English version (translated with Deepl)

Im September 2017 habe ich über eine verschlüsselte Nachricht gebloggt, die 1939 von der Schleswig-Holstein, einem deutschen Schlachtschiff, an eine private Adresse in Kiel verschickt wurde. Dieses Kryptogramm wurde bisher nicht gelöst. Dank Blog-Leser Patrick Hayes gibt es zu diesem Krypto-Rätsel nun (ziemlich umfangreiche) neue Informationen.

Die Schleswig-Holstein

Die Schleswig-Holstein wurde von 1905-1908 gebaut. Sie kämpfte in beiden Weltkriegen. Im Ersten Weltkrieg kam sie in der Jütlandschlacht zum Einsatz. Als eines der wenigen Schlachtschiffe, die der Versailler Vertrag für Deutschland zuließ, wurde die Schleswig-Holstein in den Zwanziger-Jahren wieder militärisch genutzt. Im Jahr 1935 wurde sie zum Schulschiff umgebaut. Den größten Teil des Zweiten Weltkriegs wurde die Schleswig-Holstein zu diesem Zweck eingesetzt, bevor sie im Dezember 1944 von britischen Bombern versenkt wurde.

Die Schleswig-Holstein feuerte die ersten Schüsse des Zweiten Weltkriegs ab, als sie am Morgen des 1. September 1939 die Westerplatte in Danzig unter Beschuss nahm.

