Unsolved ciphertexts from World War II (1)

Here are five examples of unsolved ciphers from World War II. There are more. Can my readers help me complete my list?

To my knowledge, no one has ever compiled a list of unsolved cryptograms from World War II. Thereby there are quite a number of such crypto puzzles, some of which I have already presented on my blog. I therefore want to compile such a list. I start today with five examples and also present a first draft list, which I would like to expand with the help of my readers.

1. The ciphertext in the bullet

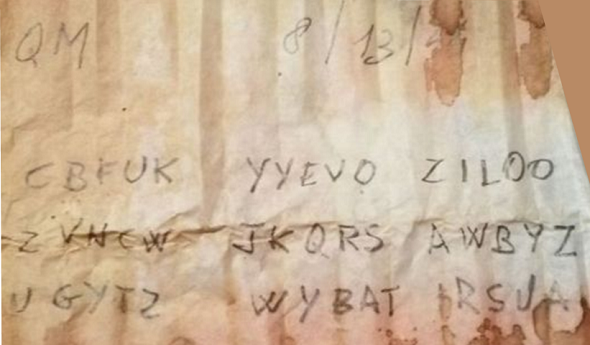

In the soil of southern Tuscany, as reported in an article published in 2015, a few years ago a prospector made an interesting discovery: a coded note from World War II. This was hidden in a cartridge (that’s why the metal probe struck). This is what the note looks like:

The cryptogram transcribes as follows:

CBFUK YYEVO ZILOO

ZVNCW JKQRS AWBYZ

UGYTZ WYBAT RSUA

605YZ/FF

To my knowledge, this encrypted message is still unsolved. I don’t know too many sources and researches about it either. I blogged about it in German in 2015 and in English in 2017.

