According to a recent BBC article, a British student has broken a “religious code” from the 18th century. What is behind it?

Blog reader Ralf Bülow has thankfully made my aware of an article published on the BBC news site. It starts as follows: “A divinity student from the University of St Andrews has cracked a religious code that has baffled academics for generations.”

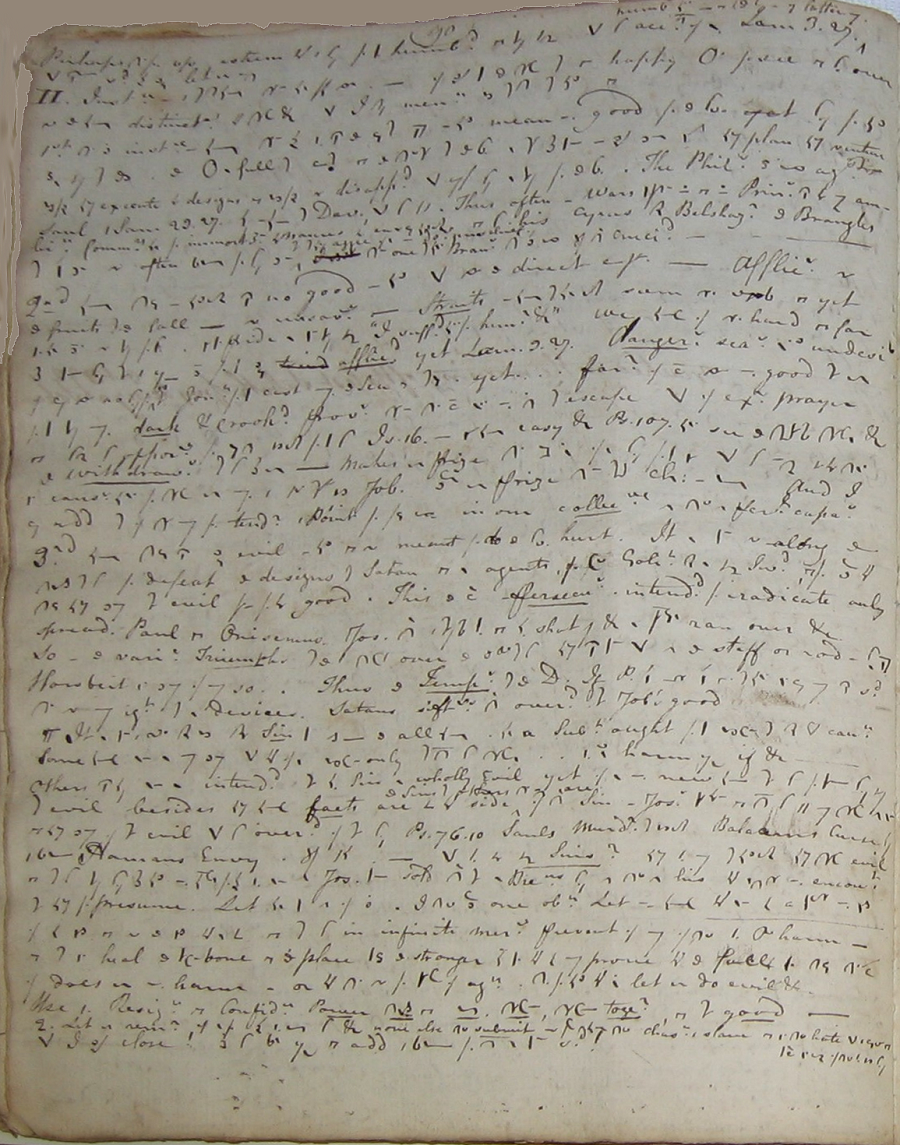

Fuller’s sermon book

It goes without saying that I was immediately thrilled when I read about this story – cryptograms that baffle cryptanalysts are exactly what I like to write about most on this blog. In addition, some of the most outstanding cryptograms known to me (including the Rohonc Codex, James Hampton’s notebook, and the Anthon transcript) have a religious background. And most of all, the ciphertext covered in the BBC article was completely new to me, although I know pretty many ciphertexts that have baffled experts for a long time. Apparently, this one is not mentioned in the crypto history literature.

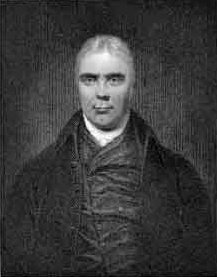

The cryptogram in question was created by English Baptist preacher Andrew Fuller (1754-1815). Fuller pubished a number of influential works, including theologic treatises, pamphlets, sermons, and essays.