Das erste Schleswig-Holstein-Kryptogramm

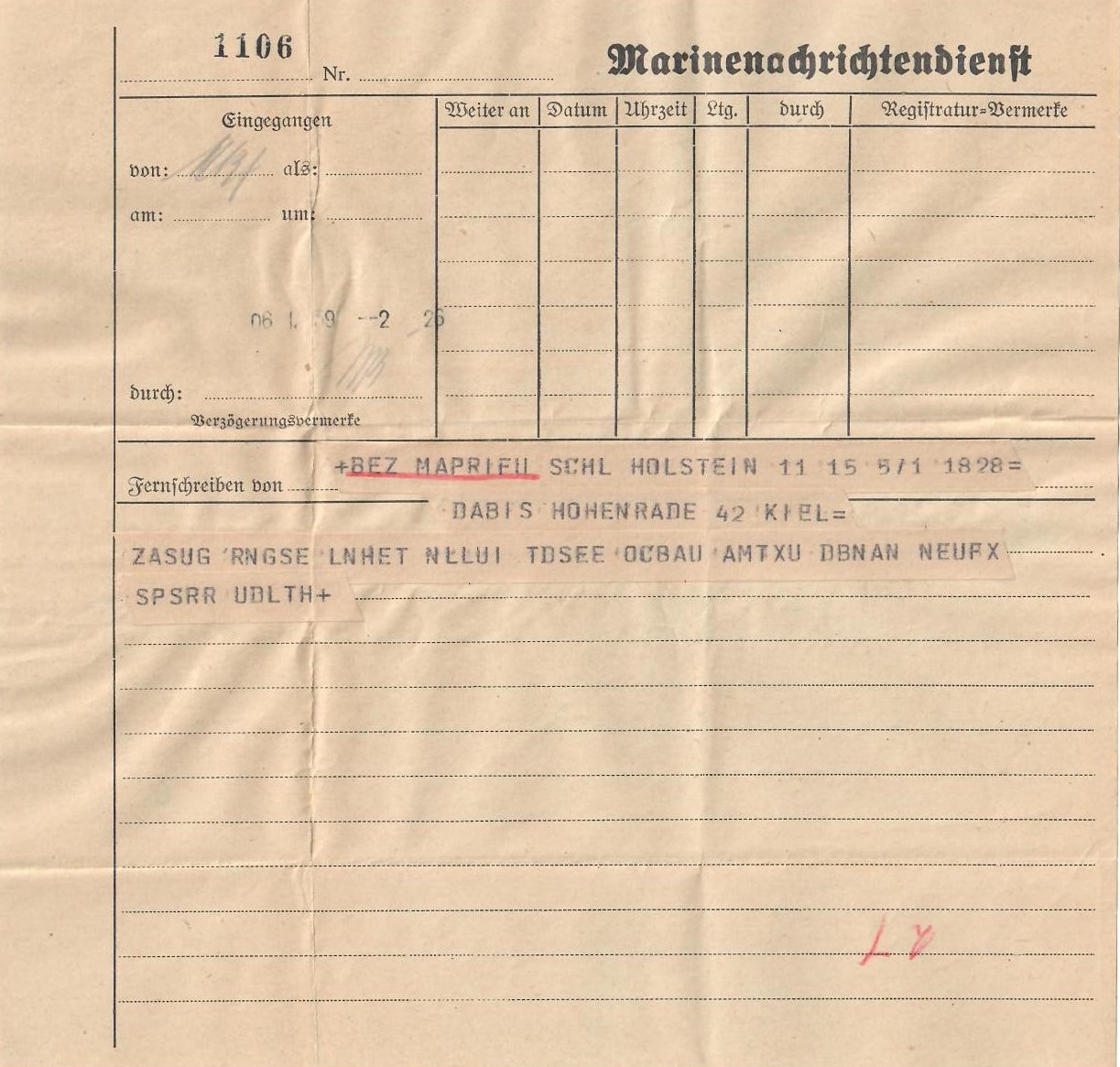

Mein Freund Tobias Schrödel, den meine Leser als Comedy-Hacker, Buchautor, Stern-TV-Experte und Krypto-Buch-Experte kennen, hat mir vor ein paar Jahren ein interessantes Dokument zur Verfügung gestellt: ein verschlüsseltes Fernschreiben, das am 6. Januar 1939 von der Schleswig-Holstein an eine Adresse in Kiel verschickt wurde (siehe hier). Hier ist ein Scan dieses Schreibens:

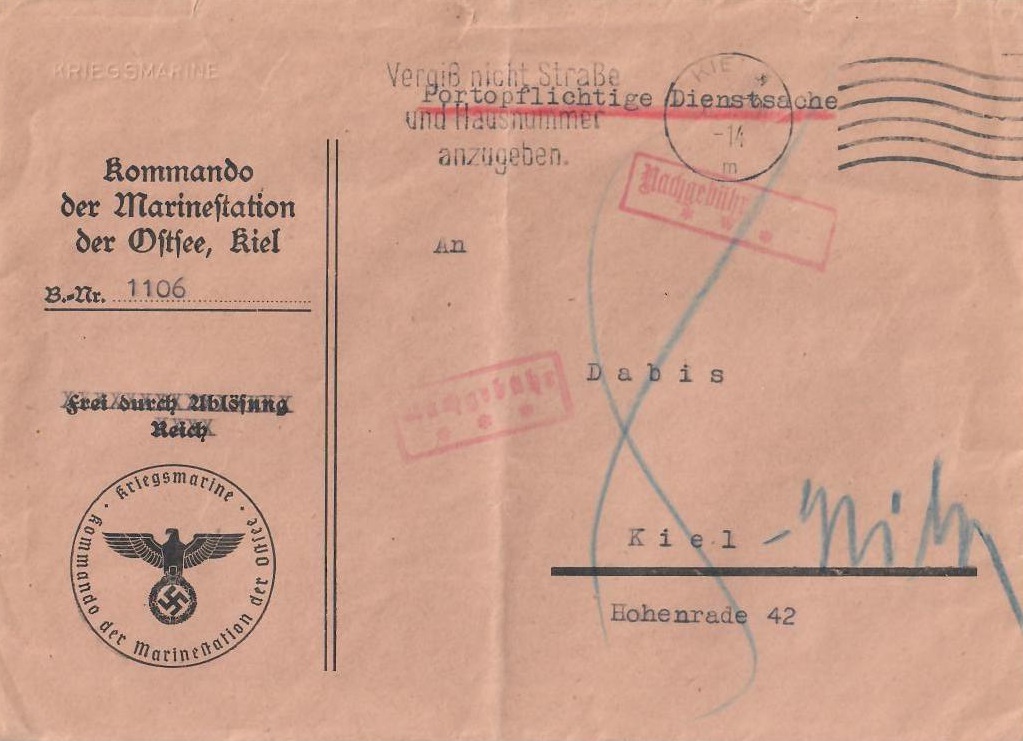

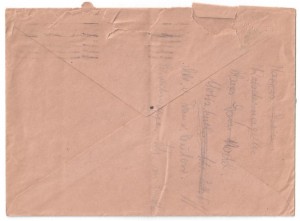

Diese Botschaft (“Schleswig-Holstein-Kryptogramm”) war in folgendem Briefumschlag enthalten:

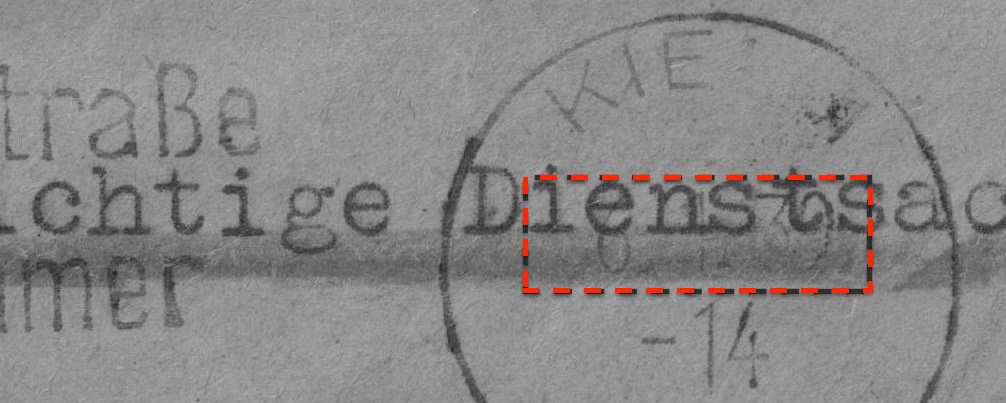

Empfänger dieser Sendung war eine Person oder Familie namens Dabis in Kiel. Der Nachname Dabis ist zwar selten in Deutschland, kommt aber in Kiel vor. Das Datum (6. Januar 1939) ist auf dem Umschlag zu erkennen, worauf mich Tobias Schrödel dankenswerterweise hingewiesen hat:

Auf der Rückseite des Briefs hat der Empfänger anscheinend eine Einkaufsliste notiert:

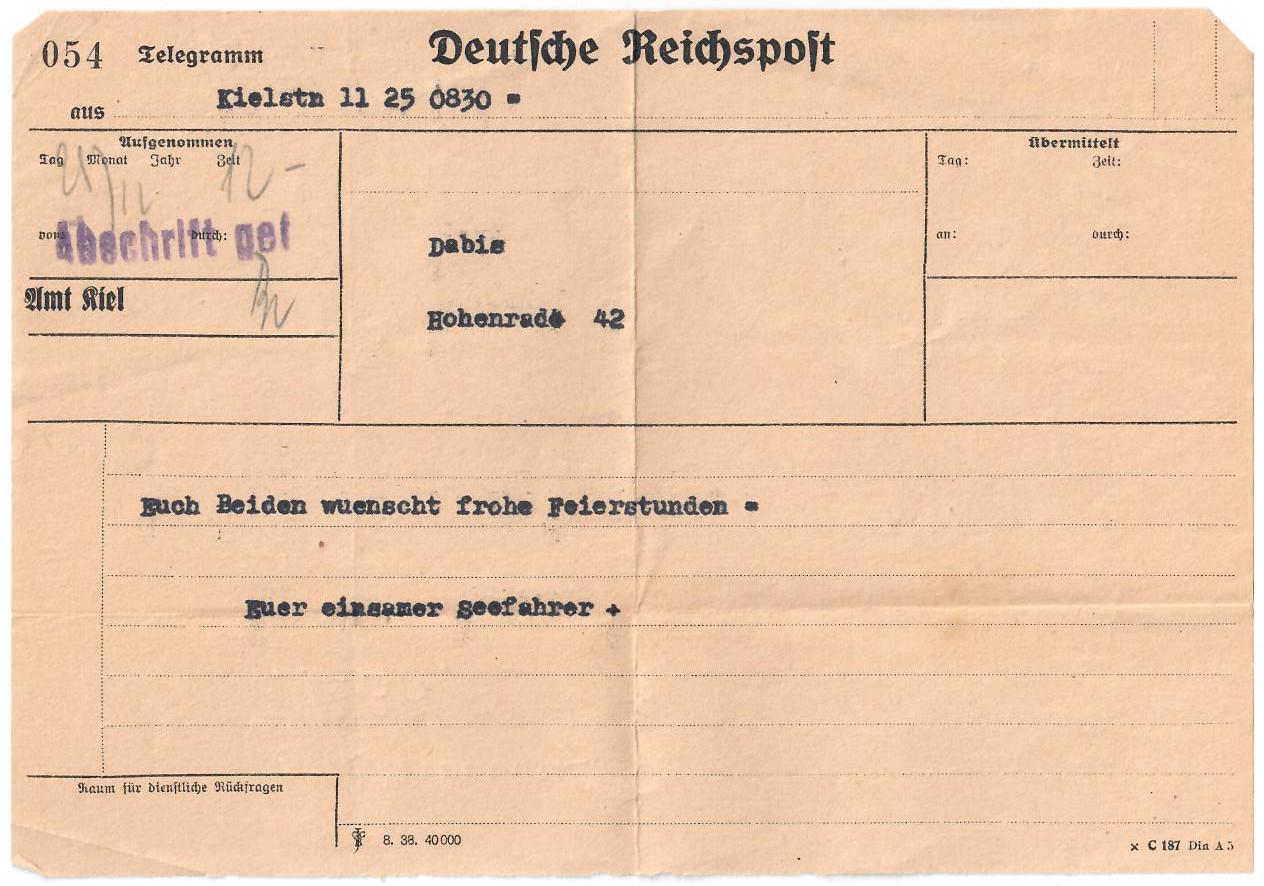

Im Umschlag befand sich noch ein weiterer Zettel. Es handelt sich um ein unverschlüsseltes Telegramm mit einem Weihnachtsgruß, das bereits einige Monate zuvor (am 24.12.1938) an die gleiche Adresse gesendet wurde:

Ich gehe davon aus, dass dieses Telegramm ursprünglich nicht im Briefumschlag enthalten war. Vermutlich wurde es lediglich vom Empfänger in diesem gelagert (soweit ich weiß, wurden Telegramme üblicherweise ohne Briefumschlag ausgeliefert).

Das Schleswig-Holstein-Kryptogramm lässt sich wie folgt transkribieren:

ZASUG RNGSE LNHET NLLUI TDSEE OCBAU AMTXU DBNAN NEUFX SPSRR UDLTH+

Patrick Hayes

Über das ICCH-Forum habe ich letztes Jahr Patrick Hayes …

… kennen gelernt. Patrick, der eine interessante Webseite zum Thema Verschlüsselungsmaschinen betreibt, hat mir folgendes über sich geschrieben:

Patrick Hayes is a specialist and collector of cryptologic artefacts. He also brokers cryptologic artefacts linked to the Enigma, T-52 Geheimschreiber and other cipher machines to museums, dealers and collectors across Europe and North America. He is director of the Chiffriermaschine Museum, a virtual crypto history museum available at www.chiffriermaschine.com and is a member of the International Conference of Cryptologic History (ICCH). He is also currently studying History at Durham University, in the UK.

ICCH-Vorträge (sie werden auf Englisch gehalten und per Zoom übertragen) finden übrigens alle zwei Wochen samstags statt. Demnächst soll es eine Webseite dazu geben. Die Teilnahme-Links werden aus Sicherheitsgründen bisher nicht im Internet veröffentlicht. Jeder ist willkommen, und die Teilnahme ist kostenlos. Wer dabei sein will, kann mir gerne eine Mail schicken.