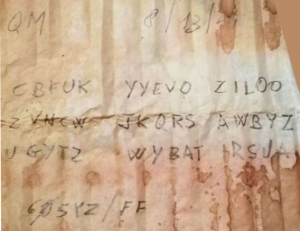

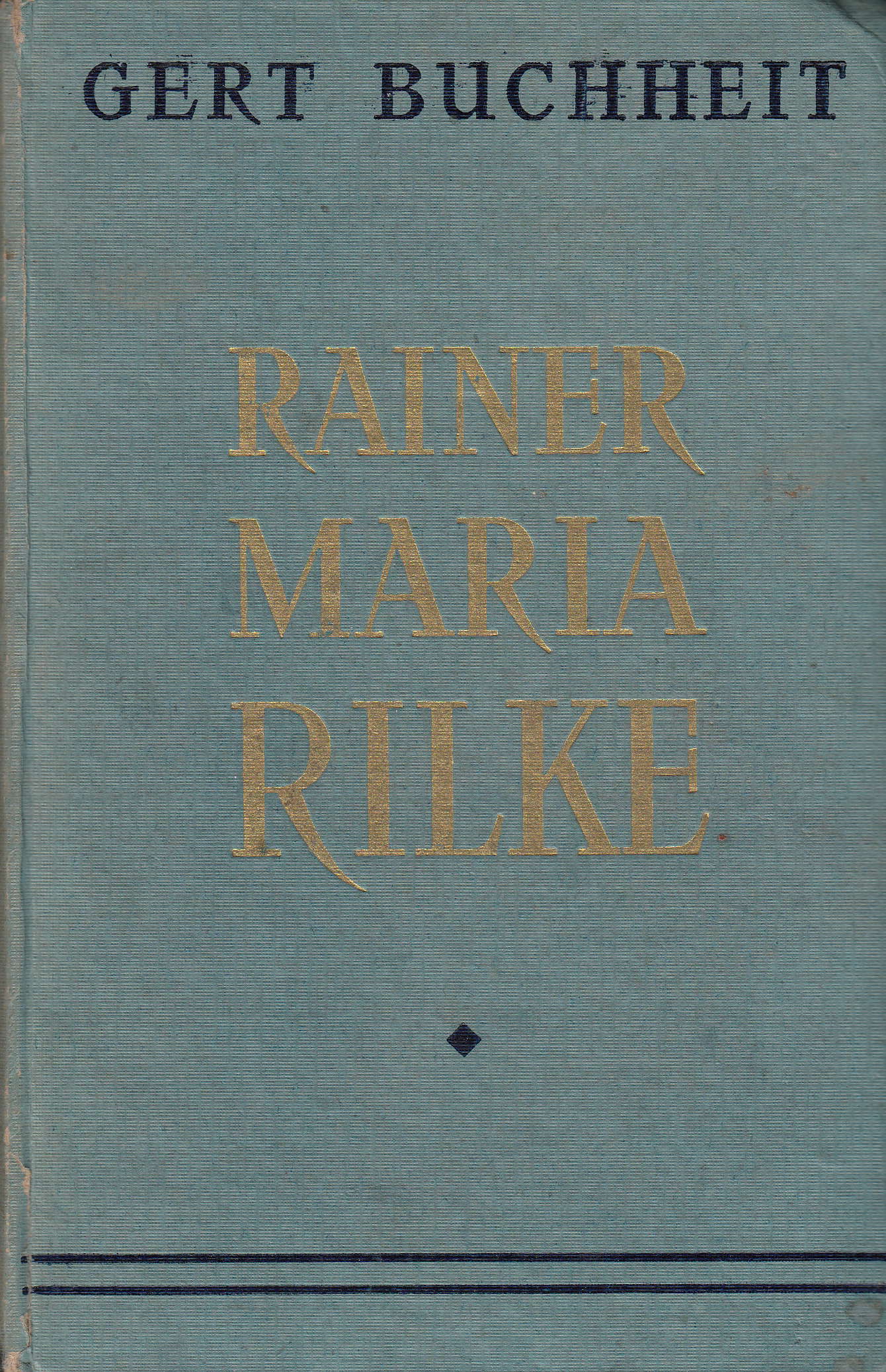

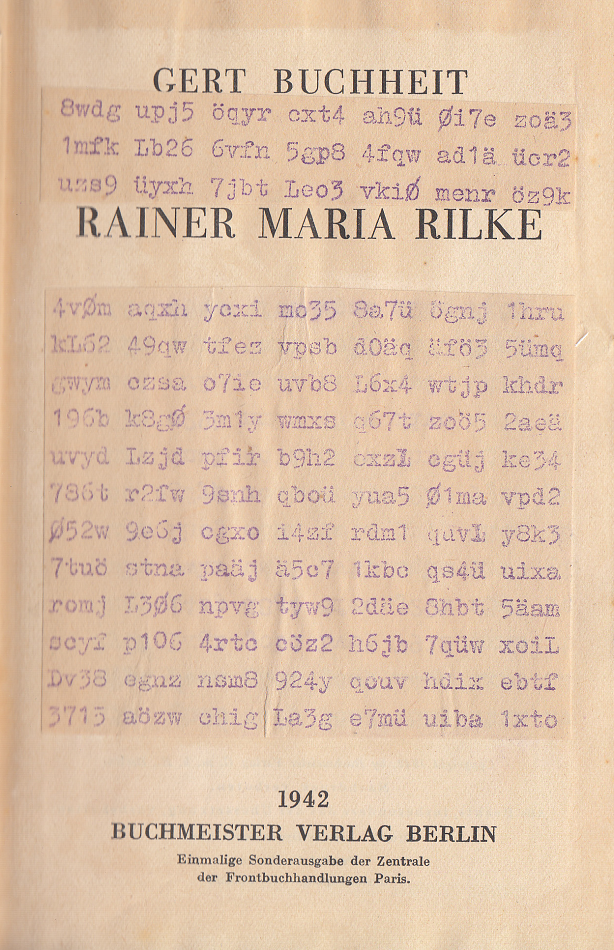

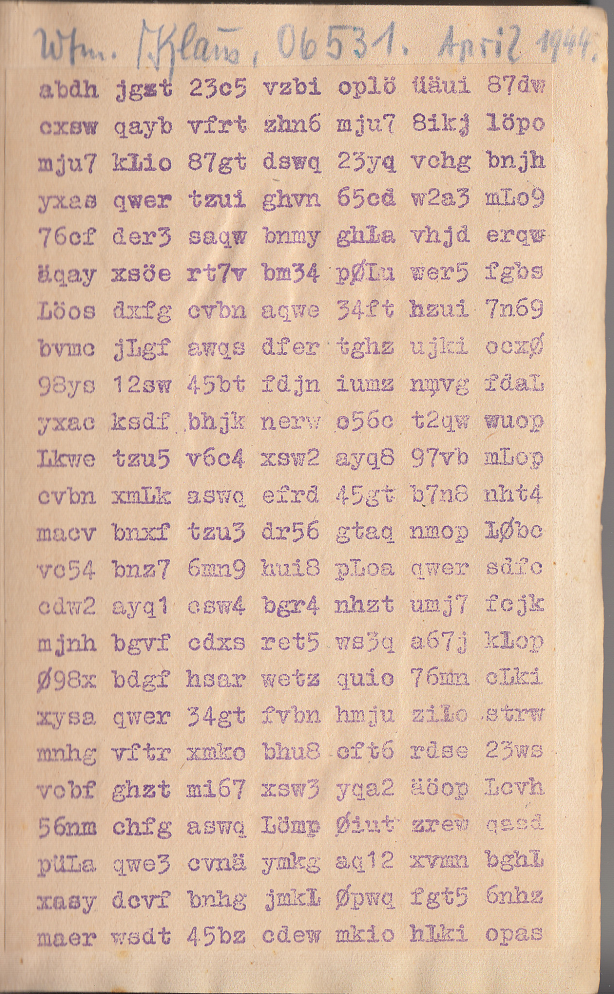

2. The Rilke cryptogram

Blog reader Karsten Hansky provided me with this extremely interesting encryption puzzle. It is in a copy of the book “Rainer Maria Rilke” by Gert Buchheit. This book dates from 1928. The edition in question was published in 1942 by Buchmeister Verlag in Berlin, as a “One-time special edition of the headquarters of the front bookstores Paris”.

The special thing about this copy: The former owner (or whoever) pasted several dozen slips of paper into the book, each with a coded text on it. Virtually every free space in the book was used for this purpose. No book text was pasted over. For example, this is what the first printed page looks like:

Even before this printed page, on the back of the title page, there is the only handwritten entry besides the obligatory coded note:

More pages from the book (“Rilke cryptogram”) can be seen on a page I have set up for this purpose. I have also included the Rilke cryptogram in my list of encrypted books – with the number 00063.

An interesting question now is: what was the purpose of this book? Is it an encrypted message to a spy? The fact that the message was hidden in a book speaks for it. However, the fact that there is an owner’s note with name, rank and probably field post number speaks against it. In addition, a secret service would probably have made the hiding place a bit more professional (thinner paper, smaller letters, no notes on the first pages).

Another explanation would be that this is a training text for the operator of a teletype or similar device. If that were true, the text would probably be indecipherable.

