere Freundin namens Dora Penny. Diesem Schreiben legte er einen Zettel mit einer kurzen verschlüsselten Botschaft bei:

Erstaunlicherweise ist es bisher niemandem gelungen, diese an eine in kryptologischen Fragen nicht bewanderte Person gesendete Nachricht zu knacken. Inzwischen gehört das Dorabella-Kryptogramm zu den weltweit bekanntesten ungelösten kryptologischen Rätseln überhaupt und damit auch in meine Liste der bekanntesten Kryptogramme.

Meine Transkription des Dorabella-Kryptogramms sieht wie folgt aus (leider ist die Handschrift an einigen Stellen nicht ganz eindeutig):

ABCDE FGDHA IJKLJ MJJFB BJNGO GNIP

GJGFQ DHRSC JJCFN KGJIJ FTPKL QHHQI P

CPFUP CLUZN PCJFU KPNDB NPFDL ED

Der verschlüsselte Text umfasst 87 Zeichen ohne Zwischenräume, die sich über drei Zeilen erstrecken. Es gibt 24 unterschiedliche Zeichen. Jedes davon setzt sich aus einem, zwei oder drei Bögen zusammen. Das J ist der häufigste Buchstabe, gefolgt vom F und vom P.

Über den Inhalt der Dorabella-Nachricht ist leider nichts bekannt. Dem Anschein nach handelt es sich um eine Mitteilung für Dora Penny und war dazu gedacht, von dieser entschlüsselt zu werden.

Das Dorabella-Kryptogramm ist auch als Aufgabe bei MysteryTwister C3 gelistet. Im Internet kursieren mehrere angebliche Lösungen, die jedoch keine Anerkennung gefunden haben.

Eine Fälschung?

Soweit der bekannte Teil. Doch warum könnte es sich beim Dorabella-Kryptogramm um eine Fälschung handeln? Einige Günde dafür konnte man bereits auf diesem Blog nachlesen. Diese Ausführungen stammen jedoch nicht von mir, sondern von Cipherbrain-Leser Thomas Ernst.

Ernst hat seine Ausführungen dankenswerterweise in sehr ausführlichen Kommentaren auf meinem Blog veröffentlicht:

Thomas Ernst plant nach eigener Aussage eine Fachveröffentlichung zu diesem Thema. Es ist wohl unnötig zu erwähnen, dass ich darauf sehr gespannt bin. Im Folgenden will ich die wichtigsten Punkte, die für eine Fälschung sprechen, zusammenfassen.

Meiner Meinung nach gibt es vor allem drei Indizien, die zu nennen sind.

Indiz 1: Die Provenienz

Die Provenienz (also die Geschichte eines Objekts) ist ein wichtiges Kriterium bei der Beurteilung, ob ein Objekt echt ist.

Betrachtet man die Geschichte des Dorabella-Kryptogramms, dann fällt zunächst auf: Es gibt für das Kryptogramm nur eine Quelle: das Buch “Edward Elgar: Memories of a Variation” von Dora Powell (geb. Penny). Dieses Werk erschien 1937 und damit drei Jahre nach dem Tod des Komponisten. Es gibt keinen Beleg dafür, dass das Kryptogramm zu Elgars Lebzeiten bereits existierte, geschweige denn, dass dieser es 1897 verfasste.

Es könnte also durchaus sein, dass Dora Powell das Dorabella-Kryptogramm selbst erstellt (sprich: gefälscht) hat, um ihr Buch damit spannender zu machen.

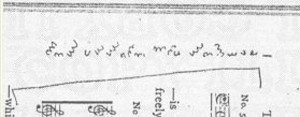

Es gibt außerdem zwei verschlüsselte Notizen, die Edward Elgar angefertigt haben soll und die dem Dorabella-Kryptogramm ähneln. Sie sind (im Gegensatz zum Dorabella-Kryptogramm) erhalten geblieben. Hier ist eine davon:

Eine Möglichkeit wäre, dass Dora Powell diese Notizen kannte und als Vorbild für die Fälschung verwendete. Thomas Ernst meint jedoch, dass Powell auch die beiden Notizen fälschte, um das Kryptogramm glaubwürdiger erscheinen zu lassen. Dies ist durchaus möglich, denn Powell hatte nach Elgars Tod Zugang zu den entsprechenden Unterlagen, als diese an ein Museum übergeben wurden.

Indiz 2: Buchstaben-Ersetzung scheidet aus

Die Häufigkeitsverteilung der 24 Zeichen im Dorabella-Kryptogramm deutet auf eine einfache Buchstabenersetzung hin. Alle Versuche, das Rätsel mit diesem Ansatz zu lösen, sind jedoch bisher gescheitert.

Denkbar wäre, dass Elgar besondere Wörter oder ungewöhnliche Schreibweisen verwendet hat. In einem seiner Notizbücher ist der Satz DO YOU GO TO LONDON TOMORROW? zu lesen, der viele Os, dafür aber kein E enthält – für einen Codeknacker sehr verwirrend. Gleiches gilt für den Satz “warbling wigorously in Worcester wunce a week”, der von Elgar stammt.