Drei weitere Schleswig-Holstein-Kryptogramme

Patrick Hayes hat mir kürzlich drei weitere verschlüsselte Nachrichten zukommen lassen, die von der Schleswig-Holstein an die Dabis-Adresse in Kiel geschickt wurden. Zusätzlich hat er mir weitere (unverschlüsselte) Korrespondenz aus derselben Quelle zur Verfügung gestellt. Insgesamt sind dies nicht weniger als 153 Seiten – ein wahrer Schatz, den Patrick wie folgt beschreibt:

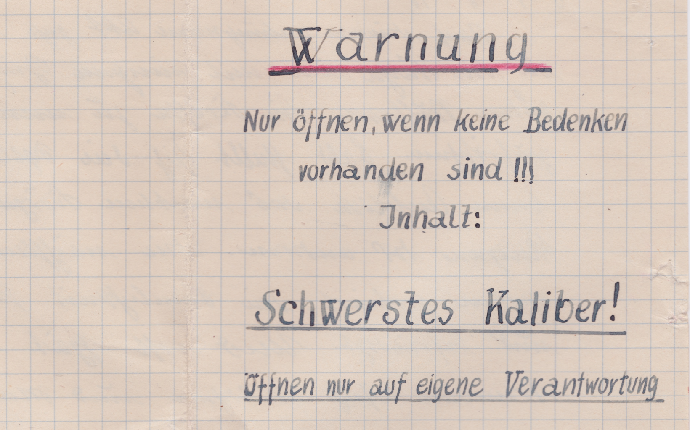

Leider kann ich nicht die gesamte Sammlung in einem Blog-Artikel veröffentlichen. Alle 153 Seiten gibt es jedoch hier zum Download. Interessant ist zweifellos folgende Warnung (S. 6):

Kann ein Leser etwas dazu sagen? Ist dies ironisch gemeint?