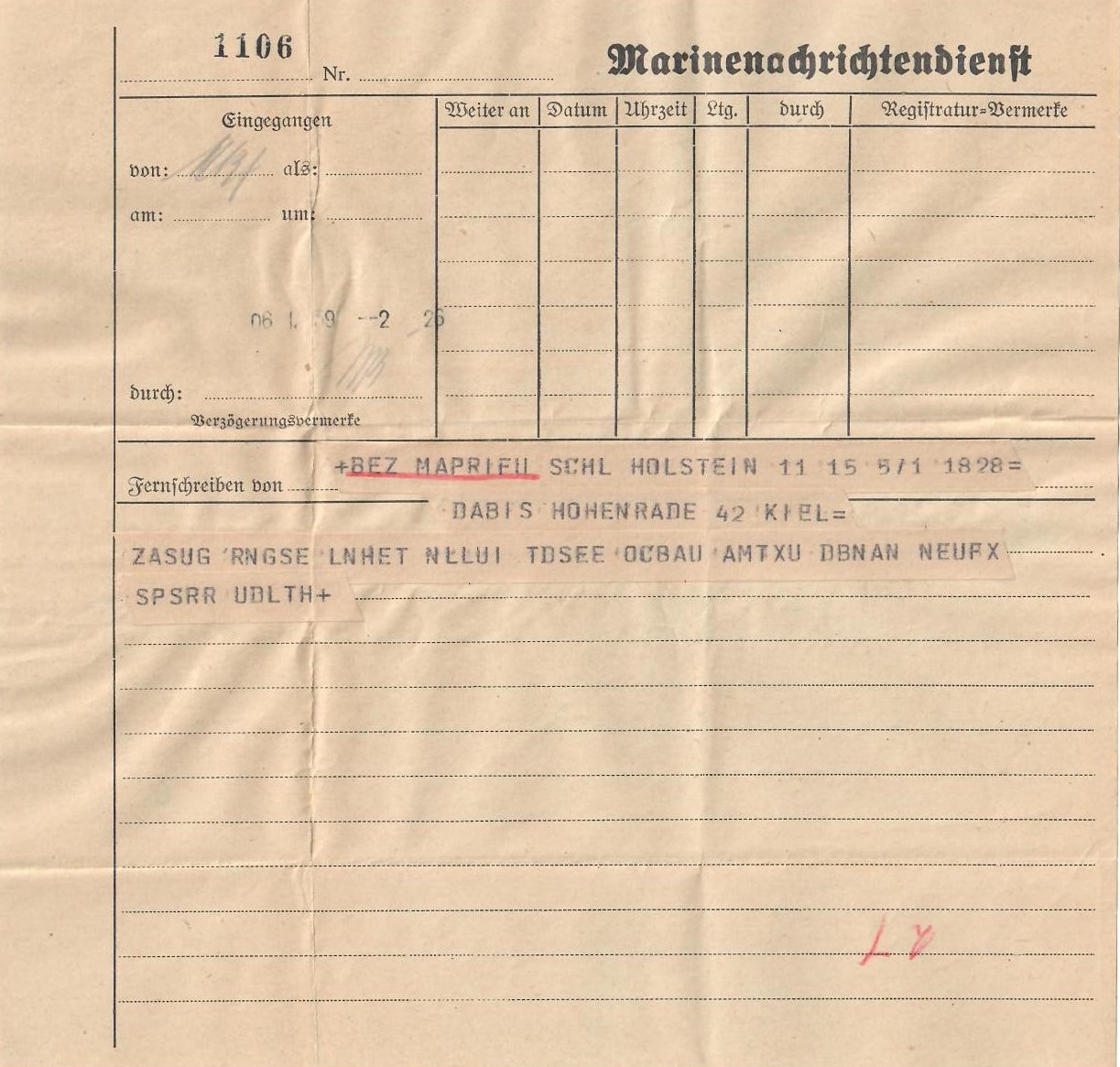

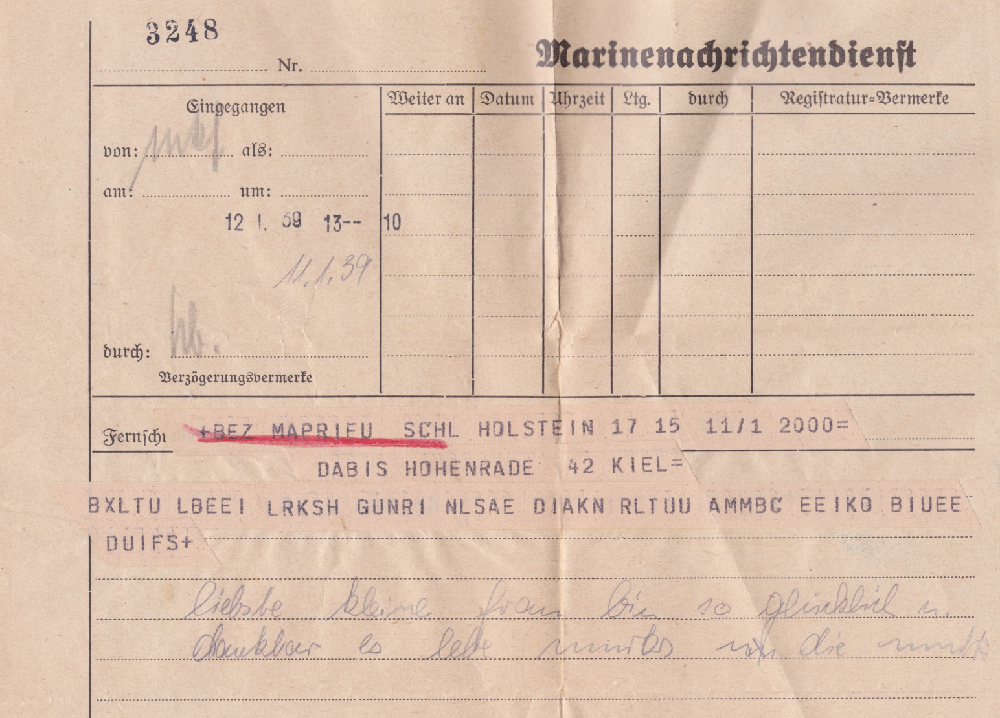

3. The Schleswig-Holstein telegrams

The Schleswig-Holstein, a German battleship, fought in both World Wars. In World War I, she saw action in the Battle of Jutland. One of the few battleships allowed by the Treaty of Versailles for Germany, the Schleswig-Holstein returned to military use in the 1920s. In 1935, she was converted into a training ship. For most of World War II, the Schleswig-Holstein was used for this purpose before being sunk by British bombers in December 1944.

Quelle/Source: Wikimedia Commons

Tobias Schrödel provided me with an interesting document a few years ago: an encrypted telex sent from the Schleswig-Holstein to an address in Kiel on January 6, 1939 (see here). Since World War II had not yet started at that time, this cryptogram strictly speaking does not belong in this article, but I don’t want to look at it that narrowly. Here is a scan of this letter:

The Schleswig-Holstein cryptogram can be transcribed as follows:

ZASUG RNGSE LNHET NLLUI TDSEE OCBAU AMTXU DBNAN NEUFX SPSRR UDLTH+

Blog reader Patrick Hayes recently sent me three more encrypted messages sent from the Schleswig-Holstein to the same address in Kiel. In addition, he has provided me with further (unencrypted) correspondence from the same source. In total, these are no less than 153 pages – a real treasure.

Here is the first encrypted message from Patrick’s trove (i.e. the second Schleswig-Holstein cryptogram):

Here is a blog article on the subject. To my knowledge, these encrypted cryptograms are still unsolved.

4. The Köhler cryptograms

As David Kahn reports in his book “Hitler’s Spies”, the Abwehr (that was the name of a German secret service) had recruited a spy in New York who went by the name “Köhler”. What his real name was and who he was is not known. Presumably, Köhler had no access to secret information and therefore drew his knowledge from everyday observations. According to Kahn, he reported, for example, on U.S. officers he met at a hotel bar who blurted out a few things while drunk. Kahn suspects that Köhler was partly under the influence of the FBI, which is why his reports to the Germans may have been doctored.