Um dieser Hypothese nachzugehen, untersuchte ich das Dorabella-Kryptogramm vor drei Jahren mit zwei Methoden, die in einem Text die Konsonanten bzw. Vokale identifizieren. Dabei handelt es sich um die Konsonantenlinien- und die Vokalerkennungsmethode (die Namen der Verfahren sind nicht besonders einfallsreich gewählt, was ihre Qualität aber nicht beeinträchtigt). Beide Verfahren werden in dem Buch “Cryptanalysis” von Helen Fouché Gaines beschrieben.

Die Ergebnisse waren eindeutig: Während beide Methoden bei einem Vergleichstext bestens funktionierten, lieferten sie beim Dorabella-Kryptogramm keine brauchbaren Ergebnisse. Dies ist ein starkes Indiz dafür, dass dem Dorabella-Kryptogramm keine Buchstaben-Ersetzung zugrunde liegt. Es muss also entweder eine kompliziertere Chiffre oder eben gar keine verwendet worden sein.

Dies ist zwar kein Beweis, stärkt aber die von Thomas Ernst vorgebrachte Vermutung (siehe nächstes Unterkapitel), Dora Powell habe das Kryptogramm wahllos zusammengewürfelt.

Indiz 3: Schreibvorliebe statt Linguistik

Thomas Ernst kommt in einem seiner Kommentare zu dem Schluss, dass die Symbolfolgen im Dorabella-Kryptogramm Muster aufweisen, die linguistisch kaum erklärbar sind, dafür aber durch Powells Schreibvorlieben erklärt werden können:

Staying mindful of the original, one can transcribe a) the angle and b) the number of semicircles as 0-1, 0-2, 0-3, 45-1, 45-2, 45-3 etc. With a straight “E” as starting point, it makes sense to indicate this angle with “0” instead of “360”. Ultimately, it doesn’t matter. I found it useful to summarize the symbols as follows: angle in first position, amount of semicircles in second position, frequency of occurrence following after the “:”, numeric occurrence on either line 1, 2, or 3 following a “/”. A “=” after each symbol indicates its occurrence; the “Total” at the end of the line indicates the total amount of symbols with one, two or three semicircles at that angle. Uncertain angles are in square brackets. E. g. “180-3: 1/2, 20, 21; 3/20 = 4” means: at 180 degrees clockwise, the sign with 3 semicircles appears in line 1 in position (counted from left to right) 2, 20, 21, and in line 3 in position 20, which yields a total for this one sign. The “Total” at the end of “180” – 4 – is the total of all signs at this angle:

• 0-1: 1/5; 3/26 = 2 | 0-2: 1/1 = 1 | 0-3: 1/[4], 8; 2/6, 9; 3/19, 24, 27 = 7 | Total of 10.

• 45-1: 1/14; 2/[25]; 3/[7], [25] = 4 | 45-2: 1/3; 2/10, 13; 3/1, 6, 12 = 6 | 45-3: 1/11, 28; 2/19, 30 = 4 | Total of 14.

• 90-1: 1/23, 27; 2/15; 3/10, 18, 21, 25 = 4 | 90-2: 1/6, 19; 2/4, 14, 21; 3/3, 14, 23 = 8 | 90-3: 1/16 = 1 | Total of 16.

• 135-1: 1/9; 2/7, 27, 28 = 7 | 135-2: 2/8 = 1 | 135-3: – = 0 | Total of 5.

• 180-1: –; 180-2: – | 180-3: 1/2, 20, 21; 3/20 = 4 | Total of 4.

• 225-1: 1/13; 2/16, 24; 3/16 = 4 | 225-2: 1/12, 15, 17, 18, 22 = 5 | 225-3: 1/29; 2/23, 31; 3/2, 5, 11, 17, 22 = 8 | Total of 17.

• 270-1: 1/7; 2/1, [3], 5, 17 = 5 | 270-2: 2/22; 3/4, 8, 15 = 4 | 270-3: 3/9 = 1 | Total of 10.

• 315-1: 1/26; 2/26, 29 = 3 | 315-2: 1/10, 25 = 2 | 315-3: – | Total of 5.

If you look at the distribution and amount of certain signs, it becomes apparent that neither can be dictated by an underlying monoalphabetic principle, but that their existence or avoidance is dictated graphologically: DP had difficulty writing at certain angles, independent of whether the sign had one, two, or three semicircles, 180 and 315 degrees being the most obvious. Distribution-wise, DP also has her preferences, to wit two semicircles at 90 degrees: four times in line 1, eight (!) times in line two, but once in line 3. Add the following to the distribution: typically, DP repeats a symbol after 7 or 8 different symbols. This is a rather amateurish way of faking a cipher: make as many symbols different from the previous, before repeating one. That is one of the reasons why no one as of yet has found suitable words without tuning the English language into gibberish. – The third, sagging line appears to have been added later, because it has a different symbol distribution from lines one and two. – Since the American music critic Irving Kolodin put the “Dorabella Cipher” into the lime light in the 1950s, there have been repeated suggestions that this “cipher” may contain music. Pray tell: how so???

Fazit

Die hier vorgebrachten Indizien sind natürlich keine Beweise. Ingesamt halte ich eine Fälschung durch Dora Powell allerdings für durchaus möglich.

Jetzt würde mich die Meinung meiner Leser zu diesem Thema interessieren.

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Further reading: Richard Bean solves another Top 50 crypto mystery

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13501820

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/763282653806483/

Kommentare (14)