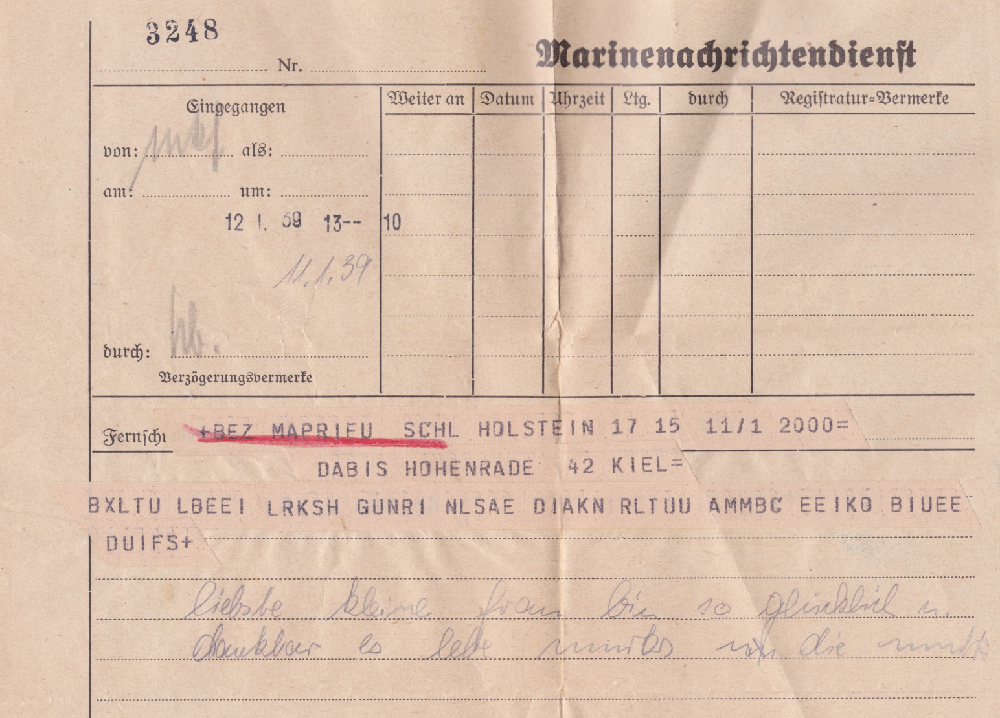

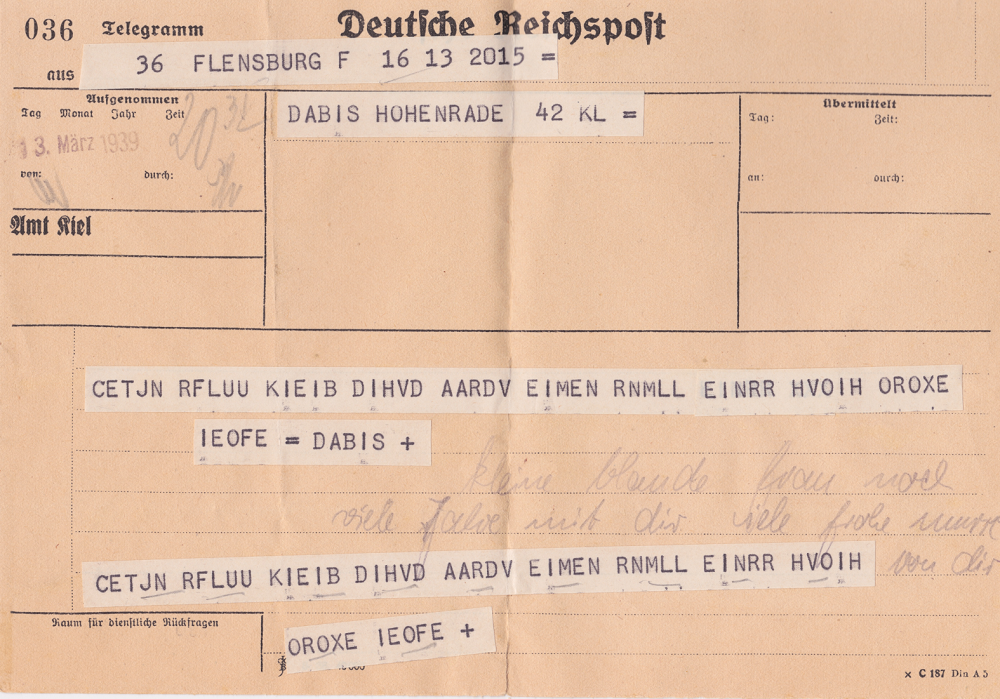

Hier ist die erste verschlüsselte Nachricht aus Patricks Fundus (also das zweite Schleswig-Holstein-Kryptogramm):

Es folgt Schleswig-Holstein-Kryptogramm Nummer 3:

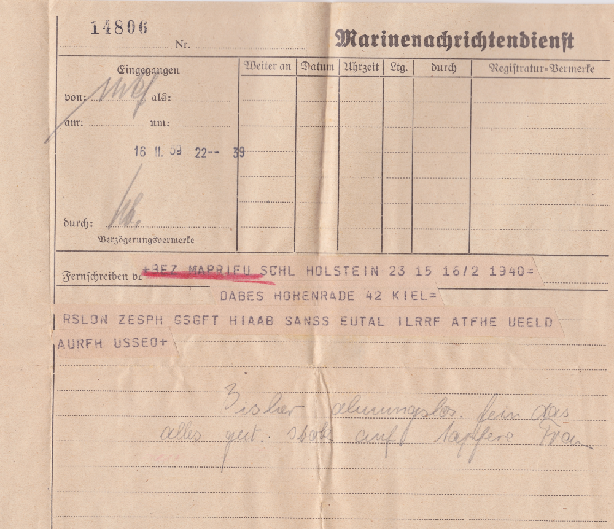

Und schließlich der bisher letzte Geheimtext aus dieser Serie:

Schafft es jemand, diese vier Kryptogramme zu dechiffrieren?

Nach meinem ersten Artikel zum Thema gab es eine umfangreiche und sehr interessante Diskussion. Jim Gillogly, ein hervorragender Codeknacker meinte, es könnte eine Transpositionschiffre verwendet worden sein. Ein professionelles Verfahren – etwa ein Codebuch oder eine Verschlüsselungsmaschine – erscheint dagegen eher unwahrscheinlich.

Vielen Dank noch einmal an Tobias Schrödel und Patrick Hayes für diese spannende Kryptogramm-Serie!

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Further reading: An encrypted letter from World War 2

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13501820

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/763282653806483/

Kommentare (30)