In his research, Kahn came across five coded messages that came from Köhler and that the Abwehr forwarded internally to Paris in February 1944 (information about the expected Allied invasion was being gathered in Paris). In 1981, Kahn published these five cryptograms in the journal Cryptologia (April/1981 issue). Obviously, no one submitted a solution. After that, this exciting crypto puzzle was hardly appreciated in the literature.

Here is the letter Kahn found (the numbers obviously stand for the length of the respective message):

An Abwehrleitstelle Frankreich Paris Funkstelle Sofort vorlegen! Betr.: Koehler 237 Ybtat mqfvo dvbis prito kecqg kokik kyiwm zuarj alyia qtxvi vxzya szgou skiqn rbqjq nogex ezdnf vusda zurop ixklo cmnbl grdhz swmch kupef pzlej hbord wkkhu vthjk sfwda jepmu izvig kzlau rdrxx mdecs spozv eeeod dlmdz nqmia pidwg xdcyy mvkso hmmii impwq nkipa mljvm sqsbb glevn sktlq tn. 178 Eekao parwo xiavy pejux lhnjh pbqdd vdvxb mdiia gwymn zbivm abuws dwoug djozl ylaug loaea ilihj swjft oetad tjisn avaqn sodwb wzaxe zvoxg xpgzv adurm shvxx xfmuq pdpvq dqwtu fryok xfvcp ydzwm ofwfl uzfne qsslo avl. 137 tziqb lqqxs kinod mbvil sukms syarh mhzvp tvswm ayddg rixyy omfzm ugfzz aznqe ljuyi ygwuo qmdbi vcxgz rmzno pessh gpoyx qqlei xmaoj buugz czfdl yzmkp gsmfm dteze oxmos. 140 dmxkb kqnvh zzeek beoop ygcca yvepv tykmt iykfl zkacv uxiyd kruwy vnjvp xyeqp jpmfo abzpt mjtdy zvzky bjgze vdtyd zeejw zumjp ivsna gsmzq dltxb qjqqj fnpta mqted skijj. 229 fpoxa tijyp qrerq znqst zasnk zarvq hhsmw vlhfg pyhqc yuirf fsgoi twgdg sbphc fkfza bpegh jzujn wtsxp ijamg tzdto hxzdn uivww tizoc axkye lhmdn sfzjo omrhb zpith hkisf anvdr ynhqk syrgi ltxos wabom dzwlb byava sjomn qqszs adddu greao albon lxzgi iwpnf uzgui jgmya ksqfw zsjl.

These messages have not yet been cracked. I assume that Köhler did not use an encryption machine, but only worked with paper and pencil.