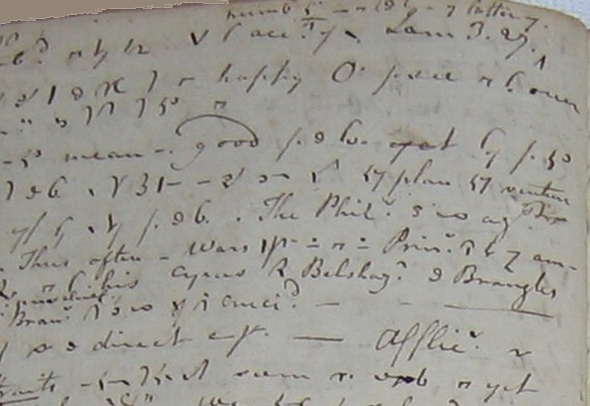

Fuller left behind a book mostly written in a code. I included this work in my encrypted book list at position 00096. According to the BBC article, Fuller’s code could not be read for centuries. The article depicts two pages of the book. Here’s the first one:

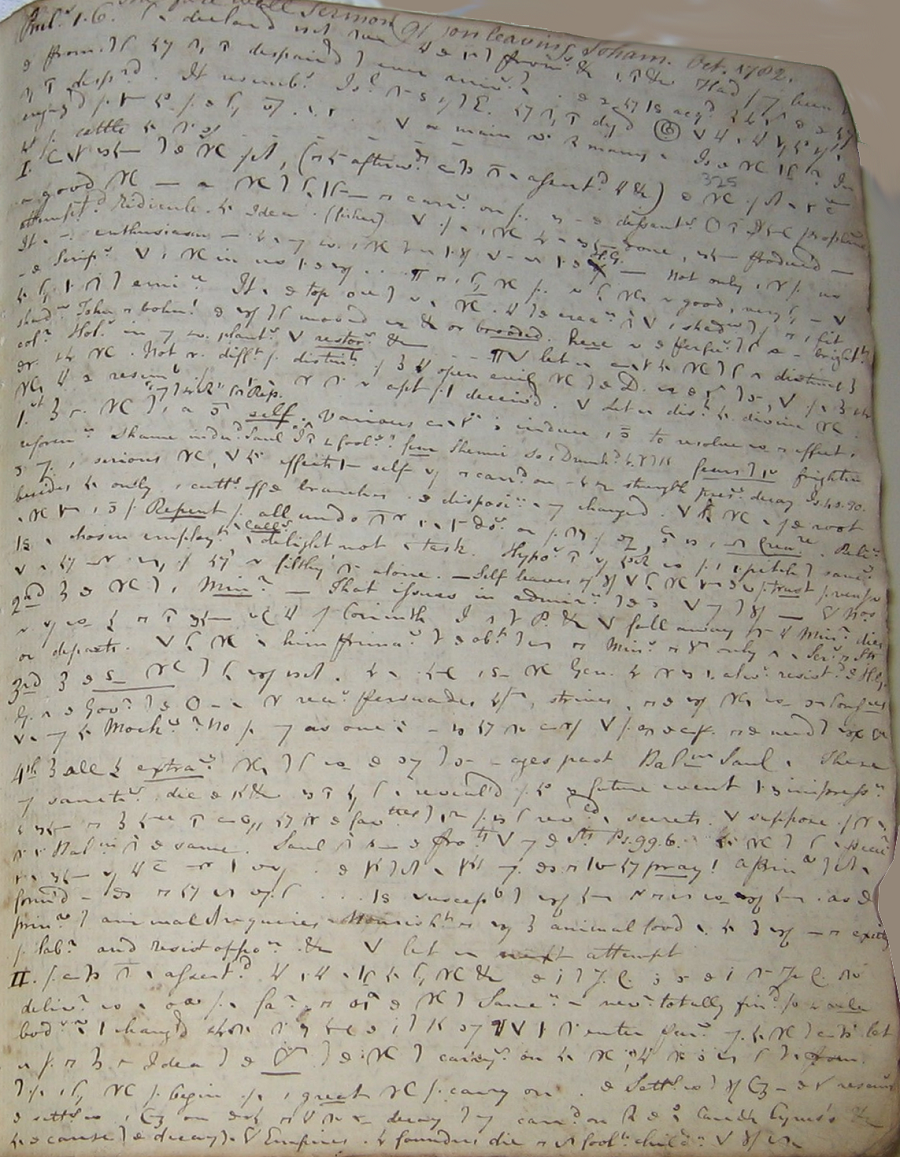

Here’s the second one:

As can be seen, the encoding system Fuller used is a shorthand. I am always a little reluctant to blog about shorthands, as this kind of writing is not really encryption. Shorthands were not invented to keep a message secret but to make writing faster. Anyway, they were often used for low-grade encryption.

I don’t know if Andrew Fuller had a reason to keep his sermons secret or if he used a shorthand to write more quickly (or both). Anyway, when modern researchers became interested in Fuller’s sermon book, they could not read it. I don’t know if this book really “baffled academics for generations”, as the BBC article says, but it is clear that an 18th century shorthand is hard to read. This is because there were many different shorthands in existence, and shorthands have changed over the centuries.

The solution

According to the article, it was Dr. Steve Holmes, head of the School of Divinity at St Andrews University in Scotland, who made the break-through in deciphering Fuller’s book. Holmes found a passage headed “Confessions of Faith, Oct. 7 1783” written in the clear. Apparently, this passage contained the confession of faith, which could be used as a crib.

Holmes recruited student Jonny Woods, who tried to decipher Fuller’s book based on Holmes’ preparatory work. After just a few weeks, he was able to read the shorthand. Meanwhile, two of Fuller’s sermons are decoded. The article doesn’t say anything about the content of these sermons, but most codebreakers don’t care about the content of a deciphered message anyway.

I hereby congratulate Steve Holmes and Jonny Woods on this cryptanalytic success. I have sent Holmes a mail and encouraged him to submit a paper for HistoCrypt. To my regret, he doesn’t have the time to attend.

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Further reading: Who can decrypt this shorthand postcard from 1904?

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13501820

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/763282653806483/

Kommentare (3)