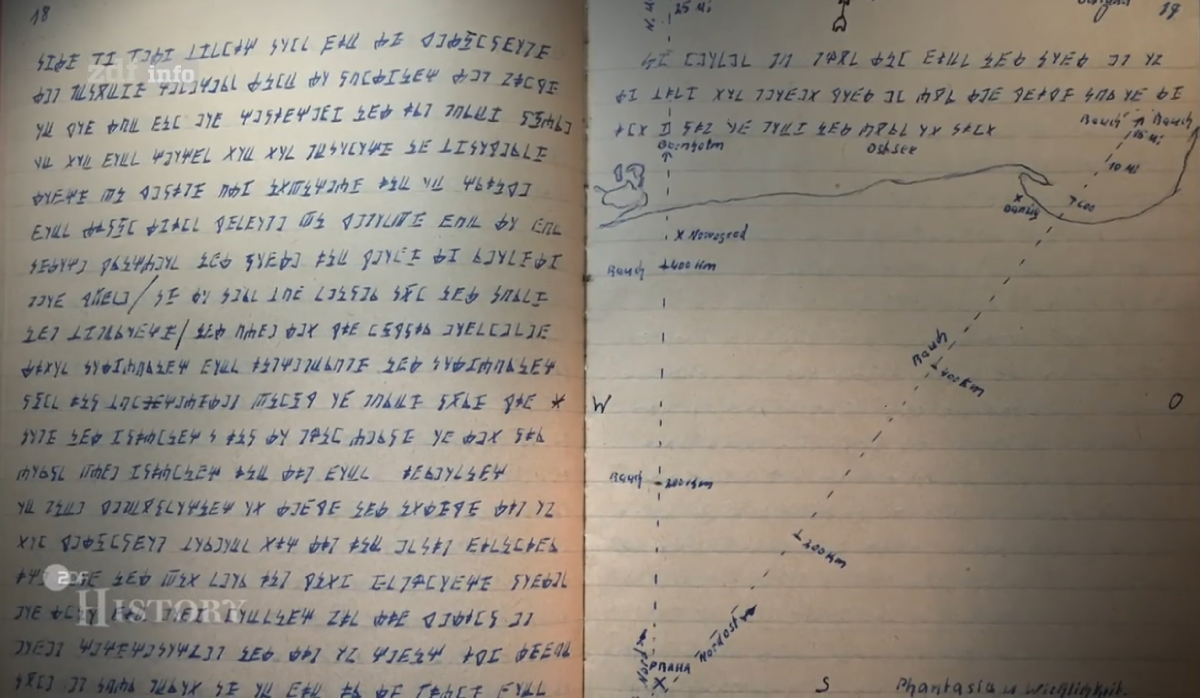

5. A soldier’s notes

Blog reader Matthias Axinger brought a television documentary called “Secret Underworlds of the SS – The Secret of Stechowice” to my attention a few years ago. It is about an SS officer named Emil Klein who was imprisoned in the Czech Republic after the end of World War II. Allegedly, Klein knew something about a secret Nazi tunnel system near Stechowice, a town south of Prague. Rumor has it that the Nazis hid gold and other valuable goods in this underground facility. However, it is uncertain whether this tunnel system ever existed. In any case, the Czech secret service agents who interrogated and even tortured Klein got nothing out of it. Klein was not released from prison until 1964. He died seven years later.

The story of Emil Klein and the alleged Stechowice tunnels has been known for years. However, the TV documentary provides some new information. In particular, the authors had the opportunity to see notes and drawings that Klein made during his time in prison. Klein was a good draftsman, and so he made numerous sketches that allegedly showed parts of the tunnel system and other motifs. The Czechs probably couldn’t do much with them.

Some of the notes Klein left behind are in code. The TV documentary doesn’t go into detail about these cryptograms, but at least a few are shown, and it is mentioned that the Czechs cracked them. However, I have no information about how this was done and what kind of encryption system Klein used. I also don’t know anything about the plaintext.

The following screenshots from the TV documentary show the encrypted texts:

In a blog article of mine there are more screenshots.

The excerpts shown should actually be sufficient to solve this encryption. However, to my knowledge, no one has done this yet. Considering the amount of ciphertext Klein produced and the fact that he had no cipher tools or machines at hand during his captivity, the encryption method he used should not have been particularly complicated. Most likely it was a monoalphabetic substitution (MASC).

A list

Here is a list of unsolved cryptograms from World War II. The individual entries are noted in English. The first five entries are from this article.

- Bullet cryptogram

- Rilke cryptogram

- Schleswig-Holstein telegrams

- Köhler cryptograms

- Soldier journal

- Carrier pigeon message

- Air plane radio message

- French message

- Enigma message

- Doppelkasten messages

- M-209 message

- SS radio message

- Spanish Enigma message

- Consular messages

This list is certainly not complete. In particular, there are certainly some more Enigma messages from World War II that are unsolved. Also, some of the cryptograms may have been solved by now. I hope that my readers can help me to extend and improve the list.

If you want to add a comment, you need to add it to the German version here.

Follow @KlausSchmeh

Further reading: Die Slidex: ein Low-Tech-Verschlüsselungswerkzeug aus dem Zweiten Weltkrieg

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13501820

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/763282653806483/

Letzte Kommentare